Celtic Pride: The Legacy of Vercingetorix

In the days when the Celtic Gallics were riven by factionalism and local patriotism, Vercingetorix stands out as a unique figure, someone who had a broad vision and the will to make it real. A member of the Arvernian aristocracy, born c. 82 BCE, he broke with tradition to create an alliance of the warlike Celtic clans to oppose Roman expansion. At the height of the Gallic Wars he became the greatest enemy that Julius Caesar ever had to face.

At a time of Roman encroachment, Vercingetorix led his resistance both as a military leader and as a symbol of defiance. In defeat he was marched through the streets of Rome and executed, but his legacy and memory have proved far more lasting. Vercingetorix is now honoured as a national hero in modern France.

Origins and Rise to Power of Vercingetorix

Vercingetorix was a noble of the Arverni tribe, a people so influential in the Celtic world that they were sometimes called kings. His father Celtillus had died young, victim to the ambitions of his peers. Celtillus had tried to lead all the Gauls, but was killed by other tribal leaders for “having dared to aspire to this great power. In the raw and ancient politics of tribal alliance and enmity, the incident left its mark on Vercingetorix. The dream of centralized power was magnetic but also perilous in a society built on fierce local independence. Vercingetorix would grow up in the mountainous area of central France during a time of rising Roman activity in Gaul.

The Roman invasions of Gaul, which Vercingetorix would come to lead the defense against, were political earthquakes. Julius Caesar first arrived in 58 BCE and began a very different sort of occupation, one that methodically exploited old tribal enmities and formed alliances to divide and conquer. Gaulish society would never be the same, as Vercingetorix and his fellow tribespeople experienced firsthand the effectiveness of Roman divide-and-conquer tactics. At the same time, the dream of unity, so tantalizing to the Gallic mind, proved so elusive and distant as the Gauls ravaged one another with jealousy and war.

52 BCE was Vercingetorix’s year to step up. Despite initial rebukes from the Arverni aristocracy who scolded him for being unduly defiant, Vercingetorix took up arms in the countryside and, with a hastily gathered army, reconquered the tribal capital at the point of the sword. But this was no ordinary coup.

As fast as he had taken power, Vercingetorix transcended his tribe to become the symbol of a Gallic national movement. “He was a man of great ability,” as Julius Caesar writes in Commentarii de Bello Gallico, “distinguished by courage and celerity in warlike enterprises, and by authority and influence over the soldiers.” In short order, he was posing not as a tribal chief or warlord but as the Gallic man of destiny.

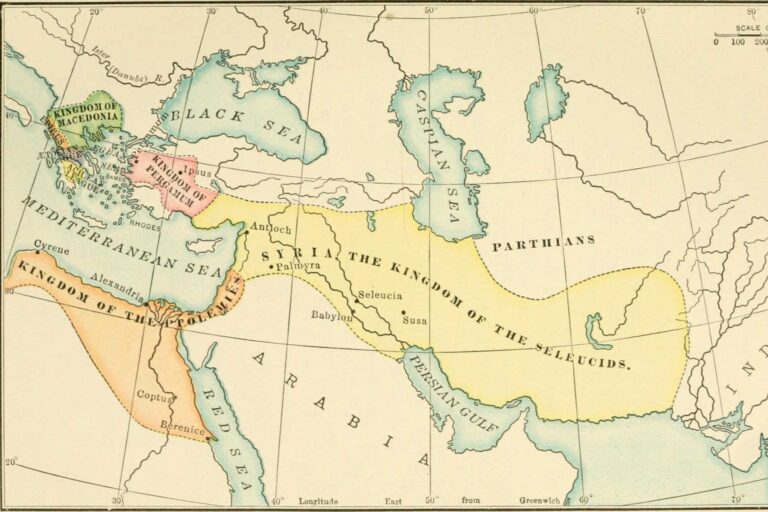

In his daring, Vercingetorix was to a large degree singular. Gaul was, in many ways, a remarkably cohesive cultural entity. Language, religion, and cultural practice were largely common across the area. But this did not naturally lead to a cohesive politics. To his credit, by a mixture of diplomatic outreach, force of arms, and sheer inspiration, Vercingetorix won the support and alliance of the three major tribes: the Bituriges, the Carnutes, and the Senones. The idea that all Gauls might rally to one cause under one man, instead of following their own individual tribal agendas, was unique in Gallic history. If only for a short while, they did.

War Against Rome

By 52 BCE, when Vercingetorix rose to prominence, Julius Caesar had been conducting military operations in Gaul for a number of years. His Commentarii de Bello Gallico (Commentaries on the Gallic War) record his campaigns and significant victories in the region. Caesar was not only expanding his empire but also his reputation, and the conquest of Gaul was a political prize for him. Vercingetorix’s revolt was to become the most considerable resistance Caesar had encountered so far. Unlike other tribal chieftains, Vercingetorix was a young nobleman of the Arverni who commanded the respect and support of a coalition of Gallic tribes.

Vercingetorix’s tactics were mainly guerrilla warfare. He avoided open battle and instead resorted to ambushes, raids, and the scorched-earth policy. “He decided to wage war not by engaging in battle, but by devastating the countryside,” Caesar wrote in his accounts of his adversary. He burnt the villages and crops, destroyed food supplies, and evacuated the civilians to make it hard for Caesar’s legions to live off the land. This not only weakened the Roman forces but also demoralized them as they marched through the deserted and charred landscapes of Gaul.

Another critical aspect of Vercingetorix’s strategy was the use of psychological warfare. He was well aware of the Roman psyche and was able to play on it. The harassment of their supply lines, the hit-and-run tactics of his cavalry, and the constant threat of surprise attacks frustrated the Roman soldiers, who were unused to a war waged on unfamiliar and unpredictable terrain by an elusive enemy. Vercingetorix was a master of using the element of speed and surprise to his advantage, primarily through the deployment of cavalry, including the fearsome Gallic cavalry. This harassment on all fronts forced Caesar to divide his forces.

The Battle of Gergovia was Vercingetorix’s most tremendous success in the field. The young chieftain cleverly used the steep hills around the Arverni capital to repulse the Roman attack. The Romans were forced to retreat in disorder, suffering significant casualties in the process. This battle was one of the few instances where Caesar’s forces were defeated, and his near-certain victory turned into humiliation. The defeat of the Roman legions at Gergovia galvanized support for Vercingetorix, with many more tribes joining the revolt. The Roman forces’ unassailable nature had been punctured, and the hope of a free Gaul seemed possible once more.

Despite these successes, the war took a heavy toll. Roman forces were regrouping and receiving reinforcements from Italy. Vercingetorix also had to contend with the fractious and shifting loyalties of the various Gallic tribes. Caesar was also a shrewd politician and managed to play one tribe against another. The use of scorched-earth tactics also had a significant cost on civilians in the Gallic territories, with many at risk of starvation or displacement from their homes.

As the Romans regrouped, Caesar forced Vercingetorix into a more defensive stance, eventually leading him to fortify himself at Alesia. This would become the stage for Vercingetorix’s final stand, where he was ultimately defeated and surrendered to Caesar. Even as he retreated, Vercingetorix continued to use his knowledge of the land and his guerrilla tactics to cause as much trouble for the Romans as possible.

Even in defeat, the war was a significant turning point for Gaul. Vercingetorix’s stand became a symbol of resistance against Roman imperialism. He had managed to unite disparate tribal uprisings into a well-organized front against the might of Rome. Although his revolt ultimately failed, he gave Gaul its best chance at independence, creating a legend that would be remembered and revered for generations to come.

Siege and Surrender at Alesia

The hilltop city of Alesia, fortified and nestled in what is now Burgundy, was naturally defensible. Vercingetorix, with his back to the wall, hoped the site would buy time for a relief force to come. The Gaulish leader brought his troops – Caesar’s estimates place them at about 80,000 – along with thousands of non-combatants. But it would test his leadership and his people’s endurance.

Julius Caesar understood the importance of the battle and built a double ring of fortifications around Alesia. The inner line held the Gauls, while the outer ring of defenses would keep a relief army, which Caesar expected, at bay. Caesar’s siege works were miles long and incorporated ditches, ramparts, watchtowers, and traps. Inside Alesia, Vercingetorix kept up morale and order, despite dwindling supplies and a crushing siege. He exhorted his warriors to hold until the relief force arrived, organizing sorties and sabotaging the Roman lines. He also coordinated signals with the relief force, hoping to time a synchronized, two-front assault on Caesar’s legions.

The relief army, likely more than 200,000 strong, did indeed come, and a general assault was ordered. For several days, the battle was fought on two fronts. Inside the city, Vercingetorix led hopeless charges. Outside, Gallic reinforcements attacked the Roman outer defenses. But the legions were too disciplined, and Roman engineering too strong. The relief force was defeated, and Alesia was effectively cut off and starved. Vercingetorix, facing certain death for himself and his people, surrendered.

Ancient accounts, particularly Caesar’s Commentaries, provide a more dramatic account of the surrender. Legend says Vercingetorix donned his best armor and took his horse. He then rode through the Roman lines to Caesar, a king among captors. In front of Caesar, he dismounted, removed his weapons, and bowed his head in silence. He said nothing, but the gesture was eloquent: the proud leader of a rebellious people, who defied Rome with words and swords, met his conqueror with a show of dignity.

Imprisonment and Execution

Taken alive by Roman soldiers after Alesia’s surrender, Vercingetorix was forced to walk in chains all the way to Rome, to the victorious Caesar. He was later transferred to Caesar’s villa at Alba, where he was bound in iron and tortured by the soldiers. The Gallic chief was often paraded as a war trophy through Roman villages on his way to Rome.

He was finally sent to Rome as a prisoner of war, serving as Caesar’s trophy, and was displayed in the most extravagant triumph of all time. In the city, the king was confined in a Roman jail cell but not condemned to death. This was a common practice as Caesar and the Romans often spared their greatest captives, as they could only be paraded in a triumph, the massive military victory celebration held once a Roman general had won his wars and returned to Rome.

Six years later, as the prisoner in the damp and dark Tullianum (Roman prison), Vercingetorix, most likely bound in iron and slowly starved to death (very slowly), was “alive but dead”. However, Roman sources are silent regarding Vercingetorix’ treatment in the Tullianum. Of his almost seven years of Roman captivity, we know nothing for sure except for his ignominious end. He was in effect alive but dead: he was tortured and a living corpse. Waiting for Caesar’s triumph, he did not die because Romans spared the greatest of the vanquished to exhibit them for maximum glory and propaganda effect at the eventual victory celebration.

The actual murder of the Gallic Chief would occur in a final, public humiliation: in 46 BCE, as Caesar celebrated his four-day triumph in Rome, the chief had to walk in chains before the cheering crowds. The ancient sources uniformly report that during his parade, Vercingetorix was mocked, hissed at, and spat upon by the crowd, yet pitied as the embodiment of a brave enemy. On the third day, he was taken to a dark, empty cell and there strangled to death, per Roman practice. There is no mention of a trial or formal execution; instead, Vercingetorix was summarily executed by strangulation.

Vercingetorix’s death marked the final extinguishment of Gallic national identity. Although some smaller, isolated rebellions broke out over the next century, no new Gallic leader would have the same charisma or unifying influence as Vercingetorix. After Vercingetorix, the dream of a free Gaul was over, as Caesar had total control over the area, and his influence there was total and complete.

Vercingetorix’s reputation has continued to grow since his death, however. Vercingetorix led the last major attempt by Gauls to drive the Romans out of what is now France, and this is what made him immortal. He died a Roman prisoner, a victim, not a condemned man, and according to the legends, he was strangled to death by the Romans. Vercingetorix died a hero to the French. By “slowing” the Roman march, Vercingetorix would become a later French nationalist hero. In death, the Frenchman Vercingetorix would live as a memory that his people would never forget.

Cultural Symbolism and Legacy in Ancient and Modern History

Vercingetorix first appears in our world by the hand of his conqueror, Julius Caesar. The great emperor, in his chronicle Commentarii de Bello Gallico, painted him as “a man of great ability, whose influence extended far and wide.” Caesar wrote it, of course, to aggrandize his own military and political successes, and it effectively became propaganda for the Roman state. But it also made Caesar’s greatest enemy an immortal in literature, and Vercingetorix became the only Gallic leader to ever inspire his people to unite against a familiar foe.

From Caesar, Vercingetorix drops off the map for nearly two millennia. Rome crushes Gaul under its feet, and the Middle Ages only deepen the Gallic chieftain’s obscurity. He is not a part of history so much as an asterisk. It is not until the heady times of French nationalism in the 19th century that the memory of Vercingetorix returns. Humiliated by Prussian defeat in 1871, France’s ruling class is eager for symbols of national unity and to reassert French culture’s claim as the legitimate successor to Rome. Vercingetorix, who united the fractious tribes of Gaul to oppose Julius Caesar’s invasion of his homeland, was the perfect candidate.

Napoleon III, the nephew of the first, cast himself as the unifier of French history and successfully appropriated the Gaulish warlord into the national story. The emperor personally supervised archaeological digs at Alise-Sainte-Reine, the site of Alesia, and a statue of Vercingetorix leading his Gallic army against the Romans was erected there in 1865. The inscription at the statue’s base reads “Gaul united, forming a single nation, animated by the same spirit, can defy the universe.” This reimagined Vercingetorix not as a warrior brought low, but as the unifier of the Gauls and the first true French national.

This new myth of Vercingetorix came to represent Celtic Gaul and, by extension, all things proudly Gallic, subversive, and independent. A national treasure, he was imbued with attributes and values valued by 19th-century France. The sculptor, therefore, made his statue of Vercingetorix embody the romantic ideal, a noble barbarian whose very nature stood against Rome and all it represented. The image of Vercingetorix at Alise spread far beyond Burgundy. He appeared in poems, novels, and histories and even a scene in one of Georges Méliès’ proto-cinematic peepshows.

Vercingetorix is now entirely a part of France’s modern history. He features in popular fiction and appears in French classrooms as a local legend from a long-vanished age. The statue of him in Burgundy is a place of pilgrimage. French schoolchildren know his story from a young age as part of their national history, and he has come to occupy the role of a cultural war hero. He can be found in cartoons and video games, and his name is frequently invoked in defense of regional or cultural pride against various interlocutors. Today, the legend of Vercingetorix continues, and he remains an emblem of France and French culture.