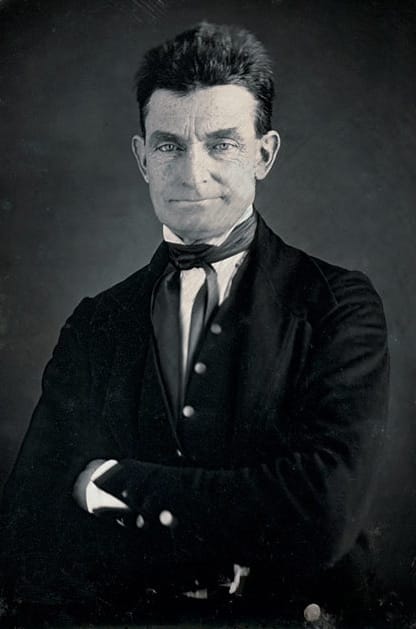

John Brown: The Abolitionist Who Sparked a Nation’s Crisis

John Brown was a radical abolitionist who believed in the violent overthrow of slavery. He came to prominence with his raid on Harpers Ferry, a federal armory, in 1859. He hoped to use the weapons from the armory to start a slave rebellion, but was captured and killed by troops. His actions and subsequent trial further inflamed the already tense relationship between the North and South, and he became a martyr for the abolitionist cause. To the South, Brown was a radical terrorist, but to the North, he was a hero who stood up against the immoral institution of slavery.

John Brown’s Early Life and Formative Years

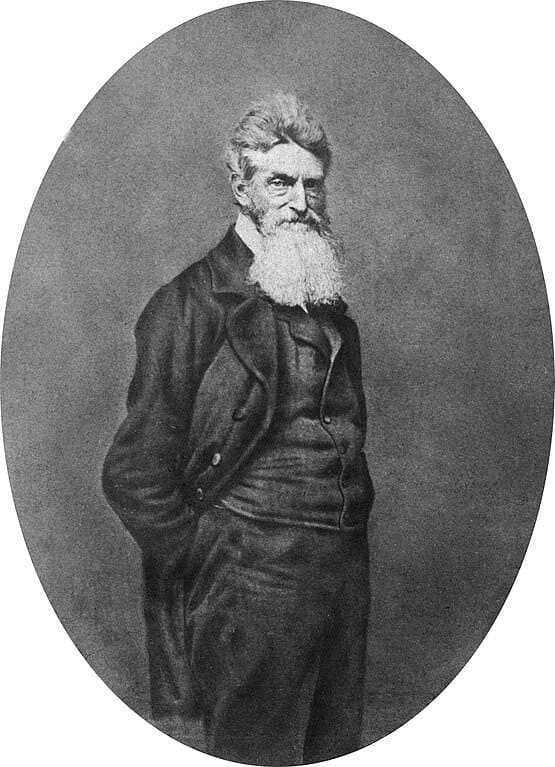

John Brown was born on May 9th, 1800, in Torrington, Connecticut, to a highly religious family that was against slavery. His father was a tannery owner named Owen Brown, a devout Calvinist. He would ensure that his son John grew up to be a virtuous, moral, and just man. His family was against slavery on the grounds of religion; it was simply a sin to enslave another person. His first encounters with slavery left an early impact on Brown’s conscience. As a child, he was able to see the true atrocity of slavery and the damage it caused to its victims.

He spent his childhood moving with his family to Hudson, Ohio. This was in a part of the country with rapidly increasing abolitionist sentiment. He would have been surrounded by conversations that dealt with the moral and political implications that the existence of slavery brought.

He was also an avid reader, mainly of religious texts that emphasized justice and liberation. He was also able to see the psychological damage that slavery inflicted on the enslaved person.

These readings and discussions no doubt left a significant impression on young John Brown, and these early experiences turned his mind toward viewing abolition not only as a political necessity but also as a religious and moral obligation. His early experiences convinced him that abolition would not be achieved through peaceful protest and negotiation.

Brown’s first jobs were tanner, farmer, and businessman, but most of his business efforts failed and he was constantly in need of money. During these years, he became increasingly active in the abolitionist movement, aiding the Underground Railroad and serving as a safe house for runaway slaves. In 1837, abolitionist newspaper editor Elijah Lovejoy was killed by a pro-slavery mob. Lovejoy’s death turned Brown toward violence and convinced him that change would not be achieved without it.

In the 1840s, Brown became increasingly sure that God was leading him to battle in a “crusade against slavery”, and that he had been divinely chosen to bring about its end. During his early years, Brown had his first experiences with slaves, as well as with several abolitionist leaders. He came to believe that a bloody conflict would be necessary to end slavery. These early life events and encounters set the stage for his participation in Bleeding Kansas and the Harpers Ferry raid.

Activism and the Bleeding Kansas Conflict

John Brown’s militant abolitionist actions reached new heights during the mid-1850s, a period known as Bleeding Kansas, when he became actively involved in the violent conflict between pro-slavery and anti-slavery settlers. Bleeding Kansas erupted after the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 allowed residents of Kansas to decide the issue of slavery through popular sovereignty. As both abolitionists and pro-slavery settlers flooded into Kansas, the region became a testing ground for the future of slavery in the United States. John Brown arrived in Kansas in 1855 with five of his sons. He began preparing for violent conflict, determined to defend the anti-slavery cause and protect abolitionist settlers from pro-slavery aggression.

The Pottawatomie Massacre of May 1856 was a critical turning point in John Brown’s use of violence. In response to the sacking of the abolitionist town of Lawrence, Kansas, by pro-slavery forces, Brown led a small group of men on a night raid along Pottawatomie Creek. The group brutally killed five pro-slavery settlers whom Brown and his followers viewed as aggressive proponents of slavery. The massacre horrified the nation and intensified the violence in Kansas, further polarizing the region. While many abolitionists condemned Brown’s actions, the event underscored his belief that the destruction of slavery would require uncompromising and often violent action.

John Brown’s participation in the Battle of Osawatomie later that year further solidified his image as a militant abolitionist. When a pro-slavery force attacked the town of Osawatomie, Brown and a small group of defenders fought fiercely, although ultimately unsuccessfully, against the attackers. Although the town was burned, Brown’s leadership and bravery in the face of overwhelming odds won him the nickname “Osawatomie Brown” and further elevated his status among radical abolitionists. For Brown, the Battle of Osawatomie represented a symbolic stand against the expansion of slavery and a personal validation of his belief in the necessity of armed resistance.

Brown’s experiences in Bleeding Kansas had a profound impact on his approach to the abolitionist cause. The violence and bloodshed in Kansas convinced him that slavery could not be abolished through legislative compromise or peaceful means. By the time he left Kansas, John Brown had fully embraced the idea of leading a larger, more organized insurrection against slavery. His experiences during Bleeding Kansas laid the groundwork for his plan to raid Harpers Ferry in an attempt to incite a nationwide slave uprising. Bleeding Kansas transformed John Brown from a regional anti-slavery activist into a national figure, setting the stage for his dramatic and ultimately controversial final act.

Planning the Harpers Ferry Raid

John Brown’s plan for Harpers Ferry was motivated by his belief that slavery could be abolished only by force. In the late 1850s, Brown conceived a strategy to incite a massive slave revolt that would start in Virginia and spread throughout the South. He planned to lead a group of men to capture a federal armory in Harpers Ferry and distribute its weapons to the slaves, igniting a rebellion that would overthrow slavery. Brown worked on this plan for several years, during which he garnered support from radical abolitionists and secured financial backing from influential individuals, including members of the Secret Six, a group of wealthy Northern supporters.

In 1858, Brown held a secret meeting in Chatham, Ontario, where he shared his plans and drafted a provisional constitution for the free republic he aimed to establish. He sought to create a network of liberated communities in the Appalachian Mountains that would provide refuge for escaping slaves. The meeting was marked by Brown’s attention to detail and idealism, as he meticulously outlined his military and logistical plans. However, despite his thorough preparation, the plan had flaws. Brown struggled to recruit enough men for the raid, and delays in acquiring weapons added to the uncertainty about the mission’s success.

In the summer of 1859, Brown and his small group of about 21 men, including his sons and several free Black volunteers, established a base at a rented farmhouse near Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia). From there, they secretly stockpiled weapons and finalized their plans for the attack. Brown’s reliance on secrecy and the element of surprise was a crucial component of the plan, but it also left him isolated and without broader support. He hoped that once the raid began, slaves in the surrounding areas would join the rebellion, bolstering his forces and ensuring victory. This expectation would prove to be a significant miscalculation.

As the raid approached, Brown remained resolute despite growing doubts from some of his followers. His strong convictions and belief in the righteousness of his cause clouded his judgment about the risks posed by limited manpower and coordination. The raid, which took place on October 16, 1859, would become a turning point in American history. Although the plan itself was flawed, the political and symbolic ramifications of the raid far exceeded Brown’s initial expectations, solidifying his place as one of the most controversial figures in the fight against slavery.

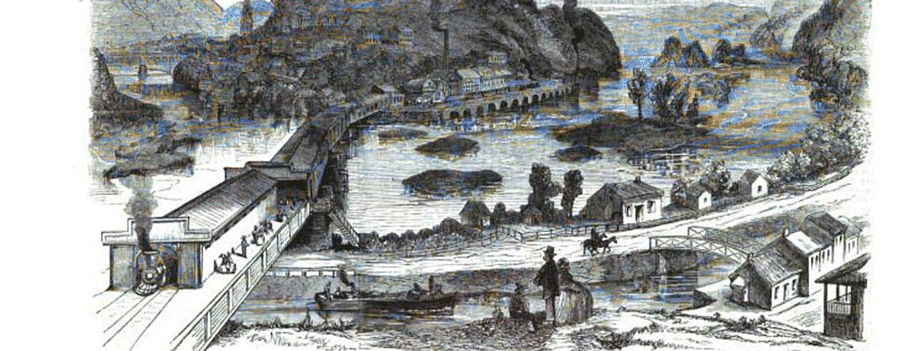

The Raid on Harpers Ferry

On the night of October 16, 1859, John Brown and a small group of followers launched their audacious attack on Harpers Ferry. The raid started well, with Brown’s men taking control of the armory, a nearby rifle works, and several hostages, including Colonel Lewis Washington, a relative of the first president. However, as the morning of October 17th dawned, the carefully constructed facade began to crumble.

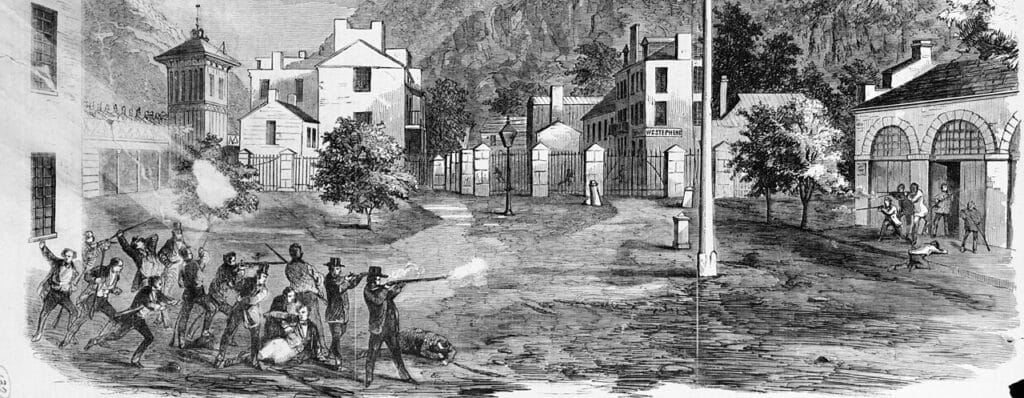

Word of the raid had reached the townspeople, who sounded the alarm. By mid-morning, armed civilians and elements of the local militia surrounded the armory, effectively cutting off Brown’s escape routes. The element of surprise that had so favored Brown in the early hours of the attack was lost, and the town of Harpers Ferry became a trap for the incensed intruders. Brown and his men retreated to the armory’s fireproof magazine, a building designed to store weapons and ammunition.

Brown’s seizure of the armory initially had a significant military impact. His strategic capture of weapons and resources, along with his attempt to incite a larger slave uprising, demonstrated a direct challenge to the institution of slavery. However, as the day progressed, the raid’s momentum was lost. The local population, which Brown had expected would rise in support, instead mobilized against him. Brown had grossly underestimated the number of local slaves willing to join his cause, and this, coupled with his tactical isolation, left him soon outnumbered.

The raid’s turning point came on October 18 when U.S. Marines, under the command of Colonel Robert E. Lee, were dispatched to quell the insurrection. After a brief but violent confrontation, Brown and his remaining men were captured or killed. Brown himself was wounded during the assault but, by a remarkable stroke of luck, survived to stand trial. The raid on Harpers Ferry, a bold and shocking attack on the institution of slavery, ended not with the emancipation of a significant number of slaves but with the capture and trial of its leader.

John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry had a profound and lasting impact on the United States. It was a catalyst that accelerated the nation’s slide into the Civil War. The raid heightened Southern fears of slave insurrections and convinced many Southerners that their way of life was under attack by the North. In the North, Brown became a controversial figure, a martyr for some and a terrorist for others. His raid on Harpers Ferry inflamed an already volatile national debate over slavery, secession, and states’ rights, and pushed the nation closer to the brink of war.

Trial and Execution of John Brown

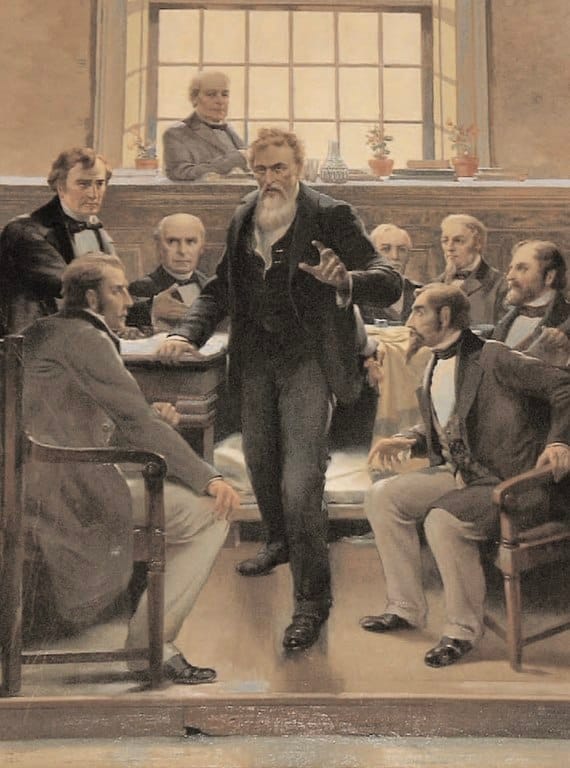

Brown was tried for treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia, for murder, and for inciting slaves to insurrection. His trial began in October 1859 in Charlestown, Virginia (now West Virginia). The trial was brief; the court received much pretrial publicity, and Brown, having been wounded during the raid, was pale and weak but spoke defiantly. The prosecution introduced testimony from some of the captured raiders and hostages to convict Brown. Brown’s lawyers tried to stall and plead for mercy, but Brown took charge of his own defense and refused to deny that he had led the raid, instead defending it on moral grounds.

The public reaction to Brown’s words in court, particularly his final speech before sentencing, gave him an iconic status among many Northerners. Brown admitted that he had intended to free the slaves with violence, and he asserted that this action was the moral duty of every American. He also declared that he was willing to die for the cause of ending slavery. He quoted both the Bible and the legal system during his speech, and appeared calm and pious, even as he was going to be executed for his crimes.

Southerners saw Brown as a criminal and terrorist, but many abolitionists, writers, and intellectuals in the North were deeply moved by his bravery and willingness to die for his ideals. Brown’s speeches and his trials were reprinted in newspapers and pamphlets all over the country.

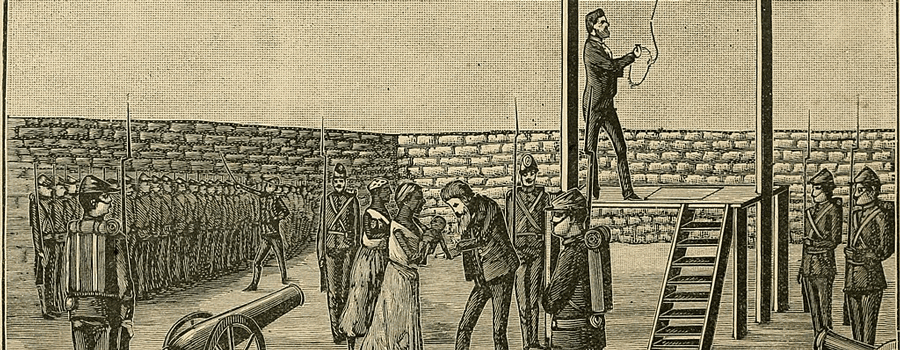

Brown was hanged on December 2, 1859. Thousands, including future Confederate General Stonewall Jackson and future actor John Wilkes Booth, came to watch the execution. He was composed, and his dignity during his final hours further endeared him to Northerners who were committed to ending slavery. Some say he walked up the steps of the gallows with determination and did not show fear as he was hung.

National Reaction and Political Fallout

John Brown’s trial and execution elicited strong and deeply divided reactions from both the North and the South. In the North, many abolitionists and intellectuals began to portray Brown as a martyr who had sacrificed his life for the cause of ending slavery.

Brown’s words during the trial, particularly his statement that he was “now quite certain that the path I have taken is the one almostI have always known to be the best,” resonated with Northern audiences and led to public mourning. Church bells tolled, memorial services were held, and poets like Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote poems and essays praising Brown’s heroism and martyrdom. For many in the North, Brown’s death was not a defeat but a call to continue the fight for abolition.

In the South, the response to Brown’s execution was one of fear and outrage. Southerners were shocked and terrified by the raid on Harpers Ferry and believed that it revealed the true intentions of the North to foment slave uprisings. The fact that Brown had support from prominent Northern abolitionists like Thoreau and Emerson only confirmed Southern fears that the North was actively working to destroy their way of life. Southern leaders called for increased security measures and greater efforts to suppress abolitionist activity. The fear of future attacks and insurrections led to increased calls for secession, with many Southerners arguing that it was better to leave the Union than to remain vulnerable to such threats.

Brown’s raid and execution hardened divisions between the North and the South and made compromise increasingly difficult. Brown’s actions confirmed for many Southerners that coexistence with the North was impossible. At the same time, Northern abolitionists saw his martyrdom as proof that peaceful means would not be enough to end slavery. The raid intensified the existing tensions over issues such as state rights, territorial expansion, and the enforcement of fugitive slave laws. The growing mistrust between the regions would eventually lead to the outbreak of the Civil War, with Brown’s death accelerating the national slide towards conflict.

By the time the Civil War began in 1861, Brown had become a symbol for both the Union and the Confederacy. His raid on Harpers Ferry may have been a military failure, but its political impact had a lasting effect on the national debate over slavery. Brown’s martyrdom had galvanized the abolitionist movement and made him a lasting symbol of the fight for freedom and justice.

Legacy and Historical Debate

John Brown is an inordinately polarizing historical character, spawning an avalanche of heated discourse among historians, scholars, and the general public alike. On the one hand, Brown has been perceived as a freedom fighter and martyr who sacrificed his life for the noble cause of eradicating the country’s most heinous form of inhumanity, and thus represented the best of the human race.

Furthermore, he was willing to act, go all in, and not shirk his duty when it came to freeing other people from bondage. On the other hand, John Brown was a bloody terrorist; someone who crossed the line of conventional morality and took his radicalism too far. While the question of whether his actions were warranted or not is left for the reader to decide, it is safe to say that his raid on Harper’s Ferry became a catalyst for the emancipation of the enslaved.

The legacy of John Brown lives on long after his death, and in the 20th century, figures like W.E.B. Du Bois and Martin Luther King Jr. discussed Brown and his role in the fight for civil rights for Black people in the United States. King, for example, did not agree with Brown’s violent methods, but he did see the fervor and moral righteousness behind Brown’s cause, even if he did not endorse his chosen tactics.

Brown’s story is still represented in the black communities as a symbol of resistance and the importance of fighting back against systems of oppression. In literature, in art, and in public memory, the story of John Brown has been memorialized and continues to be told long after his death.

In the end, the legacy of John Brown is one of both inspiration and controversy. His life and death pose questions that are still being asked today about the use of violence to fight for justice, and the line between heroism and terrorism.

For some, he is a tragic hero who died for a cause, but for others, he is a villain, a madman, a murderer who should not be revered. In either case, Brown was a hugely important figure in American history, and his name will live on for centuries to come.

![[Video] Today in History: From the Pullman Strike to Labor Day](https://historychronicler.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Screenshot-2025-09-02-at-1.15.28-PM-768x512.jpg)

![[Video] John Paul Jones and the Battle of Serapis 9.23.1779](https://historychronicler.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Screenshot-2025-09-23-at-12.34.22-PM-768x512.jpg)