Simon de Montfort and the Birth of England’s First Parliament

Simon de Montfort rose to power during a time of significant political transition in England. In the mid-13th century, the monarchy’s power was increasingly challenged. Costly foreign wars, mounting debt, and growing resentment towards the influence of foreign courtiers and advisors marked King Henry III‘s reign. The imposition of heavy taxes and administrative errors exacerbated tensions between the king and his subjects. It was against this backdrop of dissatisfaction and unrest that Simon de Montfort emerged as a key figure.

De Montfort, a man with strong convictions about governance and reform, was a naturalized Englishman born in France. In 1265, he convened a parliament that was revolutionary for its time. Unlike the traditional councils of the king’s closest advisors, Montfort’s parliament included not only nobles and clergy but also knights and burgesses. His intention was both principled and politically expedient, but the outcome was a lasting change. Chroniclers of the time noted that “the commons were first summoned,” a seemingly innocuous but fundamentally important moment in the development of constitutional governance.

England Under Henry III

King Henry III’s rule was an era of opportunity and of challenge. Rising to the throne as a child after the chaos of his father’s reign, he succeeded to a kingdom ready for peace and stability. But, through mismanagement, poor foreign policy, and his own weaknesses, he would struggle to keep the peace, and ultimately reign for longer than any other medieval king (1216-1272). Henry’s reign was in many ways one that set the stage for the change that would follow in the next century, for the short reign of his son and the long rule of his grandson.

Cassell’s History of England – Century Edition

Henry came to the throne in 1216 when he was only nine years old, in the shadow of his father’s legacy of war and heavy taxation. In the early years of his reign, his minority government did a good job of reestablishing the peace and stability of the kingdom, leading to a period of generally harmonious rule. He inherited a kingdom still reeling from the collapse of his father’s reign, with a depleted treasury and a population of barons tired of war and taxes. He came to the throne with high hopes and an ambitious program of construction and patronage that would define his 56-year rule.

But these decades were also marked by reliance on foreign advisors, the lavish spending on Westminster Abbey and the royal palaces, and ultimately, the failures of his foreign policy and expensive military campaigns in France. His repeated efforts to regain Normandy and other lost territories in France were costly and yielded little. His expensive “royal castles” in Windsor and castles across England and Wales were a frequent source of financial drain and resentment.

These tensions were exacerbated by Henry’s favoritism towards his French relatives and Poitevin associates. The growing number of these foreigners at Henry’s court and in positions of power in the kingdom was a source of great annoyance to English barons. The demands for new taxes to finance his campaigns in Gascony and his inept foreign policy exhausted the royal treasury. Despite his vow to make his kingdom rich again, England became a debtor nation in the later years of his reign.

The final straw was Henry’s disastrous agreement with the pope to fund an expedition to place his son on the throne of Sicily, a scheme which left England deeply in debt, and many of his barons in a state of fury. In the 1250s, these decades of simmering tensions were about to coalesce into a reform movement.

Henry had, many nobles felt, trampled on the principle of governance by law that had been established with the sealing of Magna Carta half a century before by his father. Henry had repeatedly violated the spirit of this charter in his actions. He had taxed without consent and seemingly at will. The king’s charters to the towns, sheriffs, and other officials were being revoked at his whim. As the historian and chronicler Matthew Paris observed, “everyone knew the realm was being more ruled by will than by justice”.

The rising tension and growing power of the baronial opposition to the king led to calls for reform and the restoration of the “ancient liberties of England.” There was also an increasing sense that the crown needed to be bound by the rule of law and that it could not rule without the consent of its people. These ideals had been set out in Magna Carta, yet the principle of consultation, common consent, and the rule of law that these charters had established were not being realized.

The voices calling for reform and the limitation of royal power came not just from the barons, but also from the Church and the growing ranks of the towns. Reformers in England were beginning to insist that the king could not act alone and must be bound by the collective will of his subjects.

It is in this context of medieval mismanagement, frustrated barons, and idealistic reformers that Simon de Montfort would lead his rebellion, a decade of reform and the revolution that would take place in the next century.

Simon de Montfort’s Rise

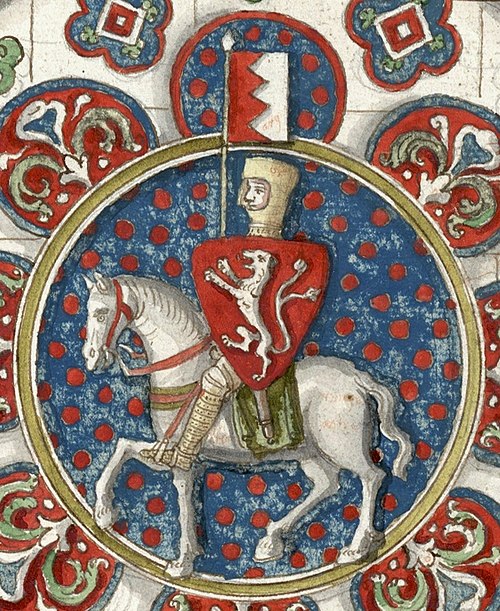

Simon de Montfort was born in France circa 1208 to a family of pious and martial reputation. His father, also named Simon, led the Albigensian Crusade in the Languedoc, a region in southern France, an act that brought both notoriety and wealth to his family. Montfort, born Simon, came to England in the 1220s to press his claim to the earldom of Leicester through his grandmother.

Though a foreigner, he found his way in the English court easily, impressing some and raising eyebrows in others at his ascension in the ranks of government. His facility with languages and diplomatic savvy lent him a place among a still-fractious baronage that could be united only by their differences between old Anglo-Saxon families and the newer nobles imported from the continent by King Henry III.

Montfort’s position at court was secured when he married Eleanor, the widowed sister of Henry III in 1238, a match that English barons much resented at the time. The relationship between Montfort and Henry was sometimes cordial, but Henry was quick to feel slighted and then resentful. He granted Montfort extensive land and commissions, but later blamed him for exercising near-autonomous control over the English holdings in Gascony to the south of the channel.

Montfort, an exacting administrator who imposed heavy taxation and conducted little local consultation, managed to alienate the local nobility and townsfolk, resulting in complaints in the English court by 1252. These private squabbles and accusations from Henry were to come to a head in the early 1250s.

Montfort’s political acumen became engaged as he saw the actual effects of mismanagement and incompetence under Henry’s rule. Taxation was on the rise, and political instability and foreign conflict were common. In this, Montfort’s pre-existing religious convictions were reinforced by his relationships with many reform-minded individuals in the Church. The idea that the king ruled by divine right to do as he pleased was percolating in the minds of some of the more powerful nobility at court, and Montfort found that he had entered into their ranks and ideals. Matthew Paris, in the margins of his notebooks, scribbled that “he spoke as one who feared God more than man”.

Montfort cultivated ties with noble and ecclesiastical reformists and became a visible part of the rising tide of criticism of royal policy. Montfort’s intentions in all of this were mixed; he was a devout man, and he was concerned with the role of the crown. However, he also understood the political opportunity in the mounting reform movement. His convictions were sincere, but self-interest also played a key role in his aims.

He sought to limit the authority of the crown by the will of the people; in this, he was as much a power-grabbing opportunist as any baron before or since. By the time the reform movement had coalesced into organized activity, Montfort was among its leaders. In the Provisions of Oxford in 1258, Montfort’s career transitioned from that of a foreign noble to a reformist leader as England found itself spiraling towards crisis.

The Road to Rebellion

After years of financial exploitation and political oppression, the English were unable to continue enduring such mistreatment at the hands of Henry III by 1258. The wealthiest and most powerful barons within the realm finally reached a point of no return. They insisted that King Henry revoke his policy of misgoverning the kingdom and force him to accept the so-called Provisions of Oxford, a set of legal documents that dramatically restructured the relationship between the king and his subjects.

The agreement placed the king under the control of a new royal council of fifteen individuals. The reform granted these men the authority to oversee the king’s actions, particularly in financial matters, and to determine the proper course of government with the consent of the realm. Simon de Montfort’s importance in the organization and implementation of the Provisions was of no small magnitude. Montfort led one of the most powerful groups of barons in the English realm, convinced that the will of the crown must be kept in check by law and the needs of the entire kingdom.

The Provisions had an enormous impact on the kingdom. England had never experienced a transformation of politics of such magnitude. At the same time, King Henry was only biding his time; the wealthy barons had finally achieved something that they had long desired. Reform had become the order of the day. The tide would soon turn once again. King Henry traveled to Rome and received a papal bull absolving him from the Provisions. The early 1260s saw the tensions in the kingdom, which had seemed to be subsiding with the reforms of 1258, flare up once more.

Henry had decided to challenge the Provisions and work against the very barons who had helped support them. The kingdom was now, as before, divided between royalists and reformers. The medieval chronicler William Rishanger would later state that “the kingdom was shaken by the contest of lords and king, each claiming right and justice.”

Simon de Montfort’s involvement in the following political turmoil was of vital importance. His personal and political differences with Henry III had steadily grown and would soon come to a head. His opposition to the king had turned into a complete defiance of royal authority. Simon de Montfort could not back down from his opposition as some of the other barons did, as he had emerged as the standard bearer of reform and the majority of the government.

Montfort’s baronial party was backed and supported by the lower clergy and townsmen, who saw the reforms in a religious sense as morally justified. It is within this context that the subsequent conflict between the king and Montfort can be considered a civil war of sorts. Known as the Second Barons’ War, the opposition to Henry III and his authority began in earnest. What would become known as the “Battle of Lewes” was the climactic turning point of the First Barons’ War.

In May 1264, the opposing forces met in Sussex at Lewes. Montfort and his forces of roughly 800 men were met by a royalist army of double their size. Montfort had planned for the attack that was about to take place on the level grounds before the battle. He had used the high ground to his advantage and took up position on a hill behind a ditch.

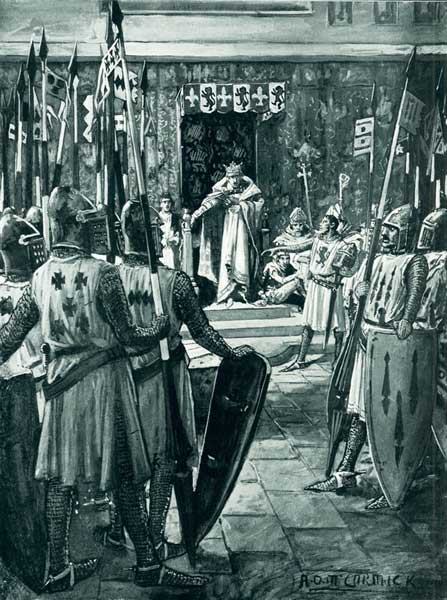

By this point, Henry and Edward both had launched a full-scale attack and, due to a lack of discipline, the royalist forces had begun to tire out. Montfort and his men routed the entire royalist army. King Henry III and his son Prince Edward (the future Edward I) were captured, and the government of England was placed into Simon de Montfort’s hands.

The victory at Lewes would have a tremendous impact on the government of England. Power was no longer being forced from the hands of the king; it was being taken. Montfort now had direct control of the government and was, therefore, in a position of political power that no other baron in England had ever been in before. It was with this in mind that Montfort’s hand would become forced by the political and social pressures at this time. The subsequent years of Montfort’s government would show if reform was compatible with stability or if the English experiment in shared rule had been a failure.

The First Parliament (1265)

The parliament that Simon de Montfort convened in January 1265 was one of several essential steps in the development of parliamentary government in England. The concept of a royal council that advised the monarch and had the authority to levy taxes was not new; earlier parliaments had included members of the nobility and the higher clergy.

However, Montfort’s parliament was significant because he also ordered the election of two knights from each shire to attend, as well as two representatives from a select number of boroughs. The members from the shires were known as “knights of the shire,” while the borough representatives were ordinary townsmen referred to as burgesses. This new parliament was different because it included elected representatives of “all the realms of the land.” Chronicler William Rishanger noted that “those who had never before been called came now at the summons of the realm.”

The need for Montfort to have a functioning government that could gain wider support for his activities, and the obvious benefit of a broader representation of the realm, were practical reasons for summoning this parliament. However, they also reflected Montfort’s acceptance that his authority, which had emerged from an act of rebellion, required legitimacy by consent of those governed, not just the victorious might of his army.

In this, his invitation to knights and burgesses to sit as commoners in the parliament was also a recognition that the welfare of the country required the input and support of those beyond the nobility. The knights represented the landowners and rural population of the shires. At the same time, the burgesses reflected the power and importance of the rapidly developing towns in England, whose merchants, craftsmen, and traders contributed taxes to the royal coffers.

The need for Montfort to have a functioning government that could gain wider support for his activities, and the obvious benefit of a broader representation of the realm, were practical reasons for summoning this parliament. However, they also reflected Montfort’s acceptance that his authority, which had emerged from an act of rebellion, required legitimacy by consent of those governed, not just the victorious might of his army.

In this, his invitation to knights and burgesses to sit as commoners in the parliament was also a recognition that the welfare of the country required the input and support of those beyond the nobility. The knights represented the landowners and rural population of the shires. At the same time, the burgesses reflected the power and importance of the rapidly developing towns in England, whose merchants, craftsmen, and traders contributed taxes to the royal coffers.

In January 1265, for the first time, commoners were included in the national affairs of the government. The extent of their role is debatable; their power was initially limited, their involvement somewhat reluctant, and their contribution largely consensual. But they were there, and, as much by accident as by design, the principle of common counsel had been established. Montfort’s shire knights and borough burgesses set a precedent that was eventually to provide a genuine representation of the “common wealth” (or welfare) of the country. This principle developed over the next century into one of the earliest identifiable examples of representative democracy in medieval Europe.

The creation of this “four estates” parliament did not last long. Montfort’s hold on the government was tenuous, and royalists and barons who had initially supported him or been forced to surrender at Lewes feared his increasing power and influence.

Fall and Death of De Montfort

The uneasy equilibrium Simon de Montfort had established in 1265 began to fracture almost as swiftly as it had been constructed. Montfort’s power, however revolutionary it may have seemed, still hinged upon the consent of his fellow magnates and the uneasy alliances he had formed. Prince Edward, who had been held hostage since the Battle of Lewes, managed to escape his captors in the spring through a ruse; he persuaded his guards to allow him a short ride for exercise, before riding away to muster the forces of loyalists.

In a display of remarkable efficiency, Edward reorganized the royalist army, capitalizing on the support of barons who were disillusioned with Montfort’s rule and the uncertainty it had brought to the kingdom.

The summer months saw the two factions position themselves for a renewed conflict. Montfort, isolated from some of his former allies and tactically outmaneuvered by Edward’s agile cavalry, found his hold on power slipping. On August 4, 1265, Montfort’s forces encountered the royal army on open ground near the market town of Evesham, in Worcestershire. The confrontation was swift and bloody. Outnumbered and encircled, Montfort allegedly realized his position was hopeless and is reported to have said to his men, “Let us commend our souls to God, for our bodies are theirs.” The subsequent engagement was less a battle and more a massacre; Montfort and many of his adherents were slain amid a downpour and thunder.

In the aftermath of the Battle of Evesham, the dismembered body of Simon de Montfort was said to have been mutilated on the battlefield, with his head and limbs carried off as trophies by the victors. Accounts of his final moments and subsequent treatment vary, but it is widely accepted that even in death, Montfort remained a polarizing figure; to his adversaries, a traitor who had dared challenge the anointed king, to his sympathizers, a reformer who attempted to place law above might. The restoration of royal authority was swift, and within months, surviving rebels were forced to capitulate and submit to the king’s mercy.

The memory of Simon de Montfort, however, proved more resilient. Amongst the more reform-minded clerics and urban dwellers, his death was imbued with a sense of martyrdom. Pilgrimages were made to his supposed burial site at Evesham Abbey, and soon tales of miracles attributed to him began to circulate. He was never formally canonized, but among those who remembered him, Montfort became a symbol of the struggle for accountability in governance, a man who sought to ensure that the crown was answerable to the law and the welfare of the realm.

Chronicles from the time offer a glimpse into the contrasting views of Montfort’s character. Chronicler Thomas Wykes called him “a man of steadfast faith who sought the kingdom’s peace,” suggesting a more noble view of his intentions. In contrast, some later accounts focus on his ambition as the root of the baronial conflict. In the post-Evesham political landscape of England, Montfort’s vision for a reformed government found new life, not through his leadership, but through the precedent set by his 1265 parliament. The notion that the king could, and indeed should, consult with his subjects before making decisions became a cornerstone of English governance, a lesson that rulers reasserting their power would be wise to remember.

Legacy and the Birth of Representation

The king had emerged victorious, but the spirit of Montfort’s ideals lingered on. In the years following Evesham, Henry III and his successors redoubled their efforts to consolidate royal power, yet they could not erase the memory of reform. The notion that government should function with the advice and consent of representatives, men who spoke for the counties and towns, took hold. The practice that Montfort had devised as a necessity of rebellion evolved into an idea of governance, one that would become central to the English political tradition.

Edward I, who took the throne in 1272, did not dismiss the notion of consultation so much as reappropriate it. His Model Parliament of 1295 included barons, clergy, knights, and burgesses, not unlike Montfort’s assembly. However, Edward formalized the system, subjecting it to the will of the crown. In his writ of summons, Edward proclaimed that “what touches all should be approved by all,” a sentiment that seemed to embody the reformers’ vision of government by consent. In this way, a balance was struck between monarchy and representation, which would form the foundation of English constitutional development.

The frequency and regularity of parliaments increased, and their functions became more formalized as instruments of taxation, legislation, and political bargaining. The participation of commoners provided towns and shires with a stake in the realm, mediating the interests of local and national governments. The medieval system was a far cry from the modern concept of democracy, yet it established the principle that the king could not act unilaterally. Representation, limited, imperfect, and often contested, had become an integral part of the political order.

The question of Montfort’s motives will no doubt continue to be a source of debate among historians, but few can doubt the impact of the assembly he called in 1265. Whether the product of idealism, strategy, or a combination of both, it would provide a framework for future generations to build upon. The chronicler William Rishanger called Montfort’s parliament “a new order of council,” one that brought together the manifold voices of the kingdom in a single chamber. In this sense, it stands as a prototype of parliamentary democracy, one in which authority was tempered by advice and consent.

The legacy of Simon de Montfort’s parliament does not lie in monuments or battles but in institutions. From the Houses of Parliament in Westminster to legislative bodies the world over, the idea that the governed should have a voice in government can trace part of its lineage to that January gathering of 1265. The monarchy had regained its power, but England’s political landscape had been forever altered. Transformed by the idea that representation, once kindled, could not be extinguished.