Easter Rising of 1916 and the Birth of Irish Independence

The Easter Rising of 1916 was an armed insurrection by Irish nationalists against British rule. Fewer than 2,000 Volunteers took part, rising up in Dublin for six days in April 1916. Although they managed to take several strategic locations around Dublin city center and issued a Proclamation of the Irish Republic from the General Post Office, from a military perspective, nothing about the Rising was successful. It was put down within a week by numerically and technologically superior British forces. Central Dublin was burned and wrecked beyond recognition, while rebels were seen by many observers as wasting the lives of civilians for what amounted to defeat.

The reaction towards the rebels was initially condemnation. They had put civilians at risk, interrupted business, and seemed morally insane for striking at Britain while she was at war. In that sense, the Rising looked like defeat indeed. But then the executions began. Suddenly, defeat became martyrdom, and the Rising took on a new significance. “The old heart of the earth needed to be warmed with the red wine of the battlefield,” wrote Patrick Pearse. These famous words now took on new meaning, as the soul of Ireland seemed to awaken from the center of Dublin. Anger turned to sympathy and, slowly but surely, the moral arithmetic of Ireland’s struggle began to change.

That is why the Easter Rising mattered. It mattered because after that day, nationalism shifted from constitutional agitation within Ireland to outright separation. In such a short space of time, Ireland went from tolerating those who protested against British rule to cheering on those who were executed for it. Many now define their lives by the period before and after the Easter Rising. That is its legacy and why it still matters 100 years later.

Ireland Under British Rule Before 1916

The Easter Rising did not happen in isolation, nor did its participants spring up from nowhere. Many of the conditions for rebellion were put in place over a century before the Rising itself. The Act of Union of 1801 abolished the Irish Parliament, and Ireland was directly ruled by Great Britain. Although Ireland now had MPs in London, parliamentary power now resided in Westminster. As a result, Ireland was governed by a Parliament many miles away, where their interests were frequently overlooked. In later years, nationalists would argue that Ireland had been shackled into Union, with no true control over domestic affairs. They argued Ireland had been reduced to a timid province of the British state.

The dominance of the landed classes became the touchstone of daily life’s grievances. Most Irish farmers were tenant farmers paying rent to an absentee landlord. Rent prices were high and always increasing, causing feelings of insecurity. The Land League and others called for fair rents, fixity of tenure, and free sale. Irish politics and the land question became inseparable. There were land acts over the following decades, which alleviated the problem but did not address the central issue of control. For many families across Ireland, rule by Britain was linked with poverty, eviction, and intimidation.

Home Rule became the other main goal of Irish politics. Groups like the Irish Parliamentary Party campaigned for Ireland to have a limited form of self-government within the UK. Leaders like Charles Stewart Parnell hoped they could win back Irish control through constitutional means. Home Rule bills were passed by the House of Commons but were then kicked into long committees, defeated, or watered down by amendments. Nationalists across Ireland were becoming increasingly despondent with the process. Some Irish nationalists began to doubt whether reform would ever be possible under British rule.

World War I was the catalyst for change. The Home Rule bill finally passed in 1914, but was suspended for the duration of the war. Irishmen were asked to fight for the British Empire and would be rewarded with Home Rule after the war. Opponents now considered the bill to have been betrayed. Months turned into years, and the promise of reform was never delivered. “Ireland’s reward for loyalty”, one Irish nationalist later wrote, “was postponement.” Dissent in Ireland grew as hundreds of thousands of Irishmen joined the British Army and died for a cause that forgot them.

One final development changed the nature of Ireland. During this period, there was a resurgence of native Irish culture. The Gaelic League began to promote the Irish language and Irish games such as hurling and Gaelic football. Many artists and poets also began to celebrate Ireland’s unique history and distance themselves from Britain. The cultural revival was not republican, but it did instil pride in the Irish and taught them their history.

In 1916, Ireland was a powder keg of political stalemate and remembered wrongs. Constitutional politicians had failed to achieve anything for Ireland. The population was poor under British rule, and a new generation was growing up with knowledge of their native culture. By the early 1910s, a new generation of republicans began to argue that Ireland would never be free until they took action. As a direct result of British rule in Ireland, people had become detached from the Constitution and were ready for rebellion.

Europe at War and an Opportunity for Revolt

In August 1914, the First World War began. Britain entered the war on a massive scale: millions of troops were deployed to the Western Front, and full effort was put into total war. Ireland was drawn into the crisis despite London’s inability to deal adequately with Irish political issues. Ireland was still administered from London, and during the War, Irish issues were put on hold. The War further entrenched the idea that when push came to shove, the Empire would always put Britain first. For others, Britain’s willingness to enter into a great war showed nationalists that British might was not infinite, nor was Ireland its primary concern anymore.

Life in Ireland would never be the same after the outbreak of war. Recruitment, censorship, and the introduction of wartime laws further extended British control of Ireland (Home Rule had still to be implemented). As life went on, supplies became harder to come by, and prices rose. News of casualties reached communities across Ireland. Ireland was being asked to contribute to a war effort for an empire that seemed happy to put Home Rule on hold indefinitely. It was a bitter pill to swallow for those who had been told that cooperation with Britain would yield meaningful results after the war.

Support for taking part in the war was split fairly quickly in Ireland. John Redmond and the IPP called for Irishmen to enlist and do their bit. In return for their service, Ireland would be rewarded with self-government after the war. Many, numbering into the tens of thousands, obliged and joined the colors. Others refused point-blank to entertain the idea of fighting for the British Empire while their country remained under British rule. One detractor of Redmond asked the obvious question: if Irishmen were to die for the liberty of Belgium, why should Ireland remain unfree?

The divide grew with time. There were those who were happy to fight for Britain and those who wanted Irish volunteers to keep their military efforts at home. The longer the war went on, the more untenable constitutional nationalism became. Promises of reform were years away, but deaths were happening now. For young activists and radicals, there was no time for patience.

Radicals had a different take on the war. Germany and Britain’s other adversaries suddenly became Ireland’s friends. “England’s difficulty is Ireland’s opportunity” became a popular saying once more. If Britain was busy dying in France and Flanders, then Ireland should attack at Britain’s weakest point: at home. By staging a rebellion during this global conflict, nationalists could free Ireland from imperial rule and internationalize the Irish question.

By 1916, the idea of rebellion had become firmly entrenched in the minds of a small group of nationalists. They knew that their chances of winning were slim, but they felt that timing was everything. WWI had created a window of opportunity, and it was their duty to take what they could from it. To them, if they didn’t act when the chance presented itself, then Irish republicanism would wither away into nothing.

Planning the Easter Rising

Secrecy, discipline, and long memory defined the planning for the Easter Rising. At the center of events was the Irish Republican Brotherhood. The IRB was an underground society dedicated to the overthrow of British rule by armed force. It existed in small cells that kept a low profile. Operating quietly within larger nationalist organizations, IRB leaders came to believe that Ireland’s failure was the result of excessive political openness. As one member recalled, their job was to simply “keep alive the physical-force tradition” until the country was ready.

They decided that the country was ready in 1916. As the First World War dragged on, IRB leaders began planning a rebellion to strike while Britain was preoccupied with the war. Plans were intentionally broad to allow for maximum secrecy. Arms were procured from Germany, training was stepped up, and loyalists were stockpiled in positions of leadership within Ireland. It wasn’t necessary to plan how to win a war. It was only necessary to plan an event powerful enough to win the war of ideas.

One organization that was central to planning but difficult to control was the Irish Volunteers. The Volunteers were founded in 1913 with the express purpose of defending Irish rights by force if necessary. By 1916, they were the largest Irish nationalist organization with several thousand members. But inside the Volunteer movement, only a few leaders knew of the IRB plan, and those few were told only what they needed to know. Orders trickled through the hierarchy without explanation. This secrecy would come back to haunt them, but for now the planners believed that surprise was more important than consistency and symbolism more important than logistics.

By their side were the Irish Citizen Army. The Citizen Army was a small group formed ten years earlier to protect strikers and workers from police brutality. They would number only around 200 by 1916 and were led by James Connolly. Connolly was a socialist whose views greatly influenced the Rising. He believed that Irish independence would be meaningless without workers’ rights. “The cause of labor is the cause of Ireland,” he proclaimed. In Connolly’s eyes, a republic would be hypocritical if it replaced the British ruling class with an Irish one without solving the problem of equality.

Of course, Connolly was only one man. The opinions of Patrick Pearse and Tom Clarke also loomed large over the planning. Pearse argued that rebellion was a virtue in itself and that dying for Ireland made the nation itself worthy of life. Clarke had spent years in jail in the United States and brought with him the Fenian traditions of old. Each leader brought their own unique mixture of romanticism, republicanism, and political pragmatism to form a consensus.

Plans went wrong. Shipments were intercepted, countermanded orders were given, and support outside Dublin was questionable at best. The leaders knew this. But they also knew that there would never be a “perfect” time for an uprising. If something radical were to be done to shake Ireland out of her complacency, it would have to be now. As Pearse put it years later, “We seem to have lost faith in our destiny.” The planning of the Easter Rising was an attempt to correct that failure.

Easter Week: The Rising Unfolds (April 1916)

On Monday, April 24th, the rebels struck. Armed with whatever weapons they could find, groups of Irish Volunteers and Irish Citizen Army members captured strategic locations throughout Dublin City. One building after another was taken, their use selected for either symbolic or strategic importance. The General Post Office (GPO) on Sackville Street was the most significant position seized that day and quickly became the rebels’ command center. Additional key buildings included the Four Courts, Jacob’s Factory, Boland’s Mill, and St. Stephen’s Green. Citizens watched in bewilderment as the Volunteers marched down the streets with flags and weapons.

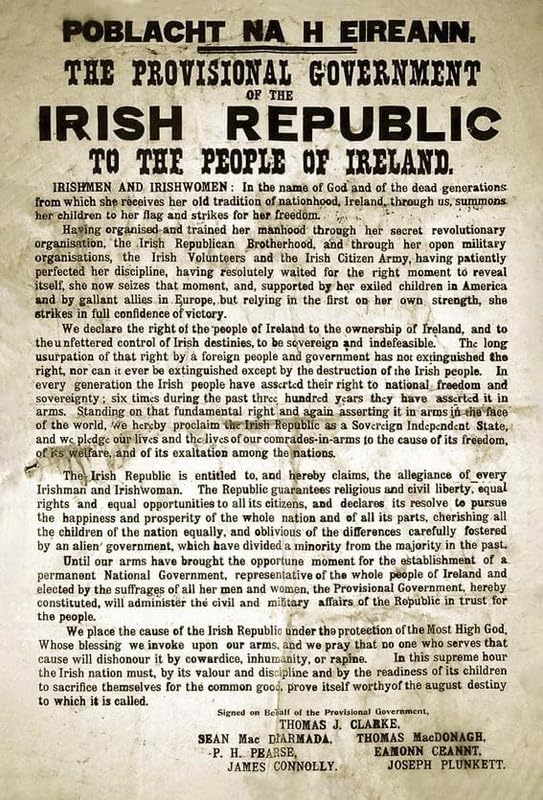

Patrick Pearse stood outside the GPO with a copy of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic in hand. He read the proclamation aloud to the small crowd that had gathered around him, declaring Ireland to be a sovereign nation in which all citizens could expect civil and religious liberty, equal rights and equal opportunity, and universal suffrage. Most of those who listened did not understand what was happening. Some shouted angrily and questioned Pearse’s actions; others simply stared blankly. For his part, Pearse did not seem to notice or care. A republic had been proclaimed in the heart of the British Empire.

Rebels stationed in the occupied buildings prepared for the British backlash that was sure to come. Barricades were constructed, windows boarded up, and communication established between the various positions when possible. While spirits were high among the rebels, they were woefully unprepared to sustain a lengthy battle against British forces. They lacked ammunition, manpower was limited, and communication between the various outposts was spotty at best. Few were comforted by these facts. For many of the rebels who fought that week, simply being there felt historic.

British troops were slow to respond, their plans disrupted by shock and indecision. But within days, troop transports arrived from Britain and the surrounding counties. Martial law was declared, and soldiers with artillery and machine guns poured into Dublin. Rather than storm the republican positions, British commanders decided to pound each location from long range with heavy artillery and machine gun fire. At once, the city changed. Dublin’s city center transformed from a bustling shopping district to a war zone.

Street by street, house by house, rebels would fight for their positions throughout Easter Week. Fighting broke out at close range, bullets cracked around corners and from behind thin barricades. The government forces brought rifles, machine guns, and artillery. Rebels and citizens caught in the crossfire sought safety wherever they could find it. Fires quickly spread throughout the city center as buildings were shelled and sniper teams engaged in fighting across rooftops. According to one reporter, the city “began to look like a place which had been visited by an earthquake.”

However, several positions, including the GPO, quickly came under intense artillery fire. Patrick Pearse’s Headquarters became clouded by smoke and debris. Inside, volunteers were forced to contend with dwindling food and warmth, and with each new casualty who rolled into the emergency hospital. Remarkably, however, orders continued to flow from headquarters. According to Pearse afterwards, the mood inside the building was lethargic but determined. Everyone inside the GPO believed that, no matter what happened, they would not surrender until it was absolutely clear they could no longer fight.

Less dramatically but with just as poor results, fire was opened up on other rebel posts throughout the city. Some held out for longer than expected, while others were attacked and quickly subdued by government troops. Numerous acts of miscommunication kept cities outside Dublin from joining the rebels, essentially leaving the capital city to rise alone. Government forces began moving through the city block by block, cutting off potential escape routes and supply lines. It wasn’t long before the rebels realized they were completely outnumbered and outgunned.

By the weekend, the rebels knew it was over. Bodies lined the streets, and more civilians were hurt than ever before. Leaders of the Easter Rising met to decide their next course of action. On Saturday, it was decided that Pearse would call for a general surrender. All fighting would cease, and Easter Week came to a close. The leaders of the rebellion knew that they had been defeated, but Ireland would never be the same again.

Collapse of the Rising and Immediate Aftermath

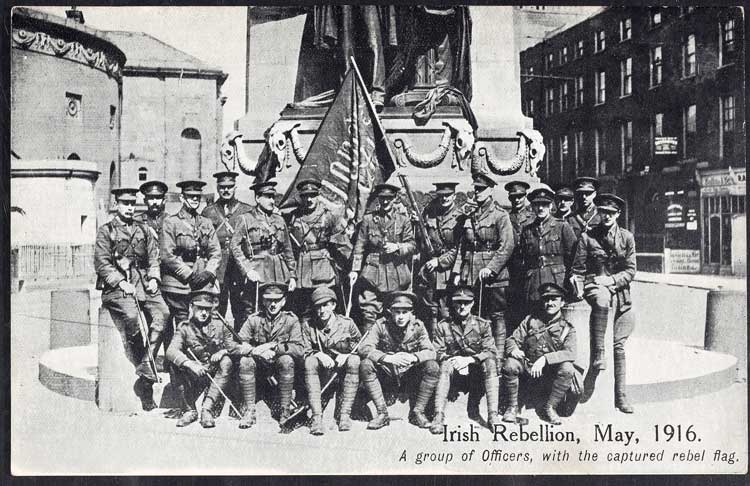

It would last six days before the Rising became unwinnable. Positions were cut off, food and ammunition were low, and British troops occupied most of Dublin city center. On Saturday, April 29, 1916, Pearse issued a notice of unconditional surrender, later saying that it was necessary to “save further loss of life”. Rebels assembled at Moore Street and formally surrendered the city to British forces.

Dublin had paid a heavy physical toll for the six days of fighting. Most of the area had suffered under British artillery bombardment and shelling. Many streets in the city center lie in ruins. Buildings were destroyed or burnt out, leaving thousands homeless. An official enquiry into civilian casualties would find that hundreds had been killed or wounded in Dublin city. Almost all casualties were deemed unavoidable accidents caused by close-quarters urban warfare.

Public perception of the Rising was colored by civilian loss. Thousands mourned their dead as citizens struggled with the aftermath. Dublin was quiet, but unrestful. Shops were looted, and food prices soared as the city began to rebuild. Anti-rebel sentiment seemed common, and it was easy to blame the rebels for the destruction in Dublin city. Civilians began to write off the rebellion as senseless. One citizen remembered that at the time Dublin city felt “sacrificed for a cause that the majority of the people did not understand”.

British officials wasted little time suppressing further dissent. Martial law was enacted, and thousands across Ireland were arrested. Rebel prisoners were marched through Dublin to their arrest points, harassed by jeering crowds. British newspapers depicted the rebels as callow troublemakers whose actions were detrimental to the war effort. There was little sympathy from the public for events at Easter Week.

Similar reactions were seen outside Dublin city. As news spread nationally, feelings towards the rebels were mixed but often negative. Families whose sons were fighting with the British Army in Europe saw the rebellion as treacherous. Constitutional nationalists criticized the Easter Rising for derailing Home Rule when it was closest to being achieved. To many across Ireland, it seemed as if the rebels had little understanding of public sentiment.

British reaction to the rebellion continued to be morale-crushing events for prisoners. Hundreds of suspected rebels and civilians were rounded up and shipped off to prisons and detention centers in Britain. Some detainees had not even been involved with the Rising. Detention conditions were tough, and many families waited nervously for news of their relatives. After six days of battle, the events of Easter Week seemed pyrrhic at best.

However, behind closed doors, public opinion was starting to turn. Angry and exhausted though many were at surrender, all of Dublin city waited to find out what would happen next. With the fighting over, attention turned to the Rebel leadership. In the days after Easter Monday, not during, did the Rising begin to change opinions.

Executions and the Shift in Public Opinion

The British wasted little time dealing with the aftermath of the surrender. Between May 3rd and May 12th, fifteen of the leaders of Easter Week were executed by firing squad at Kilmainham Gaol. Trials took place behind closed doors and sometimes lasted mere minutes. Executions were scheduled before dawn so civilians would never see them. At first, the executions received little outcry. Most Irish wanted nothing more than to forget that the rebellion ever took place. To them, it had been a foolish gambit that caused twenty-six needless deaths in Dublin city.

The mood in Ireland shifted as executions continued. The relentlessness of deaths became numbing to the population. Civilians heard rumors that injured insurgents were carried out on stretchers to be shot. James Connolly was reported to have been tied to a chair because he refused to sit down when he was shot for being in a wheelchair from his wounds. Rumors like this upset the civilians who were originally glad the executions were taking place.

Patrick Pearse had anticipated this backlash when he wrote, “the fools, the fools, the fools—they have left us our Fenian dead.” In one sense, they had left Pearse and his companions Fenian dead but transformed through British execution into martyrs for their cause. From that point on, the executions evoked sympathy rather than animosity from the public. Funeral masses were populated with mourners. Prisoners recently released from prison came home to cheering families. Families who just a week prior wanted nothing more than to distance themselves from the shame their sons and brothers caused their country.

Even those who only sought Home Rule sympathized with the victims and their families. Those who had never given Republicanism a second thought now questioned Britain’s sense and sensibilities. British leaders quickly realized their error. Executions were suspended, but the damage was done. Instead of crushing rebellion, the government legalized it in the court of public opinion. The Easter Rising would no longer be remembered for the chaos it unleashed upon Dublin city but for how many of its leaders were killed after it ended. Civilians found violence against a surrendering enemy harder to support than violence against the enemy itself.

The morality of Irish independence had been tipped in favor of the rebels. The British Empire had spent weeks bogged down in battle before deciding to cut its losses and treat the rebels as criminals. Ireland began to see, for the first time, the fight for independence not as the revolutionaries wanted, but as a cause worth dying for. “They have made rebels where there were none before,” one newspaper wrote of the executions. Support for Irish independence became easier to oppose than to adopt.

From Rising to Revolution, 1917–1919

Irish politics quickly swung against compromise after January 1916. Sympathy became political capital as survivors became voters. Sinn Féin was a marginal party before the rebellion, but became the focus of nationalist frustration and aspirations. The party did not organize the Easter Rising but inherited its mantle. Its straightforward republican message appealed to voters sick of equivocation.

This shift became apparent at the by-elections held between 1917 and 1918. In one such contest, Sinn Féin’s victory was so decisive that two men declared themselves elected. These were not mere gestures of defiance. Voters were rejecting constitutional nationalism in favor of opposition to the system itself. Parties such as Sinn Féin promised to end Home Rule by defying it.

The party’s success culminated at the 1918 general election. Sinn Féin won the overwhelming majority of Irish seats. The IPP had by this point collapsed as voters turned to republicanism. Constitutional nationalism had been a dominant force in Irish politics for generations. It unraveled in little more than a year thanks to the memories of 1916.

The Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) was left scrambling to explain itself. IPP MPs had encouraged Irish voters to support the war and had condemned the rebels. In hindsight, these reactions now seem modest. Cooperation with Westminster seemed naïve by comparison with the rebels. The executions alienated former supporters, undermining whatever trust in British justice remained.

Sinn Féin MPs did not take their seats at Westminster. Instead, they gathered in Dublin and established a parliament. Proclaimed on January 21, 1919, Dáil Éireann became the voice of Irish nationalism. Its legality rested neither on parliamentary precedent nor constitutional necessity. Instead, this parliament claimed its authority from the Irish people themselves.

The declaration of independence followed shortly thereafter. Courts, local councils, and government departments were established beyond British reach. The principles of the Rising were used to create a functioning political reality. Independence could be demanded any day, but had been achieved once work began on Monday, 22 April.

Emerging leaders like Éamon de Valera symbolized the fusion of republicanism and political success. The rebels’ sacrifices became intertwined with newfound democratic approval. Republicanism went mainstream. Its symbols and victories married together into something more potent.

The shift in political allegiances was arguably the most important legacy of the Rising. Sympathy turned people against the executions. Elections turned public feeling into political consequence. Because of the 1916 Easter Rising, Irish independence became simply a matter of time.

War of Independence and the Break with Britain

January 1919 saw the start of an armed campaign that would develop into the War of Independence. However, it would not be fought like a conventional war. Small mobile units engaged in ambushes, raids, and acts of sabotage against police and military forces. It was designed less to defeat Britain militarily than to make Irish governance impossible. It was the lesson of 1916 applied to different tactics: symbolism might light the flame of nationalism, but it would take constant pressure to effect change.

The Irish Republican Army became the primary fighting force. Recruited mostly from the ranks of former Volunteers, they depended on the initiative of local units supported by an Irish population. Intelligence became as useful a weapon as bullets under leaders like Michael Collins. Collins once said that for every intelligence operation, “You must be able to strike and then you must be able to melt away.” Regular ambushes inflicted constant harassment on British forces, wearing down their dominance of the countryside.

To break the rebels, Britain increased its presence with specially recruited troops known as the Black and Tans and the Auxiliary Division. Many British civilians and troops left Ireland out of fear. Burning towns and implementing curfews and shoot-to-kill policies alienated much of the public. Far from crushing the rebellion, British policy created martyrs and pushed many towards republicanism.

By mid-1921, neither side was close to achieving its goals. Britain was facing mounting casualties, expense, and international condemnation. The IRA was outnumbered and facing shortages of its own. In July, both sides declared a truce, leaving the path open for negotiations. Negotiations took place in London between an Irish delegation demanding independence and the British government, which was concerned with maintaining the integrity of the Empire. The threat of a return to war loomed over every meeting.

On December 6th, 1921, the two sides signed the Anglo-Irish Treaty. This established the Irish Free State as self-governing in domestic affairs and ended the War of Independence. However, Irish delegates were required to swear an oath of loyalty to the king. The treaty also recognized the partition of Ireland, and six northern counties remained within the United Kingdom. The Free State was greeted with jubilation in many areas but hatred in others. To some, it was a stepping stone to full independence; to others, it was seen as a betrayal of the 1916 Republic.

Partition tore the island of Ireland apart. In the predominantly Protestant and unionist north, residents opted to remain part of the UK. Ireland would never be the same again. Politics, people, and families were now divided by more than an ocean. While independence had been secured for the majority of Ireland, the island itself was now partitioned. Conflict and questions of identity surrounding this decision would torment the nation for generations to come.

In December 1922, the Irish Free State officially began operations. Now there was an Irish parliament, an Irish court system, and an Irish army. Ireland was no longer governed by British overlords. Of course, it wasn’t full independence, but it was more than most believed possible before 1916. Ireland had gone from unthinkable defiance to British withdrawal in only six years. That change can be traced back to a single moment: the Easter Rising of 1916.

The Easter Rising’s Long-Term Legacy

Symbols turned into memory; memory became tradition. The leaders of the Rising were canny politicians who knew the value of symbols; many also had experienced the stirring evocation of tradition in language classes. Few expected the Rising to succeed: its victory was in propaganda. The Proclamation became part of the school curriculum and was displayed at commemorations. Irish identity had been fought for, bargained for, and finally won through democratic means. But in 1916, it was won through rhetoric: Ireland was defined by the concepts of national sovereignty, blood sacrifice, and self-determination, as enshrined in the Proclamation. It created a national myth that could unite people through time by merging past, language, and politics.

Memorialization became an essential factor in how Ireland defined itself. Speeches and debates; parades and concerts, became annual rituals to remember 1916. That commemorations sometimes became partisan or aggressive was a reminder that conflict over Irish independence was unresolved, but also evidence that remembering the Rising was something the Irish people deemed important to do. Pearse’s conception of nation-building – that nations must be ‘established…by blood sacrifice’ – was contentious, but impactful. Ireland’s thinking about independence was shaped by the Easter Rising.

Independence was also influenced by the Easter Rising beyond Ireland. Independence movements in India, Kenya, and the Middle East would look to 1916 as inspiration for their own campaigns against the British Empire. The Easter Rising symbolized to colonial territories that even the greatest power on Earth could be challenged by a violent uprising. Moreover, if the rebels’ moral authority outweighed that of the state in 1916, perhaps there was hope for other independence movements facing similar overwhelming odds.

That is something the leaders of the Easter Rising were well aware of. The leaders cast the rebellion in international terms, distancing Ireland from the European powers and instead seeing Ireland’s future as lying with ‘freedom loving nations across the world’. The Easter Rising thus became an integral part of Ireland’s international identity in diplomatic and political terms after independence. This global view of the Rising’s significance helps explain its continued legacy at home.

It also left Ireland with questions. The valorization of the sacrifice of the men of 1916 contrasted with the violence of the Irish Civil War and led some to question the partition of Ireland and, later still, the violence in Northern Ireland. For some, the celebration of 1916 bordered on glorification of violence. To counter that the result of the Rising was independence – something that may have never been achieved had it not been for the Events of Easter Week 1916 – was to argue that its legacy was still unfolding.

The Easter Rising impacted Irish culture in books, songs, and poetry. The events of Easter Week were constantly revisited in years afterwards to critique or praise what had happened. ‘A terrible beauty is born, wrote William Butler Yeats of the Rising. Two lines from his poem epitomize the lasting legacy of 1916; the questions they raise are still being asked about the Rising today.

Why did the 1916 Easter Rising matter? It mattered because the rebels chose to challenge the authority of the United Kingdom. It mattered because ordinary Irish people chose to continue engaging with that challenge year on year. The Rising matters because it reminds us that politics is about changing people’s minds before it becomes about changing institutions.

Failure That Birthed a Nation

By any military standard, the Easter Rising was a disaster. Few in number, lightly armed and poorly coordinated, they were defeated after a week of fighting. But these are not the standards by which history measures events like these. Easter week of 1916 proved that there was no going back to the status quo for Ireland or Britain. The Union would have to change because of what happened in Dublin. Not what was achieved on the streets, but what ideas were set free. The Rising itself “failed in action but succeeded in awakening,” and Ireland would never be politically the same in just one generation’s time.

The events of 1916 changed Ireland’s future by changing Irish minds. Before the Rising the people remained loyal, because independence was simply a political dream. But when the rebel leaders were killed, their dreams did not die with them. Overnight, the cause of Irish nationalism became a personal matter of mourning and revenge. It was a moral shock that ended any hope of reform and birthed popular support for complete independence. W.B. Yeats described it perfectly when he said “a terrible beauty” was born that year.

That’s why we remember the Easter Rising. Not because it gained our independence, but because it set Ireland on the path to independence. Once the Rising had happened, there was no stopping Irish separation from Britain. In its place came public enthusiasm, a Republican revolution, and, eventually, independence. When we think about Easter week, we think about how history is shaped by events like these. Sure, they may seem pointless at the time, but they are truly wonderful if they change minds.