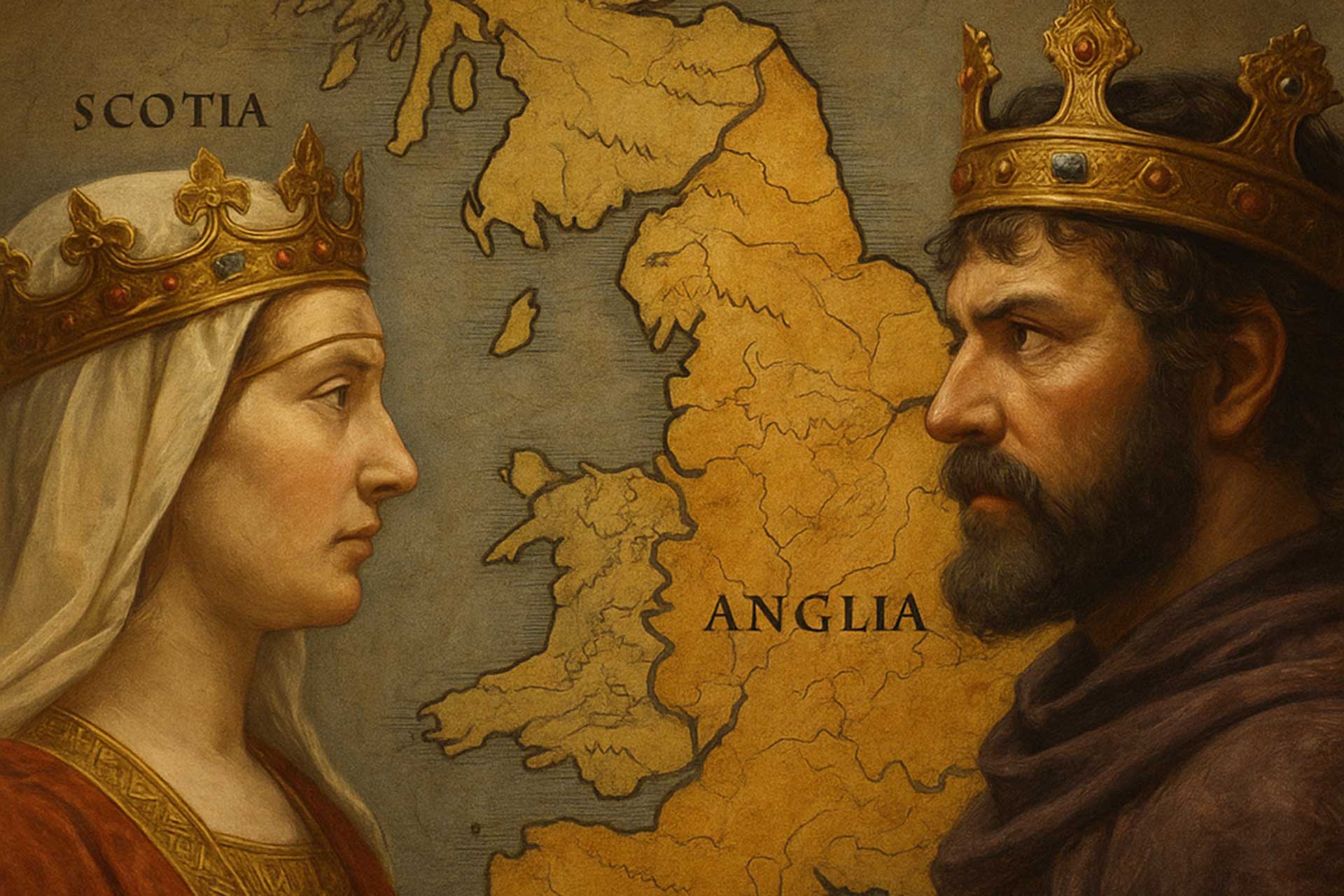

Empress Matilda and The Anarchy: England’s Forgotten Civil War

A Woman Born to Rule, a Country Plunged into Chaos

Empress Matilda was a princess born to be a queen. Instead, she became the victim of betrayal, bloodshed, and a divided kingdom. The only legitimate offspring of King Henry I of England, Matilda had been groomed to rule after the untimely death of her brother William in the notorious White Ship tragedy. Her cousin Stephen of Blois reneged on solemn oaths sworn by the English barons and took the crown after Henry died in 1135, sparking decades of a bloody, tumultuous civil war.

Called The Anarchy, this vicious conflict between supporters of the two claimants to the throne nearly lasted 20 years and destroyed royal power in many parts of England. Towns were pillaged, loyalties tested, and anarchy raged. While it is lesser known than other famous internecine power struggles in English history, it was a critical turning point. At stake in The Anarchy was Empress Matilda’s fight for the crown. This unprecedented and hard-fought campaign would make her England’s first reigning queen and change the course of the monarchy and the future Plantagenet dynasty.

Background: The Line of Succession

Henry I was the youngest son of William the Conqueror and ruled England from 1100 to 1135. He was an efficient administrator who worked hard to centralize royal power. His reign was generally peaceful and prosperous. Henry strengthened royal power throughout England and Normandy. The strong position he was able to attain would be threatened by the loss of his only legitimate son in a shipwreck.

In 1120, Henry’s only legitimate son and heir, William Adelin, along with nearly everyone else in his party, was killed in a shipwreck. The vessel that sank was called the White Ship and went down off the coast of Barfleur. Orderic Vitalis described the reaction to the accident, “The king’s grief was boundless.” The death of his son left the succession in doubt.

Henry married his daughter, Empress Matilda, to Henry V, the Holy Roman Emperor. As Empress, Matilda gained a reputation for being strong and intelligent. After her husband died, she returned to her father’s court. Henry worked to secure his bloodline and arranged for his daughter to succeed him as the first woman ruler of England in her own right.

Henry I secured oaths from his barons to support Empress Matilda as his successor in 1127, 1131, and 1135. It was a controversial move since many people thought England should not have a female ruler. Still, Henry worked to establish a precedent of female rulers in England. Empress Matilda was not a universally popular choice as Henry’s successor, and some of the nobility resented being forced to take oaths to support her.

Henry’s daughter was seen as proud and imperious by some, including her brother, who had been illegitimate. Henry then married Matilda to Geoffrey of Anjou. This move was effective politically but would alienate those suspicious of Geoffrey. The territory Geoffrey ruled was a border region of Normandy. Geoffrey’s relationship with the Norman barons was strained. Empress Matilda’s marriage opened up new dynastic possibilities. However, it would also create issues affecting her ability to rule, as many who should have supported her did not.

The Succession Crisis

On December 1, 1135, Henry I of England, Empress Matilda’s father, died unexpectedly. Henry had reigned for 35 years, and after the debacle of King Stephen’s accession in 1135, he had spent most of his time and energy attempting to ensure that Matilda would succeed him without incident. Nevertheless, his lack of a legitimate male heir and the resistance to the idea of a female monarch had combined to make the succession extremely uncertain. The fact that Henry died in Normandy, far from his English court, and that Matilda did not react immediately created a brief but decisive opportunity for ambitious nobles who sought to seize the throne by force.

Stephen of Blois was a grandson of William the Conqueror and a nephew of Henry I. As one of the most powerful men in the kingdom, he had an obligation and was under oath to support Matilda. However, ignoring his own oath and those of other barons, Stephen quickly crossed the English Channel and galloped to London. There, he gained the support of the remaining political elite by leveraging his influence and popularity as a generous, easygoing individual.

Within a week, Stephen had been crowned at Westminster Abbey. The speed was of the essence. Stephen could give the impression that his accession was legitimate, and he did not want Matilda to gain momentum before it was too late. There was also the question of legality: while Matilda was the appointed successor and Stephen’s claim was weak, the kingdom could not be left without a monarch. “The whole land swore oaths to him,” the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recorded, “and he swore to keep good laws.”

Stephen needed to establish and reinforce his legitimacy in the public’s eyes. In 12th-century England, the Church was a decisive factor in public life, and Stephen had a relative in the right place. Henry of Blois, Stephen’s brother, was the Bishop of Winchester as well as the papal legate. The church’s support made Stephen appear to be acting with God’s approval, an essential step in neutralizing the threat posed by Matilda. The Church’s intervention proved enough to win over the barons who wanted to avoid a civil war.

Naturally, they had their own reasons for doing so, just as the ordinary people did. Geoffrey of Anjou was thought to be pulling the strings through Matilda, and many barons feared his influence. As the Count of Anjou, Geoffrey had his own ambitions in Normandy that threatened English interests. The idea of a woman ruling in her own right was also not particularly popular, despite her imperial rank. Stephen, on the other hand, was an individual who could be easily manipulated. As a king, he could be relied upon to protect the barons’ interests and maintain law and order.

It is safe to say that Stephen was crowned because of a series of favorable events rather than because of a powerful claim. For this reason, the alliances that helped him secure the throne began to dissolve in the months after his coronation. Empress Matilda would not stay quiet forever, and her attempt to take the crown that was rightfully hers gave way to a civil war that would last almost two decades.

The Outbreak of The Anarchy

Empress Matilda, waiting for her moment to strike at her cousin Stephen for the English crown, finally moved into action in 1139. Supported by her half-brother Robert of Gloucester, a respected military leader and magnate, Matilda landed at Arundel and began her advance into the country. Her arrival, though initially hesitant, was the spark that ignited a civil war that would tear the country apart for the next eighteen years. Matilda’s claim to the throne challenged the tenuous political balance Stephen had achieved and would lead to a war fought for personal ambition and principle.

Empress Matilda’s claim was bolstered by disgruntled barons and nobles who had sworn oaths to Matilda’s father, Henry I, and who were unhappy with Stephen’s unpredictable and, some thought, self-interested rule. Matilda was also able to rely on Robert of Gloucester’s influence to gather significant parts of the country to her side. Support bases and communication hubs in the west of the country, notably Bristol, were of particular importance, allowing Matilda and her supporters to maintain a presence and continue their advance across the country.

The war that ensued was both decentralized and vicious. Bouts of fighting, sieges, and skirmishes across the country as the two sides vied for control of territory and advantage. The barons fortified castles, some more loyal to their own ambitions and local influence than to the crown. England was thrown into a period of instability and civil unrest as regional castles and power bases jockeyed for position, frequently changing sides through treason, negotiation, or military force. The impact of the increased violence was felt across the country as no area was left untouched.

A breakdown of order rapidly replaced Royal control of the country, as the leaders were locked in civil war. Chroniclers of the time were deeply despondent at the developments in the country, with the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle lamenting that, “men said openly that Christ and His saints were asleep.”

Travel was made more difficult and dangerous, villages were attacked and looted, and the rule of law was all but non-existent across large parts of the country. The people of England were caught in the grip of a battle for the crown and the greed and viciousness of their local lords.

Conflicts, campaigns, and battles were fought and, in many cases, achieved no lasting result, with neither side able to significantly increase their advantage over the other. Stephen and Empress Matilda both played upon baronial loyalties, the offer of land and titles, and the ties of family to continue the conflict, with little end in sight. England was left to languish in a war that bled both its economy and spirit as towns were besieged and agriculture suffered under the pressures of conscription and destruction.

The period would have a profound and long-lasting effect on the country’s political scene. The Anarchy would severely test the notion of royal succession and demonstrate the weakness of a country divided by dynastic and personal ambitions and greed. The Empress’ campaign was not over, but its initial phase had already begun to change the shape of the English crown.

The High Point: Empress Matilda Nearly Crowned

In the first weeks of 1141, Matilda’s star had never shone so brightly. At the Battle of Lincoln, Robert of Gloucester’s forces overwhelmed the King’s army, leaving the king himself to be captured and imprisoned in Bristol. The tables were finally turned: her enemy was in chains, and with him removed from the scene, Matilda was on the brink of making history as the first ruling queen of England. The chronicler William of Malmesbury noted that Stephen’s capture “greatly encouraged her followers and dismayed her enemies.”

In the spring of 1141, following her resounding military victory, Empress Matilda rode into London. With her rival safely out of the way, Matilda prepared to have herself formally crowned at Westminster Abbey. For a few weeks, it seemed as though the prize of the crown was finally within reach, with the seats of real power hers. Even as she waited for the right moment to ascend the throne, Matilda took to adopting more regal titles, styling herself the “Lady of the English.”

But for all her apparent success and momentum, the situation was soon to unravel. Her continued hold over the throne was always delicate, and despite the propaganda, she had not secured the support she needed to keep it. Even as Matilda set foot in London, she had failed to impress those whose support she needed. Her insistence on raising taxes and her general haughtiness had begun to turn her noble backers against her.

In London, her reputation was not much better. The citizens of London were never enthusiastic about the Empress. The city remained a center of Stephen’s support, and long before her arrival, the common people had been awaiting Stephen’s return to power. As Matilda entered the city in her finery and set up court, their impatience was to become a roar. The people rose in revolt. On the very day of her planned coronation, Matilda was forced to flee the city, taking refuge in Oxford and elsewhere in the west.

She had only briefly held political power, even as she had dominated on the battlefield. The chronicler John of Worcester recorded the incident, writing that “she did not show herself queenly in her dealings,” suggesting that those who had supported her were now more than a little disappointed.

Away from London, Queen Matilda of Boulogne was acting on her husband’s behalf, raising Stephen’s armies and enlisting the support of the Church. The Church had, if only lukewarmly, supported Empress Matilda during her time as regent, but they were not about to stand in the way of Stephen’s return, and were to become a key part of his resurgence. The final straw for Matilda came later in 1141, when Robert of Gloucester was taken prisoner during the rout after the Battle of Winchester. With her chief military strategist in enemy hands, the Empress was desperate to have him back and agreed to the inevitable prisoner swap.

Stephen was released from prison in late 1141 in exchange for Robert of Gloucester, and he was soon back on the throne. The king was by no means back in full strength, but he had held his own and gained enough support to allow him to fight on. With both claimants alive and both unwilling to back down, the Anarchy continued, its end nowhere in sight. Where it had seemed but a few weeks before that the Empress was inevitable, it now seemed that there would be no end to the conflict in the near future.

Legacy and Resolution

Broken by the exhaustion of a long civil war, Empress Matilda began to distance herself from the political situation in England. While her own campaign for the throne had stalled, she increasingly placed her resources and efforts behind her son Henry of Anjou. Matilda continued to offer her advice and political influence in this way, but largely avoided direct involvement in English affairs. She never became queen, but did achieve her dynastic ambition by laying the foundation for her son’s future success.

Stephen almost succeeded in capturing Matilda in 1142, when she was besieged at Oxford. She managed to escape by crossing the frozen Thames from Oxford Castle, but the civil war continued for another eleven years. In 1143, Matilda’s husband, Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou, conquered Normandy in her name, but in England, neither side was able to claim lasting victory. Rebel barons gained greater power in Northern England and East Anglia, while much of the country was left devastated by the regions of major fighting.

In 1148, the Empress returned to Normandy for good, and her eldest son, Henry Fitzempress, took over the campaigning in England. In 1152, Stephen was determined to have his eldest son Eustace IV, Count of Boulogne, recognized by the Catholic Church as the next king of England, but the Church refused to do so. By the early 1150s, most barons and the Church were tired of the conflict and were instead pushing for a long-term negotiated peace.

Matilda’s son had also emerged as a more charismatic and competent leader than his rivals, commanding the support of friends and former enemies. In 1153, Henry began a new military campaign in England and was successful in both military and diplomatic manoeuvres. Henry’s rising power led to negotiations between his supporters and King Stephen’s enfeebled administration.

The formal end of the civil war came with the Treaty of Wallingford in 1153. Stephen would remain king for the rest of his life, but agreed to recognize Henry as his heir apparent. Though not the result Empress Matilda had initially fought for, this was still a considerable political victory for her family. As King Stephen’s health failed, this agreement avoided an uncertain succession and further bloodshed in England.

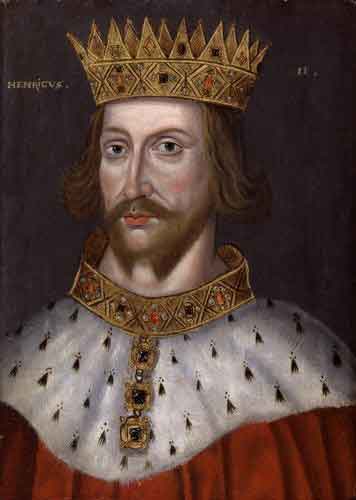

Stephen died in 1154, and Henry was crowned as King Henry II. He began the Plantagenet dynasty, one of the most successful royal families in English history. Empress Matilda was now the mother of an English king and the grandmother of an heir. While she had never been queen in her own right, she was still victorious in a dynastic sense, as her political strength and will had secured the throne for her family.

Empress Matilda spent her final years in Normandy, continuing to offer her counsel and support to her son as an advisor. She died in 1167, having outlived her enemies and seen the fruits of her labour settle the English crown. Her tomb in Rouen is inscribed with the words: “Great by birth, greater by marriage, greatest in her offspring.” This fitting epitaph reflects her life – one of dynastic ambition, personal survival, and long-lasting influence over the English monarchy.

The Anarchy remains a sometimes forgotten part of English history. It was a turbulent period, which transformed the monarchy and tested the very idea of royal succession. Empress Matilda’s life, and her path to influence in England through her son Henry II, is a dramatic example of ambition, resistance, and dynastic power that continues to be felt in British history today.

Why The Anarchy Matters

The Anarchy holds a crucial place in English history, providing several key lessons and insights. While at its heart it was a dynastic conflict over the succession to the throne, its broader impact on the monarchy and the law was far-reaching. The civil war exposed critical weaknesses in the systems governing royal succession. Without established legal mechanisms to ensure King Henry I’s will was followed, Stephen’s usurpation demonstrated the vulnerability of power to individuals who were willing to defy oaths and overrule named heirs. This period highlighted the need for a more definitive and enforceable line of succession, a lesson that would resonate with future English monarchs.

The civil war also led to a fracturing of centralized royal power. Nobles used the period of conflict to increase their own power, building castles without royal sanction and acting with greater autonomy. Chronicler William of Malmesbury famously stated that “Christ and His saints slept” during this time, alluding to the lawlessness and despair that characterized much of the kingdom. This weakening of royal authority during The Anarchy would necessitate later efforts at consolidation and restoration, affecting reforms by Henry II and his successors.

The role of Empress Matilda in the conflict and its aftermath should not be underestimated. She set a precedent by establishing that a woman could claim the English throne and mount a credible, sustained challenge to it. Denied a coronation, she would still lay the groundwork for her son, Henry II, to inherit and solidify their royal claim. Matilda’s impact on the perception of female rulers would echo through the centuries, influencing figures such as Elizabeth I and Victoria.

Matilda’s struggle can be seen as the beginning of a slow but significant shift in attitudes toward women in power. Her intelligence, political savvy, and resilience carved out a place for female leadership in a time when it was not the norm. Though her contemporaries were mixed in their support for her claim, history has been kinder in remembering her. She is a figure of ambition and endurance, unwilling to be constrained by the limitations of her time.

The broader social and economic impact of The Anarchy was devastating, with lessons about the human cost of disputed succession and civil war. The famine, looting, and general lawlessness that afflicted the population during these years left a lasting mark on English society. These events highlighted the importance of a strong, undisputed monarchy in maintaining social order and preventing such widespread suffering, influencing the governance of medieval and early modern England.

In conclusion, the Anarchy matters because it was a formative event that reshaped the monarchy, tested the limits of political order, and introduced a woman who would change perceptions of female leadership. The lessons of The Anarchy are embedded in the very fabric of English history and continue to inform our understanding of royal power and succession. Empress Matilda’s legacy endures not just as a tale of personal ambition thwarted, but as a catalyst for change in a kingdom and in the royal tradition itself.

Conclusion

Despite losing the ultimate battle for the throne, Empress Matilda’s life was a pivotal chapter in medieval succession and governance. Her relentless pursuit and temporary victories established strong legal and political precedents, particularly regarding the crown’s inheritability and contestability. Her audacious challenge to the era’s gender norms laid the groundwork for future female monarchs such as Elizabeth I and Victoria, reshaping perceptions of women in leadership roles.

The period of Anarchy is sometimes overshadowed in the broader tapestry of English history. However, its ripples profoundly affected the monarchy and legal framework. It highlighted the perils of ambiguous succession and the fragility of centralized power. It was more than just a historical footnote; it was a defining era, marked by conflict, resilience, and the indelible legacy of a woman whose influence endures through the Plantagenet dynasty she helped found.