Roman Decimation: The Grim Reality of Blood on the Standards

Throughout military history, few practices strike as deep a chord of dread as the Roman decimation method. Decimation was a ruthless disciplinary action, a dark and bloody chapter that underscored the iron resolve of Roman military command. Decimation was not merely a punishment but a stark testament to the lengths the Roman Army would go to maintain order, discipline, and fear among its ranks.

The Roman Army, renowned for its formidable structure and tactical prowess, was notorious for its stringent disciplinary methods. Among these, decimation stood out for its sheer brutality and psychological impact. As a cursory look reveals, Roman discipline extended beyond mere drills and strict regimentation; it encompassed a range of punitive measures, each designed to instill unwavering loyalty and immediate obedience.

From flogging and fines to the terrifying act of decimation, the Roman military machine operated under a regime where the cost of disobedience could be as high as life itself. This introduction sets the stage to explore how, under the shadow of such severe consequences, the Roman legions carved out an empire that would echo through the ages.

The Harrowing Practice of Decimation

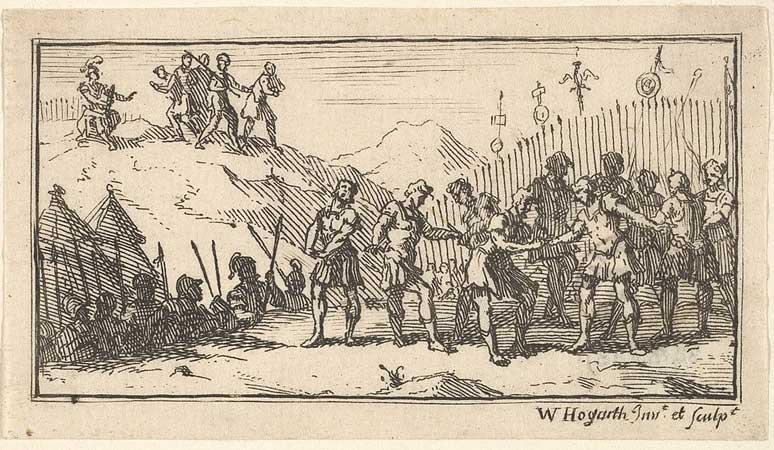

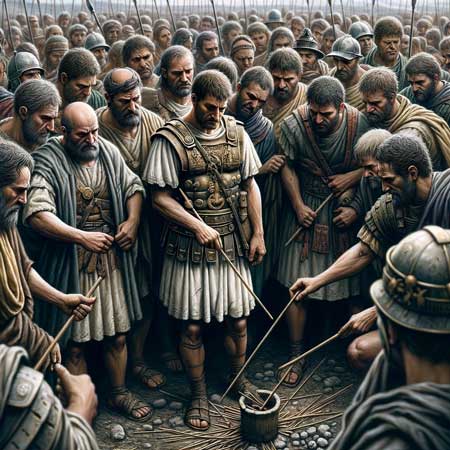

Decimation, from the Latin ‘decimatio,’ meaning ‘removal of a tenth,’ was a disciplinary method as brutal as simple. In its most traditional form, it was employed by the Roman Army to punish units or large groups guilty of serious misdemeanors such as mutiny, desertion, or cowardice. The process involved dividing the men into groups of ten; each group would draw lots, and the soldier who drew the short straw was executed by his nine comrades, usually by clubbing, stoning, or stabbing. This severe punishment was intended not just to eliminate the weak but also to serve as a harrowing lesson to the survivors, searing into their minds the dire consequences of disobedience and disloyalty.

The psychological impact of decimation on Roman soldiers was profound. It instilled a pervasive fear that ensured discipline, but at the same time, it fostered a deep sense of unity and responsibility among the troops. The knowledge that one’s fate could be so closely tied to the actions of fellow soldiers meant that peer pressure became a powerful force for maintaining order. Soldiers knew their survival might depend as much on the man next to them as on their courage and discipline. This collective accountability was crucial in an army where maintaining cohesion and morale over vast distances and long campaigns was essential.

Nevertheless, the use of decimation varied over time and from commander to commander. While some saw it as an essential tool for maintaining strict discipline, others used it sparingly, aware of its potential to breed resentment and despair among the troops. Notable commanders like Julius Caesar were known to avoid such extreme measures, preferring other methods of discipline that preserved the fighting spirit of his men.

However, the message was clear when decimation was employed: the Roman military machine would tolerate neither failure nor disobedience. As we delve deeper into the instances and repercussions of this grim practice, it becomes evident that decimation was more than just a punishment; it reflected the Roman military ethos, one where the standards of discipline and the weight of consequence were as formidable as the legions themselves.

The Dawn of Dread: The First Recorded Decimation

The earliest documented instance of decimation harks back to a tumultuous period in 471 BC, during the infancy of the Roman Republic. This era was marked by relentless wars against neighboring tribes and states, including the Volsci, a formidable adversary frequently clashing with Roman forces. The practice of decimation was recorded by the historian Livy, who provided a chilling account of its use under the command of Consul Appius Claudius Sabinus Regillensis. The incident followed a particularly disastrous encounter with the Volsci, where Roman forces were scattered in a humiliating defeat.

In the aftermath of this battle, Consul Appius Claudius, determined to restore order and discipline, resorted to the most severe punishment. Centurions, standard-bearers, and soldiers accused of desertion or casting away their weapons in the face of the enemy were singled out for individual punishment. They were scourged and beheaded, a direct and brutal message to all ranks of the Army. However, the retribution did not end there. One in ten of the remaining soldiers was chosen by lot and executed.

This early instance of decimation was not just a punitive measure but a calculated effort to instill an enduring sense of fear and discipline among the troops, a reminder that the consequences of cowardice and disorder were as severe as death itself.

This grim episode set a precedent for centuries, laying the foundational ethos of Roman military discipline. It underscored the uncompromising standards expected of Roman soldiers and the extreme lengths commanders would go to maintain order and authority. The early use of decimation also reflected the broader societal norms of the Roman Republic, where collective responsibility and the harsh enforcement of laws were seen as essential to the survival and success of the state. As the Republic grew into an empire, the legacy of this early decimation would echo through the ranks of Roman legions, a stark reminder of the heavy price of failure and disobedience.

Echoes of Severity: Notable Instances of Roman Decimation

The practice of decimation, though sporadic, left a chilling mark throughout Roman military history. One of the earliest detailed descriptions comes from the Greek historian Polybius in the early 3rd century BC. He explains the methodical and cold calculation behind the punishment: when a large group exhibited cowardice or mutiny, officers would reject outright slaughter in favor of a lottery system. Based on the offending group’s size, this system would determine a tenth of the men to be brutally bludgeoned by their comrades, reinforcing a harsh lesson in loyalty and bravery.

Perhaps one of the most famous instances of decimation occurred under the command of Alexander the Great, not a Roman himself but a figure whose military tactics greatly influenced Roman generals. He employed decimation against 6,000 men of his corps as punishment for their perceived lack of discipline and motivation. This drastic action meant restoring order and demonstrating that failure and insubordination would not be tolerated, even in the mightiest armies. The message was clear: the unity and integrity of the force were paramount, and any threat to this cohesion was met with the harshest of responses.

During the conflict with Pompey, Julius Caesar issued a threat to decimate the 9th Legion but ultimately refrained from carrying it out due to concern about how it would affect the fighting spirit of the men under his leadership. The practice saw a notable revival during the Third Servile War in 71 BC under Marcus Licinius Crassus, who was combating the slave rebellion led by Spartacus. Crassus, determined to restore discipline after a series of defeats, selected 500 men from the survivors of two legions. These men were divided and decimated, with the nine surviving members of each group forced to club their chosen comrade to death. In part, this gruesome tactic was credited for Crassus’ subsequent successes.

Even later, decimation was occasionally employed during the Roman Empire, though it became increasingly rare. Emperor Augustus in 17 BC and Emperor Galba is recorded to have used it, as well as Lucius Apronius in AD 20 after a defeat by Tacfarinas. However, as noted by the historian G.R. Watson, the practice was ultimately doomed, as professional soldiers became less likely to participate in the indiscriminate execution of their peers.

The less severe ‘centesimatio’ was introduced by Emperor Macrinus in the third century., executing every 100th man, reflecting a gradual shift in military discipline and the acknowledgment of the destructive impact of such extreme measures on troop morale and cohesion.

A Dark Revival: Decimation in the 17th century

The 17th century witnessed a grim resurgence of the ancient Roman practice of decimation, particularly noted during the chaotic and brutal period of the Thirty Years’ War. This revival was primarily driven by the desperate need for discipline and order in the ranks of armies that were increasingly difficult to control, comprised of a mix of mercenaries and conscripts. Commanders, facing the challenges of maintaining order among these diverse and often unruly troops, reverted to the draconian measures of the past, believing that the fear of such extreme punishment would keep soldiers in line and prevent the disarray that could lead to catastrophic defeat.

One stark instance occurred following the Battle of Lützen in 1632 when Von Sparr’s cuirassier regiment in Gottfried Heinrich Graf zu Pappenheim’s corps disgracefully fled the field. The imperial commander, Wallenstein, incensed by this cowardice, convened a court martial that sentenced the commanding officers and several troopers to death by beheading and hanging. The surviving members of the regiment faced a brutal decimation: one in ten was hanged, while the others were beaten, branded, and declared outlaws, their standards disgracefully burned by an executioner. This severe punishment was meant to penalize and serve as a brutal reminder of the consequences of cowardice and disorder.

Similarly, the Battle of Breitenfeld in 1642 saw the flight of Colonel Madlo’s cavalry regiment, an act of cowardice that precipitated a wider panic and contributed to a significant defeat. In the aftermath, a court-martial assembled by Leopold Wilhelm in Prague delivered a harsh sentence. The regiment was stripped of its arms and dignity, its ensigns torn to pieces, and its name erased from the imperial register. The officers were beheaded, junior officers hanged, and soldiers decimated, with the survivors disgracefully expelled from the Army.

Ninety men were executed in Rokycany, western Bohemia, in a gruesome spectacle of beheadings and hangings, their bodies a stark testament to the revived practice of decimation. The site of their mass grave, known as the Black Mound, stands as a somber reminder of this dark chapter in military history. This return to ancient, severe punishments underscores the enduring struggle for discipline and order within armies and the lengths to which leaders would go to enforce it, even reviving a practice as cruel and feared as decimation.

A Shadow Over Centuries: The Continued Practice of Decimation

Despite its ancient Roman origins, the terrifying practice of decimation reemerged as a response to the challenges of maintaining order among increasingly diverse and vast armies. However, its revival and adaptation in modern times during various conflicts reveal a darker aspect of military discipline that transcends cultures and eras.

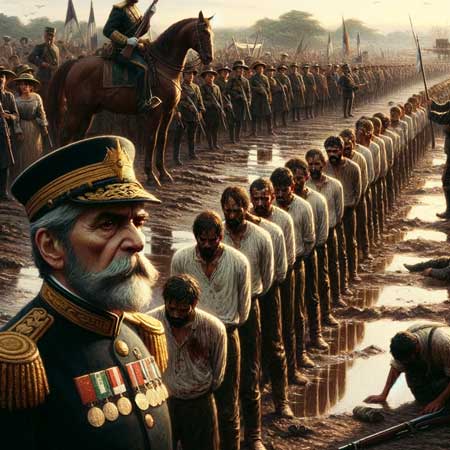

One such instance occurred during the Paraguayan War on September 3, 1866. After the 10th battalion of the Paraguayan army fled without firing a shot during the Battle of Curuzu, President Lopez, infuriated by this act of cowardice, ordered a decimation. The battalion was lined up, and every tenth man was executed by firing squad, a stark reminder of the consequences of failing to meet the harsh demands of warfare.

Similarly, in 1914, during World War I, a company of Tunisian tirailleurs in France who refused an order to attack was decimated by the divisional commander, resulting in the execution of ten men. These incidents highlight how the practice was not confined to any one region or era but was a tool of discipline and terror used across continents and centuries.

In Italy, the notorious General Luigi Cadorna is often associated with the application of decimation to underperforming units during World War I. While some accounts suggest his methods were more often individual summary executions rather than formal decimations, there was at least one confirmed instance of true decimation in the Italian Army. On May 26, 1916, a 120-strong company of the 141st Catanzaro Infantry Brigade, which had mutinied and killed officers and non-mutineers, was subjected to decimation. Ten percent of these soldiers were executed in a chilling throwback to Roman times.

This brutal practice was not limited to punishing one’s forces; it was also used against enemies. During the Finnish Civil War in 1918, after conquering the Red city of Varkaus, White troops executed about 80 captured Reds in the infamous ‘Lottery of Huruslahti,’ where every tenth prisoner was selected and shot. However, the status and actions of the prisoners influenced the selection.

Reflecting on a Legacy of Fear and Discipline

The haunting legacy of decimation, from its ancient Roman origins to its sporadic appearances in the conflicts of the 20th century, casts a long shadow over the history of military discipline and human governance. Its continued use, even in times marked by revolutionary change and a greater understanding of human rights, underscores a stark aspect of human nature: the propensity to resort to fear and brutality to maintain order and assert control. The chilling reality of decimation is not just a relic of the past, but a reminder of the depths of severity leaders might plunge to when faced with desperation and chaos.

As we reflect on the grim history of this extreme form of punishment, we must recognize the progress made in military and societal norms. Decimation is largely condemned and viewed as anathema to modern values and ethical military conduct. However, its historical recurrence is a powerful cautionary tale about the darker capabilities of military power and the constant, necessary struggle to balance discipline with humanity.

The story of decimation, with all its blood and terror, urges us to remember the past’s horrors and strive for a future where such brutal practices are never repeated, where the standards of war bear no more stains of such inhumanity. As we move forward, let the grim reality of Roman decimation and its subsequent echoes serve as a subject of historical curiosity and a solemn reminder to uphold dignity, respect, and compassion even in the face of the most significant challenges.