Joaquin Murrieta: The Mexican Robin Hood of the Gold Rush

Joaquin Murrieta was one of California’s most notorious and controversial Gold Rush-era figures. He was reputedly either a cruel robber who murdered mining families or an avenger of injustice. Newspaper articles, court testimonies, and dime novels circulated wild tales of Murrieta’s deeds, often without distinction between truth and fiction. Murrieta became infamous during the lawless 1850s, when vigilantism, racism, and mining violence were facts of life in the goldfields.

Murrieta gained the nickname “Mexican Robin Hood” after stories claimed he robbed Anglo prospectors and authorities, and fought back against Mexican civilians being victimized. Whether true or not, Murrieta’s legend cannot be extricated from California’s longer history of dispossession and racial violence. Born into a world shaped by colonialism, conquest, and anti-Mexican sentiment, Joaquin Murrieta was less exceptional than you might think.

California Before the Gold Rush

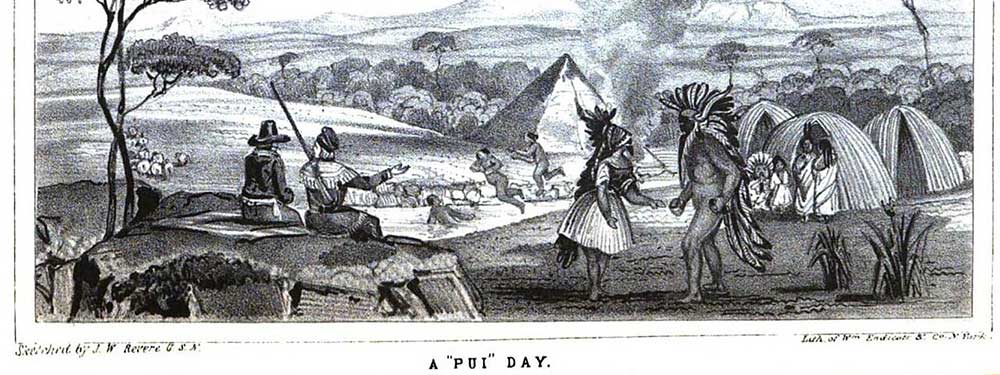

California’s Indigenous population was one of the densest and most varied in the world before colonization. Hundreds of nations populated the land from coast to mountain ranges. Tribes were intricately connected to their local ecosystems and regularly managed the land by fishing, hunting, and using controlled burns. These communities thrived and sustained consistent populations well before Spanish settlers arrived, describing California as a “land blooming with peoples, languages, and cultures.”

The Spanish first arrived in California in the late 1700s and immediately began construction of missions along the coast. Missionaries moved inland to convert the Indigenous peoples to Christianity and forced them into labor, domestic servitude, and religious practices that controlled all aspects of their daily lives. Native Californians were forced to work in the fields, raise livestock, and cook and clean for Spanish soldiers. They could not leave the missions, under threat of severe punishment, and were forced to abandon their cultural practices.

In some ways, disease was more damaging to California’s Indigenous people than colonization. Spanish missionaries brought with them diseases like measles, smallpox, and influenza that Indigenous peoples had never been exposed to and had no immunity against. Clergy documented that whole towns and villages of California’s Indigenous population would “disappear as if by magic.” Within decades, anywhere from 60-80% percent of California’s Native peoples had perished.

As Native Californians were subjected to the mission system, their cultural practices began to fade. Children were pulled from their families to live at missions where they no longer spoke their native languages. Indigenous spirituality was forbidden, and practices like basket weaving and storytelling began to dwindle. Many Native Californians became dependent on the missions for their families’ survival. Murders, whippings, and overcrowding spread disease even faster.

Mexican officials began shuttering the missions and returning the land to native inhabitants in the 1830s. California’s Indigenous population had been decimated by disease, displacement, and destruction of their culture, leaving a broken people and society that would foster racial violence during the Gold Rush and beyond—the world that would create Joaquin Murrieta.

Mexican California and a Changing Frontier

Mission lands were eventually secularized by Mexican officials in the 1830s, ending their strict oversight of Native American labor and land. Mission assets were broken up and given away (frequently to Californio elites) as ranchos—massive grazing lands that transformed California from a region of crop cultivation to one of cattle grazing. Indigenous peoples were seldom given the lands they had been promised, but many found work as vaqueros on these ranchos, forced into a new social hierarchy if they wanted to eat.

California ran itself under Mexican governance because it was so far from Mexico City, and officials allowed local governments to self-regulate. Californio families and regional customs dominated day-to-day life in Mexican California at a much slower pace than most people were used to in the States. Life focused on cattle ranching, trading with ships, and the ebb and flow of seasonal living. Mexico allowed California to basically do as it pleased, and many foreigners who visited commented on how independent the province was. One foreign diplomat even stated that California was “a country apart, ruled more by habit than by law.”

Mexican-controlled California continued to face pressure from outside visitors and traders, particularly those from the United States. American commercial ships continued to visit California, selling goods and trading with Mexicans. American trappers and settlers also began arriving in California in the 1830s and 1840s, some illegally, but others simply allowed because of lax law enforcement. Tensions rose as more Americans settled in Mexican-controlled California. They were viewed with suspicion by Californios who worried about losing land and power to foreign settlers.

Californios were frequently frustrated by what they saw as disrespectful Americans who pushed their way into Mexican land, took what they wanted, and demanded rights and representation in local government. Race and cultural differences heightened tensions on both sides. Mexicans resented the Americans for being too pushy and not respecting Mexican law, while Americans thought Mexican officials were crooked and did not have jurisdiction over the land. Violence, ranging from small skirmishes to intimidation and even assassination attempts, flared up around the border towns.

The American Takeover and Gold Rush Chaos

The region changed almost overnight with the United States’ conquest of California during the Mexican–American War. American troops began occupying the major settlements in 1846 and ended Mexican rule two years later with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which promised citizenship and property rights to Californios living there. But these promises would be routinely ignored, as courts, language barriers, and outright violence began stripping Mexicans of their lands within just a few years.

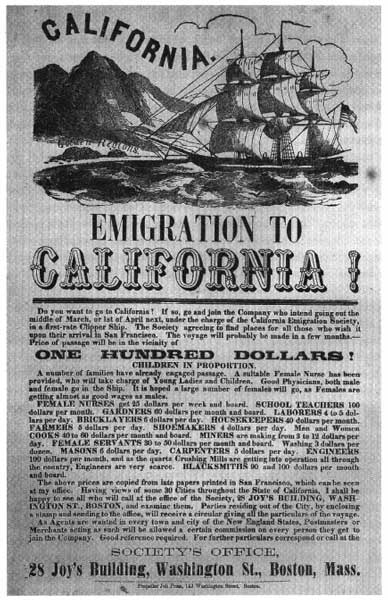

These conflicts escalated with the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in 1848. Word spread around the world within months, and hundreds of thousands of prospectors arrived from Latin America, Europe, China, and the United States. Towns emerged seemingly overnight and were described by one miner as “a chaos of tongues, tents, and tempers.” Law and order were scarce, and races were often held to determine who was fit to stay.

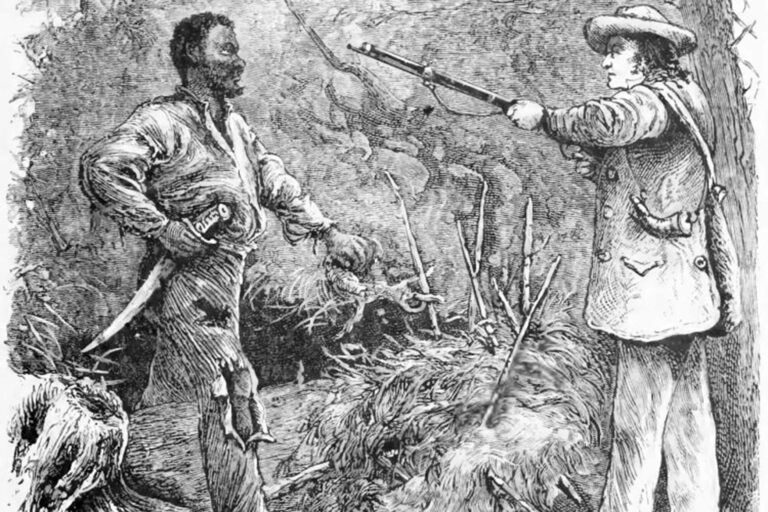

In mining towns where few formal institutions existed, vigilantism became the norm. Lynch law replaced the courts, with mobs serving as judge, jury, and executioner. Violence of all kinds was considered routine against anyone who opposed the pursuit of gold. Lynchings, beatings, and summary expulsions were used to maintain order in the mines.

Mexican and Native miners were frequent targets of this violence. Foreign miners’ taxes were passed mainly to target Mexicans and Latin Americans. Native people were hunted out of their own land or forced into slavery. Newspapers didn’t even try to hide their biases toward Mexicans, publishing articles such as: “They have no rights that a White man is bound to respect.” In such an environment, racialized hatred was commonplace.

Heroes and villains were created out of these kinds of folk tales and violence. For many Mexicans who resisted displacement, fighting back was the only solution that made sense. In this context, Joaquin Murrieta was either a ruthless criminal or a defender of the people.

The Life of Joaquin Murrieta

Joaquin Murrieta was born into a world already marked by violence and dispossession. Born sometime around 1830 in Sonora, Mexico, according to some historians, but others trace his family lineage deeper into Alta California prior to that date. Most historians have pieced together his past from oral history, court transcripts, and later dime-novel embellishments. Oral histories give us a picture of a young Joaquin Murrieta entering California during the Gold Rush years, expecting freedom and prosperity, only to face persecution.

The earliest accounts from American sources describe Murrieta as a miner and horse trader, trying to earn an honest living. Instead, he faced virulent racial prejudice directed at Mexicans following the American conquest of California. Newspapers of the day documented Mexican miners being beaten, robbed, and chased away from mining claims. One early court document alleged Murrieta was “driven from the diggings at the point of a knife,” claiming a common sentiment felt by Mexican miners. Murrieta quickly became embittered by his treatment at the hands of American settlers.

Murrieta’s life changed course when his family was allegedly murdered by Americans. Numerous accounts tell of Joaquin Murrieta losing his brother and wife to assault and murder by Anglo miners or vigilante committees. While there are several variations on which family member was murdered, most primary sources agree that Murrieta had lost someone close to him by the early 1850s. It was then that Murrieta allegedly left mining and entered into a life of crime in the American West.

Murrieta became associated with robberies, stagecoach attacks, and assaults in the mining areas of California, as well as cattle ranches throughout Northern California around the early 1850s. Murrieta was said to ride with small bands of fellow outlaws, harassing strangers and striking quickly in places well-known to his parties. Murrieta usually preyed upon Anglo miners, ranchers, and stagecoach companies, which were often interpreted by Mexican-Californians as Anglo institutions. Some Mexicans during this time even saw Murrieta’s actions as revenge against American settlers.

Joaquin Murrieta and his gang began rustling horses and attacking travelers along stock trails. Soon, they were attacking isolated mining camps and robbing along the Sacramento River. American newspaper accounts portrayed Murrieta as a murderous bandit, while Spanish-language accounts viewed Murrieta as righteous. A collection of reports by California Rangers noted that Murrieta “moves like a ghost through the valleys.” Murrieta became infamous for his ability to attack outlying communities and then disappear back into the wilderness.

Murrieta soon became more than one man. Crimes were attributed to Murrieta when his involvement was questionable, or when outlaws used his name. Joaquin Murrieta was growing in notoriety and becoming harder to find. The lines between myth and reality were quickly blurred as state authorities struggled to control the violence.

Outlaw or Folk Hero?

Joaquin Murrieta came to be accused of leading murderous assaults against Anglo miners, ranchers, and other California residents. Reportedly attacking mining camps with knives and guns, stealing horses and money, and killing people arbitrarily, created terror throughout the Gold Rush region. To many California settlers and miners, Murrieta represented frontier injustice personified during a period of rapid immigration and an inadequate legal system. California judicial and law enforcement officials characterized Murrieta and his gang as criminals and common thieves.

Others say that Murrieta escalated from stealing to murdering in retaliation against the brutal treatment of his family and fellow Hispanics by local vigilantes, criminal Hispanics, and racially biased courts. These stories allege vigilantes whipped Murrieta, drove his family from their property, or killed his wife and brother.

His retaliatory rampages were racially motivated due to the injustices inflicted against him and other Mexicans living in California during the Gold Rush period. It is unclear whether Murrieta formed an organized guerrilla resistance movement against the American settlers or merely sought revenge against those who crossed his path.

A legend comparing Joaquin Murrieta to Robin Hood surfaced much later in Mexico and among Californios. These stories often tell of Murrieta robbing from the rich to give to the poor or passing up opportunities to rob poor farmers. While there are stories supporting this claim, there is little evidence that Murrieta was consciously redistributing wealth to the poor.

The California Rangers and the Manhunt

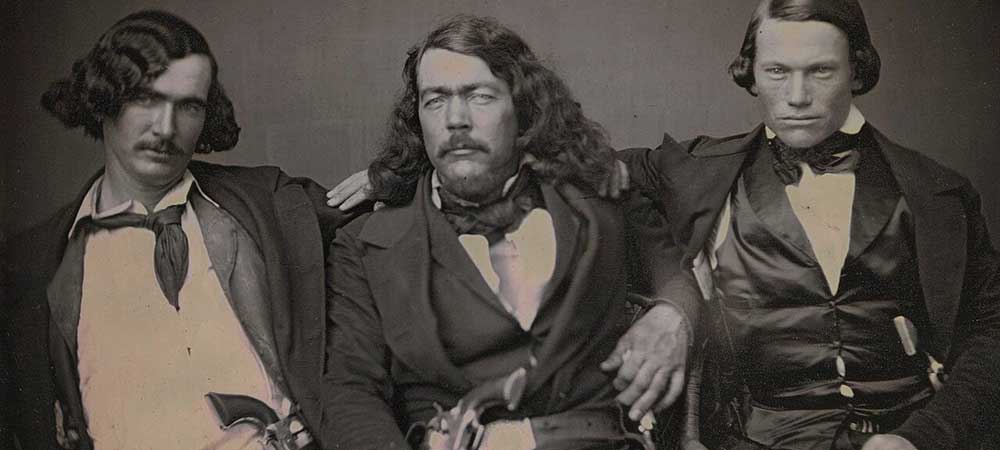

The California State Legislature chartered a posse to pursue these criminals in 1853. Captain Harry Love and his California Rangers were sanctioned by Governor John Bigler to become an official state-mounted militia with near-limitless powers. The primary objective of Love and his Rangers became focused on capturing or killing Joaquin Murrieta and his gang. Anglo-American outrage over violence on the frontier was reaching a fever pitch.

The Rangers were given free rein over the mining camps and ranch lands of California. They traveled fast and far, gathering information from sources, threats, and ambushes. Due process for alleged criminals was minimal at best. Anyone who looked suspicious was shot on sight, and few arrests were made. Violence from lawmen and violence from criminals became dangerously synonymous.

Deaths without trial became par for the course during the manhunt for Murrieta. Many men were killed at the hands of the California Rangers and claimed to be Murrieta’s partner in crime. Murrieta remained at large, however, perpetuating fear throughout Mexican and Native Towns alike. Not only were these groups victimized by crime on the frontier, but they also feared the state militia. Anti-Californio sentiment was rampant among American civilians who had recently settled in the state.

By July of 1853, the California Rangers claimed to have killed Murrieta and his second-in-command, Juancho Richard, also known as Three-Fingered Jack. According to their testimonies, Murrieta’s men surrounded them by the Arroyo Cantua, near Yeager Pass. In the ensuing gunfight, which lasted only a few minutes, both Murrieta and Three-Fingered Jack were killed. Suspiciously, the body of Joaquin Murrieta was killed just weeks before the California Rangers’ paid contract was set to expire. Upon his death, the men were paid and assured fame and celebrity.

In order to confirm the death of Joaquin Murrieta, the head of the slain body was cut off and preserved in alcohol, as was Jack’s hand. The bodies were paraded across towns in California, and people were charged admission to see the carnage. The head of Joaquin Murrieta became a sideshow attraction as the California Rangers toured the state, cementing state-sanctioned violence into brutal entertainment.

Some questioned the identity of the body. Murrieta had eluded one of the largest manhunts in American history, and some spectators claimed the body was not Murrieta’s. The judge who investigated the death of Murrieta even said it was impossible to know for sure. However, the show must go on. People came to see the head, and California Rangers rode off into the sunset.

Mythmaking and Cultural Memory

Joaquin Murrieta’s legend didn’t die with him, even after he supposedly died in 1853. Right after his death, newspapers began twisting his tale with pamphlets and rumors, continuing the trend. Part of what fueled the myth was uncertainty about Murrieta’s death. Did he really die that day? News traveled slowly in California, and tall tales spread quickly.

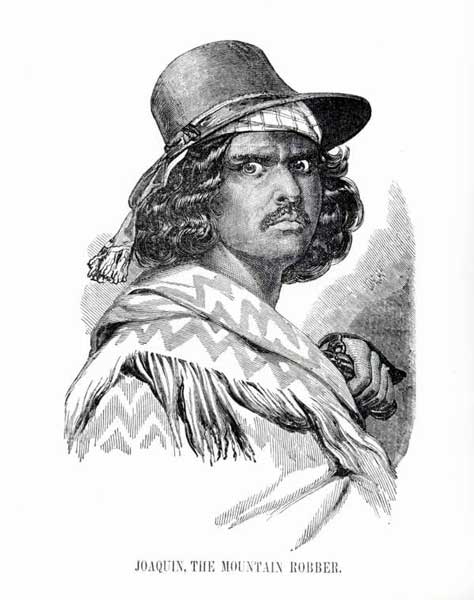

Murrieta became the subject of dime novels, sensational stories printed on cheap paper that were passed around for years. Writers exaggerated his story beyond recognition, giving him heroic speeches and framing his murders as punishment for injustice. They wrote of him early on as “the terror of the oppressor and the hope of the oppressed.”

Murrieta himself faded into fiction, morphing into whatever the audience needed him to be. Depending on who was telling the story, Murrieta was either a brutal murderer or a symbol of Mexican pride in the face of racist atrocities. Stories exaggerated his skill as a swordsman and robber, often mentioning legendary escapes from near-certain death.

Murrieta’s family even added intrigue, claiming he never died. They stated that Murrieta was not killed in that ambush and that the head shown by the California Rangers belonged to someone else. Murrieta’s family said that the Rangers picked a head to swap with theirs so they could keep the reward money and continue oppressing Mexicans.

After death, Murrieta’s head became an attraction. Exhibited for decades after his death and pickled in alcohol, his head toured Northern California in exchange for a small admission fee. The bounty became a spectacle, objectifying Joaquin Murrieta and firmly cementing him in the public imagination.

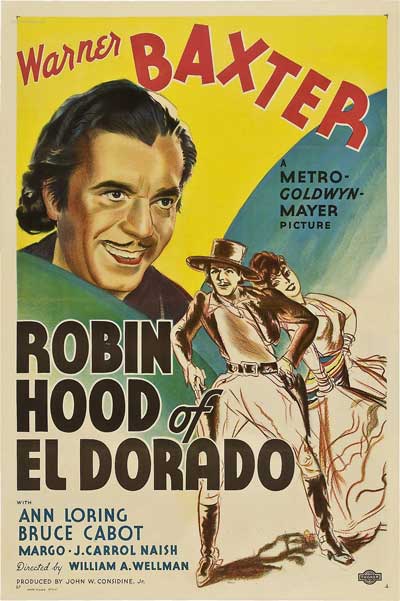

Over time, Murrieta evolved into something of a Robin Hood figure. Whether he robbed from the rich to give to the poor was secondary to what he symbolized to those who were suffering. Murrieta became the voice of those who had been violently displaced by conquest and were shut out of participating in the Gold Rush economy.

Murrieta influenced others as his legend grew. Authors have cited Murrieta as an inspiration when creating masked bandits of fiction, characters who target corrupt authority figures and fight for the common person. The most notable of these is the character Zorro, with similarities ranging from mannerisms to motivations.

The legend of Joaquin Murrieta outgrew the facts of his life. Rumors about his death, denials from his family, exaggeration by authors, and public exhibitions transformed Murrieta into folklore. Much like the life of Joaquin Murrieta, the legend is impossible to prove was real or not.

Reassessing Joaquin Murrieta

Historians today are far more skeptical than nineteenth-century writers about Joaquin Murrieta. We know that the sources available to us are partial, hostile, and/or inflated for dramatic effect. Little court documentation remains; the newspapers were not his friends, and forty years of fiction swamped the historical record. Modern historians focus less on verifying each element of the story and more on piecing together the context out of which the legend developed.

Some historians locate Murrieta in the racial violence that emerged in California following the U.S. takeover of the territory. Mexicans and Californios were forced to pay special taxes, were prohibited from holding mining claims, and suffered frequent assaults. Several historians suggest that Murrieta’s crimes- real or embellished beyond recognition – were a product of the enormous pressures Mexicans faced during this period. In this interpretation, Murrieta was more a product of his circumstances than a simple villain.

Other historians have reminded us that Murrieta was also reported to have robbed and killed during his criminal activities, including the robbery and killing of innocent civilians. In this telling, Murrieta could have been both a victim of racial violence and yet also a perpetrator of violence himself. While difficult to reconcile with the popular mythology, this more nuanced interpretation may be closer to the truth.

Perhaps asking if Murrieta was a criminal or a resistor is the wrong question. In Gold Rush California, lawful authority was capricious at best, and justice was hardly blind. Violence frequently substituted itself for the law. As such, the boundaries between outlawry and resistance were often blurred.

What we know about Joaquin Murrieta tells us less about him and more about the ugly realities of life during the Gold Rush. Behind the shiny rocks were stories of conquest, dispossession, and racialized social hierarchy. Murrieta’s legend reveals how easily fact can be replaced with myth when we would rather have legends than memories.

Violence, Memory, and Identity

The world Joaquin Murrieta was born into was defined by conquest, by racial exclusion, by sudden violence, and dispossession. Murrieta himself was made by California’s occupation by U.S. settlers and the madness of the Gold Rush that followed—when lawlessness was common, and justice was meted out unevenly at best. In those times, there was potential for men like Joaquin Murrieta to be made in a matter of days.

But there’s another way to look at Joaquin Murrieta: as a cautionary tale about glorifying violence. Resistance is powerful, but we shouldn’t celebrate bloodshed and mayhem. Myths like Joaquin Murrieta’s erase the true pain and brutality on both sides.

Murrieta lives on because the conversation about him forces us to reckon with how history gets written. Who gets to tell their side of the story? How do those in power manipulate the historical record? American history gets harder, but also richer when we remember Joaquin Murrieta. Whiteness, justice, and history aren’t created in conversation—often they’re created through violence.