Garibaldi and the Popular Unification of Italy

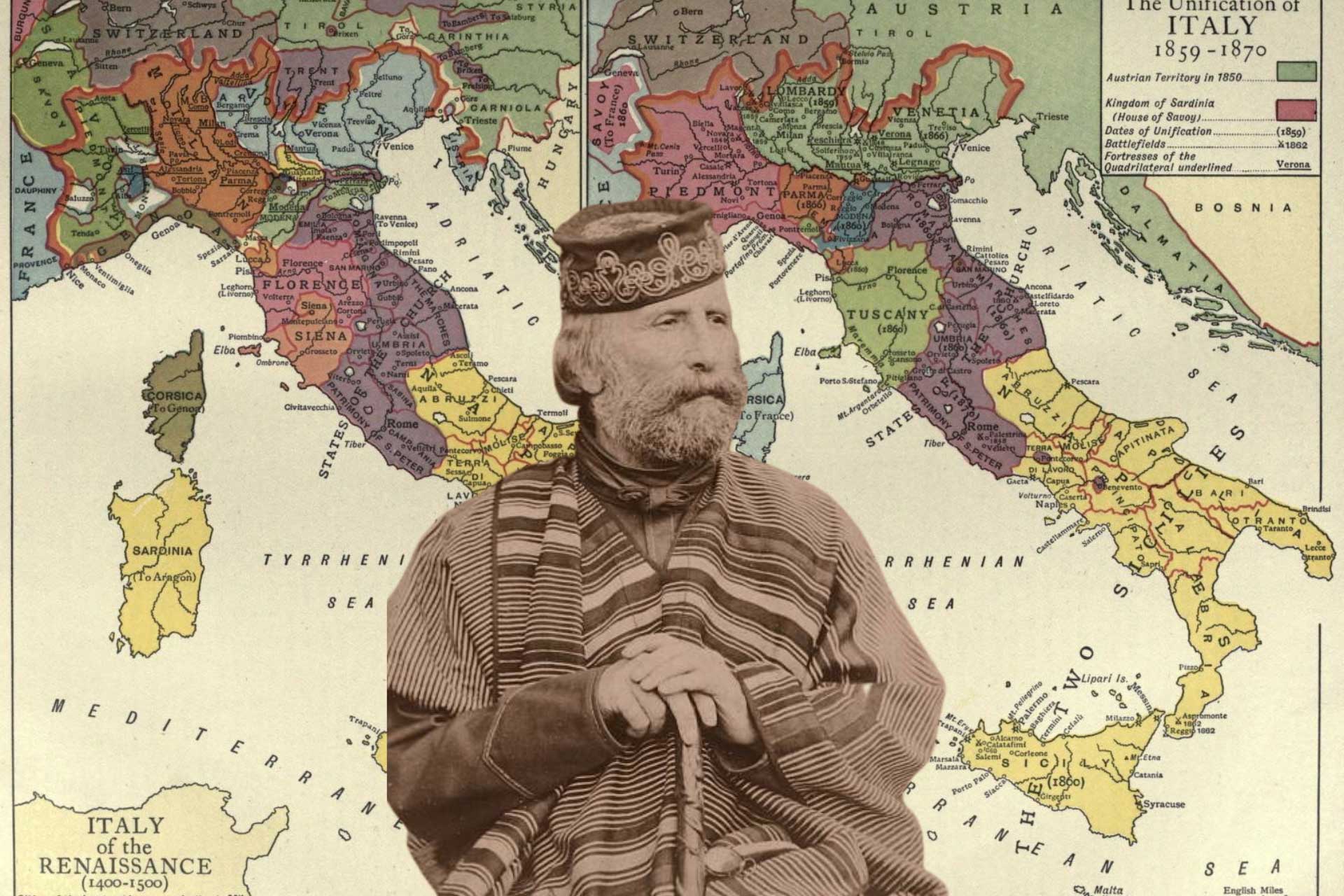

In the early 1800s, Italy was not a country, but a collection of kingdoms, duchies, and provinces ruled by foreign powers. Northern Italy was dominated by Austria, central Italy by the Papal States, and the south by the Bourbon monarchy. This division of Italy created barriers to trade, political reform, and national feeling. As revolutions swept across Europe, Italians increasingly demanded to know why their language, culture, and history had been divided by borders created by outside powers. The idea of a united Italy shifted from the pages of intellectuals’ books to the streets of Italian cities, as ordinary Italians began to imagine a country of their own.

The living embodiment of this popular nationalism was Giuseppe Garibaldi. A soldier forged in exile and revolution, Garibaldi relied not on royal armies but on volunteers, peasants, and workers. “Here we make Italy or die,” he was said to have declared. Garibaldi would unify Italy not through negotiations, but by bringing provinces to independence through mass support, volunteer armies, and fast-moving revolutionary warfare that transformed local insurrections into national upheaval.

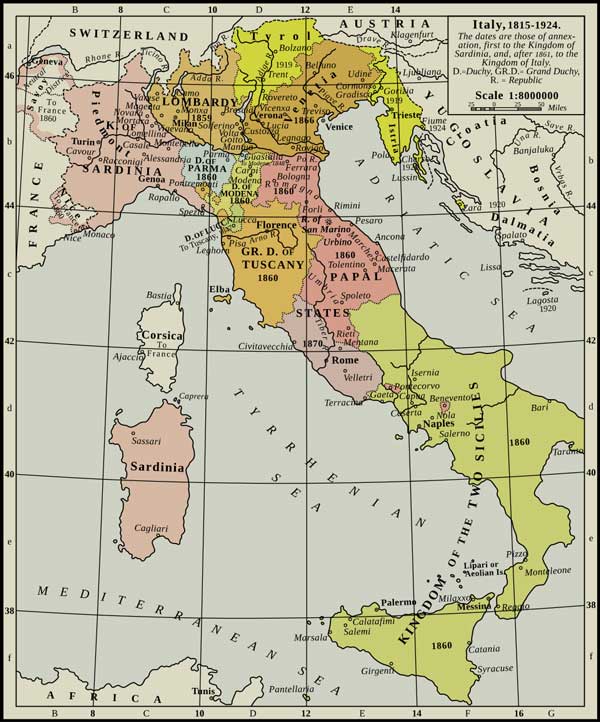

Italy Before Unification

Italy, before unification, was divided into several states, each with its own government, laws, and customs. Political unification was limited, and the Italian Peninsula comprised various kingdoms, duchies, city-states, and the Papal States. The lack of central authority made travel and trade slow and expensive, and political censorship and repression were common. The idea of an Italian nation-state did not yet exist; instead, there were local and regional identities, as Italians were divided by centuries of separate development.

Italy had also long been a battleground for foreign powers, further deepening its fragmentation. The northern regions, in particular, had been under the influence of the Habsburgs of Austria, who directly controlled Lombardy-Venetia and exerted significant sway over other Italian states. Austrian authorities and their troops were often the local enforcers of order, censorship, and suppression of dissent. This could be swift and brutal, as seen in their response to uprisings and revolutions. Prince Metternich of Austria reportedly said, “Italy is nothing but a geographical expression.” This quote epitomizes the lack of legitimacy that foreign rulers gave to the Italian people and their aspirations for self-rule and independence.

In many places, Italians were ruled by local princes or dynasties who were often as unpopular as foreign rulers. Many of these rulers were absolute monarchs who resisted reform and were unresponsive to popular demands for greater rights and representation.

This led to widespread resentment among peasants, workers, and the emerging middle class who were burdened by taxes, conscription, and a lack of political voice. This was a period when new liberal and nationalist ideas were spreading from France and other places, but they often met with rigid political structures in Italy.

Growing Nationalism and Liberalism. Nationalist feelings in Italy were increasing during this period. Secret societies, such as the Carbonari, spread nationalist and revolutionary ideas. There were several failed uprisings, which created martyrs and myths that further fueled the desire for unification and independence. As time went on, many Italians were frustrated with foreign domination and local despots. They were ready to follow leaders who could promise them a sense of liberation, unity, and a shared Italian identity.

Garibaldi’s Revolutionary Formation

Giuseppe Garibaldi’s political life began early, in the republican and anti-foreign ferment. A young sailor from Nice, he was caught up in the national struggle led by Giuseppe Mazzini and in the ranks of Young Italy. In 1834, he took part in a failed rising against the Kingdom of Sardinia. The insurrection was quickly put down. Garibaldi was condemned to death in absentia, and he went into exile, beginning his life as a fugitive revolutionary.

Exile took Garibaldi far from Italy, but it was a continuing revolutionary education. In South America, he fought in the Ragamuffin War in Brazil and later in Uruguay’s civil wars. There, he fought to defend Montevideo, leading volunteer forces in campaigns that combined nationalism and mass support. The conflicts were fluid, unlike earlier European wars of manoeuvre; fighting involved civilians as well as regular armies and irregulars, in terrain as varied as grasslands and mountain forests.

Portrait de Giuseppe Garibaldi circa 1866 or 1867

South America was Garibaldi’s military laboratory. He learned that small, committed forces could defeat larger armies by speed, surprise, and local alliances. He perfected the mobile column, the sudden landing, the rapid retreat; avoiding decisive battles but bleeding the enemy.

Garibaldi’s South American volunteers were known for wearing red shirts. He had obtained the original shirts from slaughterhouse workers in Uruguay and Brazil during the 1840s; a practical item of clothing that would become a potent and inspirational symbol and a forerunner of the uniform he would later adopt for the campaigns for Italian unification. His red-shirted volunteers were both fighters and symbols, soldiers and people.

Garibaldi was forged as a leader who believed that liberation had to be a mass affair. He was no general barking orders from the rear. He was a leader who came from the people. By the time he returned to Europe, Garibaldi was no longer just an Italian patriot. He was a veteran revolutionary, ready to apply the lessons of people’s war to the struggle for Italian unification.

Return to Northern Italy and Early Campaigns

Garibaldi had returned from South America not because he longed for his homeland, but because the time was right for a political breakthrough. The Brazilian and Uruguayan exile had given him experience as a military commander, but he never forgot his original mission of Italian liberation. In 1848, when revolutions were erupting across Europe, Garibaldi felt that to hesitate was to lose. “Italy has need of all her sons,” he wrote, justifying his return from exile to a potentially treacherous homeland still under foreign control.

At the heart of the conflict was northern Italy, where the Austrian Empire had imposed its authority over the regions of Lombardy and Venetia. Austrian garrisons and armies maintained order by taxation, censorship, and repression. The Habsburg administration was efficient and modernizing, but highly unpopular. Economic and political tensions were reaching a breaking point, making the area ripe for revolt. Garibaldi entered Lombardy-Venetia with the clear understanding that any success would be a direct blow to Austria’s power on the peninsula.

His first campaigns of 1848–49 were headlong and sometimes haphazard. He took part in the fighting in Lombardy and then joined the defenders of the short-lived Roman Republic. He was soon driven out by the combined might of the Austrian and French armies, which returned him to South America. But these setbacks were not in vain. Garibaldi learned from them that Austrian power, while strong, was not invincible.

In 1859, when he returned to the north for the Second Italian War of Independence, he had a clearer sense of strategy. Allied with the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia, he commanded the irregulars on the Alpine frontier known as the Hunters of the Alps. His bands and militias tied down Austrian forces and disrupted their logistical arrangements. They also confused and delayed the Austrian command and control, especially during the initial phase of the war, in which Sardinian forces were making rapid gains. Austrian commanders were forced to divert their troops, weakening their strength in other sectors.

In the end, Austrian power in northern Italy was clearly sapped. The battlefield losses inflicted by the Franco-Piedmontese combined armies and Garibaldi on the flanks forced Austria to give up Lombardy. Austria held on to Venetia until 1866. As one Austrian officer later wrote, there was “a population no longer obedient.”

The Redshirts and Grassroots Warfare

Giuseppe Garibaldi was Italy’s most famous revolutionary by the late 1850s. He had won fame not as a king or as the commander of a state army but through audacious campaigns in which he fought side by side with ordinary people. Newspapers across Europe portrayed him as a romantic man of the people. A supporter once wrote that Garibaldi “carried a nation on his shoulders,” and there was some truth in the hyperbole.

The Redshirts were volunteers rather than professionals. Garibaldi eschewed bureaucracy and formal hierarchies. He instead commanded fluid forces of motivated fighters with a good deal of experience but little training. The Italian masses may not have been professional soldiers, but a fierce belief united them in the ideals of liberation. The uniforms were also distinctive. Garibaldi first wore a red shirt in South America, and his volunteers soon followed suit. The color identified them, but did not mark rank or privilege.

The volunteers were drawn from peasants, workers, artisans, and students. In the countryside, men took up rifles and farm implements to fight for freedom. In the cities, artisans and dockworkers formed militia companies. Garibaldi was adept at understanding their frustrations with taxes, foreign rule, and local oppressors, and he spoke directly to these sentiments. His calls to arms were neither ideological nor subtle but instead stark and urgent.

Popular support often decided battles. As Garibaldi and his Redshirts entered towns, resistance often crumbled. Municipal leaders offered their support. Churches rang their bells. Farmers offered food and fodder. Garibaldi did not need to occupy territory where the locals were hostile to his cause. Instead, they joined his forces, which expanded after every battle as they were seen as liberators rather than occupiers. Each victory became easier than the last.

Locals also aided the Redshirts in intelligence and logistics. Villagers knew the local terrain, guided his men through the mountain passes, warned of enemy troop movements, and hid his men in their homes when they were on the run. As Garibaldi would later write, “the people were our fortresses.” Garibaldi did not need walls, towers, or garrisons when the locals were on his side.

The Redshirts made warfare a popular, national struggle. Garibaldi’s campaigns were a weapon that defeated not only armies but also turned an entire society toward unification. The Italian masses did not simply watch as the country was unified; they made it happen. By taking the act of liberation into their own hands, the Redshirts made unification an earned rather than a granted outcome.

Grassroots warfare also had political consequences in Italy. It showed that the nation could be unified from below rather than simply through diplomacy or dynastic leadership. Garibaldi and his Redshirts proved that popular will, when organized and mobilized, could redraw the map of Europe.

The Expedition of the Thousand (1860)

In May 1860, Giuseppe Garibaldi led one of the boldest military adventures in modern times. The Expedition of the Thousand would take approximately 1,000 volunteers from northern Italy and across the Strait of Messina to the western coast of Sicily, where they landed at Marsala. The troops were lightly armed and hopelessly outnumbered. They had speed, surprise, and popular sympathy on their side, but little else in the way of military strength. Observers expected a short campaign, a humiliating repulse for Giuseppe Garibaldi and his Thousand. But he was gambling that momentum would be more critical than forces, and his luck was good.

The first test of wills was at Calatafimi. The revolutionary volunteers faced well-armed Bourbon soldiers. Giuseppe Garibaldi’s men were heavily outnumbered and could have easily turned back. As they hesitated, legend has it that Garibaldi raised his voice and shouted: “Here we make Italy, or we die.” It was a small victory, a relatively easy skirmish with no earth-shattering consequences for the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. But its symbolic value was immense: it had shown that the Bourbon army was not invincible, that revolution could be made.

The campaign quickly gathered steam. As Giuseppe Garibaldi marched from Calatafimi to Palermo, he was joined by more and more supporters: farmers, laborers, and small-town dwellers who provided the necessary food, guides, and intelligence for the journey. The Thousand were no longer a conquering army, but a moving revolutionary column, riding a wave of widespread resentment against Bourbon officials and local tyranny.

The siege of Palermo was a watershed. As Giuseppe Garibaldi’s volunteers fought the Bourbon troops outside the city, the insurrection spilled over inside its walls. Barricades sprang up in the streets as mass resistance challenged Bourbon rule, rapidly overwhelming royal authority. After a few days of street-fighting, the Bourbon garrison fled, and Garibaldi’s campaign had the capital of Sicily firmly in hand. Palermo was not won by the Thousand alone but by an alliance of fighters and citizens.

From Palermo, other towns and cities of Sicily fell one after the other into Garibaldi’s hands, often without firing a shot. Local officials hurriedly resigned, local militias and other law enforcement agencies changed sides, and provisional governments quickly sprang up, all declaring their support for the unification cause. Success bred success. Giuseppe Garibaldi made sure he was not in any one place for long, leaving in his wake the dissolution of Bourbon power, province by province.

By the summer of 1860, Bourbon power in Sicily had effectively come to an end. The Expedition of the Thousand had been a remarkable military adventure. A volunteer force of a few thousand successfully challenged the power of an established regime and won. The Expedition transformed Giuseppe Garibaldi from a romantic revolutionary into the key player in the unification of Italy.

Liberation of Southern Italy

Secure in Sicily, Giuseppe Garibaldi decided to take the fight to the Italian mainland. In August 1860, his Redshirt army crossed the Strait of Messina and landed in Calabria. The move was risky, but Bourbon forces on the mainland were disorganized and disheartened. Garibaldi moved quickly, believing that rapid action could break resistance before it could coalesce.

As the Redshirts marched north through Calabria, they faced minimal resistance. Royal troops frequently deserted or melted away when confronted by volunteers, unwilling to fight for a doomed regime. Local populations often welcomed Garibaldi’s forces, providing sustenance, shelter, and intelligence. Each town that capitulated without a fight only furthered the sense that Bourbon authority was already a hollow shell.

The psychological disintegration of the Bourbon state proved as important as military factors. Garibaldi’s fame preceded him, spreading terror among officials and hope among the general population. Provincial administrators abandoned their posts, the courts of law ground to a halt, and royal orders were ignored. One contemporary observer wrote that “the government vanished before a shot was fired.”

The capital of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, Naples itself fell with no major engagement. King Francis II of the Two Sicilies abandoned the city, fleeing north with the remnants of his loyal army. On September 7, 1860, Garibaldi entered Naples by train and was greeted by cheering crowds rather than organized resistance. It was one of the most dramatic occupations of a European city in history.

With Naples in their hands, the remaining bastions of Bourbon power in southern Italy began to collapse. Provinces proclaimed their loyalty to Garibaldi’s provisional government, and local militias were mobilized to replace royal troops. The speed and thoroughness of the collapse took European observers by surprise, who had assumed the Bourbon monarchy was both stable and well defended.

Garibaldi’s government was a brief interlude, and he showed little interest in seizing power for himself. He tended to present southern Italy as liberated rather than conquered. The liberation of the south indicated that unification was not simply the work of armies marching across the peninsula, but was driven by popular revulsion against an exhausted and corrupt regime.

By the autumn of 1860, the Bourbon state had effectively ceased to function. Southern Italy had been liberated, completing the most dramatic phase of Italian unification. The result proved that mass support, momentum, and a sense of legitimacy could defeat even long-established monarchies.

Central Italy and Pressure on the Papal States

Garibaldi’s triumphs in the south of Italy had a profound impact on the political climate in the north, particularly in central Italy. The successes of the Expedition of the Thousand demonstrated the vulnerability of the Papal States, which still held significant territories in central Italy under the pope’s temporal authority. Italian nationalists viewed these regions as the remaining territories to be unified with the north, while the Church saw Garibaldi as a direct threat to its temporal and spiritual power.

Garibaldi had long expressed animosity toward clerical power, particularly the influence of the Jesuits. He saw them as collaborators with foreign rulers and impediments to national unity. In a letter, he stated, “The Jesuits are the most dangerous enemies of Italy.” Jesuit colleges in the territories liberated by Garibaldi’s followers were closed, and the order was expelled from those regions. This was part of Garibaldi’s broader stance that the Church’s political power in Italy must be curtailed.

The hostility between Garibaldi and the Jesuits was deeply unsettling to Catholic authorities of the time. The Jesuit order, for its part, perceived Garibaldi as a revolutionary threat to the religious and social order. As political and social unrest spread, some members of the Jesuit order sought refuge in other countries, including the United States.

In central Italy, Garibaldi’s actions inspired a series of uprisings and revolts, particularly in the regions of Umbria and the Marche. There were local insurrections against papal rule, some of which were explicitly in support of joining the Kingdom of Sardinia. Volunteers, inspired by Garibaldi’s call to action, traveled to these regions to support the revolts. These uprisings were often spontaneous and locally organized rather than directly orchestrated by Garibaldi.

The revolts in central Italy put the Papal States on the defensive. Papal forces were unable to quell the uprisings effectively, and the Austrian protection that had previously deterred rebellion could no longer be guaranteed. The political situation in central Italy became increasingly fluid and contested.

Garibaldi’s immense popularity and his association with the cause of unification also posed a dilemma for the more moderate Italian leaders, such as Count Camillo di Cavour. While they too desired unification, they were concerned that Garibaldi’s radicalism and willingness to defy international norms might provoke foreign intervention. His rhetoric of marching on Rome alarmed both the Vatican and foreign powers.

The threat to Rome became the subject of urgent diplomatic efforts. The French government, which had a treaty obligation to protect the papacy, explicitly warned that an attack on Rome would lead to war with France. Pressured by these diplomatic threats, Garibaldi was effectively contained, but his actions had already irreversibly altered the political dynamics in central Italy.

By late 1860, the momentum for unification was clearly in favor of the Italian nationalists. The Papal States were politically isolated, popular revolts had further weakened clerical power, and the territories of central Italy were on a path to incorporation into the unified Kingdom of Italy. Even without the capture of Rome, Garibaldi had succeeded in making the temporal power of the papacy untenable.

Garibaldi and Veneto, Trentino, and the North

Garibaldi was not through with Italy’s north. The big prize, the large Italian-speaking provinces of Veneto and Trentino, remained in Austrian hands. Unification without them was not complete unification for Garibaldi. To him, unification was a popular war that had to be completed.

Garibaldi once again led volunteers in campaigns in Lombardy and into Trentino during the Third Italian War of Independence in 1866. He commanded the Corpo Volontari Italiani and once more employed the lightning-raid tactics he had first developed in campaigns 30 years earlier. The purpose was to stir up revolt among the local population and to tie down Austrian forces in the mountains.

The result at Bezzecca was a significant military victory for the volunteer forces over an imperial army. Garibaldi’s actions during the 1866 war strained Austria-Hungary’s resources, even as the Italian regular army was being defeated in the main areas of conflict. Prussia’s defeat of Austria ultimately decided the Italian victory, but Garibaldi’s efforts tied down enemy troops and raised Italian morale. His famous reply, “Obbedisco” (“I obey”) when told to stop advancing, would serve as a cultural meme for generations as the portrait of a reluctant patriot.

The Austrian cession of Veneto to Italy in the 1866 peace was a significant step in unification. While diplomats would finalize the transfer, Austrian rule there had become untenable due to popular agitation and military pressure. Trentino, however, remained outside of Italy. Garibaldi did not accept this, and his life to the end would be dedicated to supporting nationalist agitation there and speaking out against the continued existence of Austrian rule over Italian-speaking people. For Garibaldi, unification was a crusade and not a treaty.

After the proclamation of Italian unity, Garibaldi’s life would be spent as a symbol of Italian resistance to Austrian rule in the north. His very presence there was a reminder that Italy had been forged not just by diplomacy but also by popular warfare. Austrian authority in the lands they retained in the north would linger, but only by the constant application of force, and only under constant pressure from the ideas and ideals that Garibaldi had done so much to spread.

The Handovers to the Italian Kingdom

As Garibaldi’s campaigns liberated much of Italy, an important question arose with each victory: who would be in charge of these newly freed lands? Garibaldi was a lifelong republican, but he was also a realist, and recognized that unification had to mean political unification, rather than multiple governments based on the same ideals but operating independently. To achieve this, he opted to cede control of the territories he conquered to Victor Emmanuel II of Piedmont-Sardinia, the king whose lands and family were best placed to unify Italy.

The most famous of these events was in October 1860, when Garibaldi met Victor Emmanuel outside the town of Teano. Garibaldi formally handed over his command of southern Italy and greeted the king with the title of “King of Italy. It was a symbolic act that closed a significant chapter in the revolutionary movement in Italy. From then on, Italy would be united under a constitutional monarchy.

This decision of Garibaldi’s came as something of a shock to those of his followers who favored establishing a republic in Italy. He famously said that, if left to his own devices, he would have made Italy a republic overnight. However, he also recognized that, while Italy was still divided, disputes over the form that any new government should take would only hinder unification, and potentially open the way for foreign intervention or civil war. “We have not yet one government,” Garibaldi once wrote; “when we have that, we will think of the form that it should take.”

Accepting this reality required a great deal of personal sacrifice. Garibaldi was at the peak of his power and popularity when he ceded control to Victor Emmanuel, and he could have easily leveraged this support to seize power for himself. Instead, he returned to a private life, and while he was invited to take a position in the new government, Garibaldi turned it down. This was one of the great paradoxes of Garibaldi’s legacy. Although he was Italy’s most famous revolutionary, he never sought to become its ruler and was content to step away from power.

The relationship between Garibaldi and the Italian state would again come under strain in 1866, when the Italian government ordered Him to halt his invasion of Austrian-controlled territory. Garibaldi’s reply was the single word “Obbedisco,” or “I obey.” It is one of the most famous quotations in Italian history, and it exemplifies the relationship between Garibaldi and the Italian state. By saying nothing more, Garibaldi expressed not only his frustration but also his discipline and acceptance of national command.

In many ways, Garibaldi’s handovers of control of his conquests to Victor Emmanuel defined the Italian state that would come after the Risorgimento. They established the precedent that unification would happen through popular revolution combined with monarchical rule. Garibaldi’s decisions, however reluctant, were as important in preventing further civil war and ensuring international recognition as his military victories were. By setting aside his desire for power and autonomy, Garibaldi helped make revolution into nationhood.

Popular Unification Versus Elite Control

Garibaldi had enacted one strategy for unification, and those in the seats of power in Italy another. The Sicilian champion had liberated provinces through volunteer armies, patriotic songs, and solidarity. Diplomat Camillo di Cavour grew the Italian state through treaties, plebiscites, and agreements. In 1861, these roads intersected. Garibaldi championed the idea that national unification must be by the will of the people; the Italian elite preferred a managed process with less uncertainty, which would lead to international acceptance.

The differences in methods and speed were telling. Garibaldi’s advance was rapid; he took territory before Austria or the other great powers had time to react. Cavour was more careful, maintaining a complex balance between France, Austria, and Britain. A contemporary observer remarked that Italy was being made “by sword and pen at the same time,” a dual process that generated both friction and achievement.

Garibaldi’s conquests, meanwhile, produced political facts that elite planners had not yet anticipated. It was one thing to free a town or province; quite another to turn it back to the King of the Two Sicilies or to the Pope. Once Garibaldi had taken control, public enthusiasm made such a reversal impossible. Even conservative leaders grasped that refusing unification risked social disorder. In this way, Garibaldi’s victories accelerated the unification process by creating a new reality that diplomacy could not deny.

However, annexation also brought unification in the south and center of the Italian peninsula; the popular demands of the people faded from view. Peasants who had supported the Redshirts expected land reform, greater local autonomy, or at least tax relief. What they often found instead were new administrative structures that preserved existing social hierarchies. Unification came, but social change did not.

This created disillusionment, and in the South, that disillusionment at times turned to resistance. Former supporters resented a distant, centralized state that appeared to have handed the peninsula over to the elites. The dream of liberation collided with the realities of a centralized state. As one polemicist wrote, “Italy is made; but the people were not consulted after the battle.”

The Italian monarchy and Cavour had prioritized order. They worried that popular mobilization would continue, and eventually lead to social revolution. Stability, they argued, was the necessary cost of independence and survival in a hostile Europe. Garibaldi grudgingly acquiesced to this logic, but the price was real.

The outcome was a unified country shaped more by elite power than by popular sovereignty. Garibaldi’s campaign had shown that a nation could be built by popular action, but also how easily that power could be corralled, once victory had been won.

Italy was whole, but divided between the ideal of popular unification and the reality of centralized power.

The Unfinished Liberation

Italian unification would be delayed by another ten years after Garibaldi’s greatest triumphs. Rome remained outside the Italian state, defended by French forces and by the Pope’s temporal power. Italy had been made in most of its continental territory by 1861, but without its historic capital. The contrast was unacceptable to Garibaldi and his supporters. For them, the nation could not be complete while the Eternal City was separated from it.

Garibaldi had never countenanced the exclusion of Rome. He viewed it as both a political and a symbolic objective, and as the final vindication that unification was the people’s creation. “Rome or death,” he now insisted, with the same exhortatory cadences he had employed on campaign ten years before. This time, though, Rome was different. A direct attack on the city would be an act of war against France and leave the young Italian state diplomatically isolated.

In 1862, Garibaldi tried to march on Rome without official sanction. At Aspromonte, his volunteers were intercepted by Italian troops, their old enemy and erstwhile ally. Garibaldi himself was wounded and arrested. He became, in effect, a prisoner of the state that had come into being in large part through his own efforts. The moment was illustrative of the limitations of mass revolution in a country ruled by a monarchical government.

The same fate would befall him years later. In 1867, Garibaldi again advanced on Rome, once more at his own risk and without government authorization. The attempt was frustrated by French intervention at Mentana, where breech-loading rifles cut bloody swaths through Garibaldi’s volunteers. The result was conclusive. Popular enthusiasm was no longer sufficient to break the grip of international power politics and state authority.

The episodes at Aspromonte and Mentana pointed to an inconvenient truth. The Italian kingdom could not complete unification through popular revolt but only through the diplomacy of its own government. Garibaldi’s approach had been practical against local despots and an overstretched empire, but it was no longer effective in the face of great-power alliances.

Rome was annexed in 1870, but by forces of circumstance, not by mass volunteerism. France was defeated by Prussia in the Franco-Prussian War and forced to withdraw its troops from Rome. The Papal States were left defenseless, and the Italian army moved on Rome. Italian soldiers entered the city to take control with only token resistance from the Papal militia. Unification was complete, and Garibaldi was a side-show.

The delay in unification had revealed the limits of popular revolution against foreign and monarchical forces once a state had come into being. Garibaldi could make Italy, but he could not mold it entirely to his own revolutionary precepts. The nation was now unified, but its birth had unleashed forces that it could not always control.

Legacy of a Continental Liberator

Giuseppe Garibaldi retired from public life in old age, though never from public view. He lived for years on Caprera, an island off the coast of Italy. He wrote memoirs and received visitors, but mostly he simply lived. He lived as he had always done, modestly, without ceremony or much adornment. It was an existence tempered by a mix of pride and disappointment. He died in 1882, prompting public mourning across Italy and beyond. Newspapers referred to him as “the soldier of liberty” but it was a title he had earned from nearly half a century of sacrifice and action, rather than official rank.

Garibaldi’s significance is found more in liberation than in government. Garibaldi did not unite Italy on paper only; he also did so by liberating it, region by region. In Sicily, in Naples, in many other towns and areas, the cause of national unity was popular because Garibaldi liberated the people. He became famous because people heard about him, saw him arrive with a few volunteers, and then saw him depart, leaving a new political reality in his wake.

For this reason, Garibaldi’s fame traveled beyond Italy. He had already gained experience as a fighter in South America, and later his fame inspired would-be revolutionaries throughout Europe and the Americas. There were admirers of Garibaldi in France, Greece, Mexico, and even the United States. Abraham Lincoln allegedly offered to give Garibaldi command of an army to fight in the American Civil War.

Garibaldi set an example for later popular revolutions. His use of volunteers, speed, moral and popular motivation, and more, was all adapted by later nationalist, anti-colonial, and anti-imperial fighters. Garibaldi demonstrated that even the old empires and regimes could be successfully challenged without requiring an army the size of a state. One observer later wrote that Garibaldi showed that “the people themselves could become history’s decisive force.”

But the myth of Garibaldi is in danger of obscuring the reality. The new Italy that Garibaldi helped liberate was still a land of distinct and separate regions, primarily the north and the south. The Italy that Garibaldi fought for did not become uniformly prosperous or equal. Many who had followed Garibaldi expected land reform, inclusion, and more that would not materialize. The Italy that Garibaldi liberated was also often one that did not live up to the Risorgimento ideal.

Garibaldi recognized the problem. He supported workers’ causes and often criticized the very monarchy that he had helped to empower. “I have made Italy,” Garibaldi reportedly said in old age, “but I cannot make Italians equal.” He had done much, but had been unable to control or even influence all of the forces that his actions had set in motion.

In this way, Garibaldi is both a hero and a warning. He liberated vast territory and changed the map of Europe, but he could not control what came after his revolution. His life is a lesson that revolution can unify a country and inspire a people, but that it cannot of itself deliver on the promises that give revolution its power.

Remembering Garibaldi

Garibaldi liberated much of Italy not by fiat, but by revolt. From Sicily to Naples, his armies of volunteers overturned the ancient régime and allowed local insurrections to determine their own fate. These victories were won by rapidity, improvisation, and numbers rather than the weight of statecraft. Garibaldi’s expedition demonstrated that Italian unification could be a revolution from below, as towns and provinces throughout the peninsula linked up to the national movement because they had fought for it themselves. In the words of one contemporary, his power was that “the people followed him before governments did.”

Italian unification cannot be understood without Garibaldi, because it was Garibaldi who gave the nation revolutionary content. The warfare from below made the ideals of nationalism concrete, fusing regions in the crucible of a shared struggle. Diplomacy and the monarchy finalized the state, but Garibaldi made unity imaginable and real. His legacy lives on as a reminder that Italy was not only negotiated into existence, but was also carried on the shoulders of volunteers, rebels, and ordinary people who believed that their own hands could make a nation.