Rome’s Foe and Friend: The Dual Roles of Alaric the Visigoth

Alaric, the storied king of the Visigoths, is a figure etched with both infamy and complexity in the annals of Roman history. His narrative is not one of antagonism but rather a nuanced tapestry woven with threads of alliance and adversity. As the leader of a Gothic tribe that once fought alongside the Roman legions as foederati, Alaric’s initial role was that of a military ally, a staunch defender against the encroaching threats from other barbarian groups. Yet, the tides of allegiance ebbed and flowed with the political and economic currents of the late Roman Empire, eventually positioning him as one of its most formidable adversaries.

The shifting sands of Alaric’s relationship with Rome are emblematic of the era’s volatile power dynamics. His famed march towards the heart of the Empire, culminating in the sack of Rome in 410 CE, marked a pivotal moment in the decline of Rome’s centuries-long dominance. But to view him solely as Rome’s destroyer is to overlook the intricate dance of war and diplomacy that defined his interaction with the Roman state.

The Formative Years of Alaric: A Gothic Chieftain’s Emergence

In the twilight of the fourth century, along the peripheries of the Roman Empire’s vast territories, a young Alaric came of age in a region the Romans disparagingly considered a veritable “backwater.” To the ancient Roman poet Ovid, writing four centuries earlier, the lands along the Danube and the Black Sea, where Alaric spent his formative years, were the realms of “barbarians” at the edges of the civilized world. Yet, it was here, amidst these so-called barbarian lands, that the future king’s character was chiseled, framed by the ruggedness of the Balkans and the echoes of a Gothic heritage that both revered and defied the might of Rome.

Alaric’s youth was steeped in the lore and valor of Gothic warriors, particularly those who had triumphed at the Battle of Adrianople in 378. This cataclysmic encounter not only decimated the Eastern Roman army but also claimed the life of Emperor Valens. The tales of victory and bravery, recounted by grizzled veterans who had witnessed the Goths’ formidable prowess firsthand, undoubtedly kindled the flames of ambition and martial skill in the young Alaric.

The uneasy peace that followed the carnage of Adrianople was solidified by a treaty in 382, which saw the Goths, among whom Alaric was raised, granted lands within the Empire’s borders. This foedus, a first of its kind on imperial soil, transformed the Visigoths into foederati — semi-autonomous allies bound to supply troops to the Roman legions. In exchange, they received the right to cultivate fertile lands and live under their rulers, free from direct Roman administrative control.

This new accord carved out a unique niche for the Goths within the fabric of the Empire. Like many of his kin, Alaric was swept up into the ranks of the eastern field army, while others served as auxiliaries in the military campaigns of Theodosius. It was a period of transition, one in which the Goths gradually ascended from the status of foreign auxiliaries to esteemed members of the imperial aristocracy. This burgeoning relationship with the Empire paved the way for a rise through the military ranks under the tutelage of the Gothic soldier Gainas.

Alaric’s initial ventures into leadership materialized as he commanded a diverse force of Goths and allies, challenging the Roman dominance in Thrace as early as 391. Although Roman General Stilicho, himself of Vandal descent, managed to halt Alaric’s incursion, it was evident that Alaric’s leadership capabilities were burgeoning.

His presence was substantial enough to bar the celebrated Emperor Theodosius from crossing the Hebrus River, signaling the rise of a formidable force within the Empire’s frontiers. Despite the scorn of poets like Claudian, who dismissed Alaric as “a little-known menace,” his early encounters with Roman might foretold the dawn of a new era — one in which Alaric would stand not merely as a Gothic chieftain but as a pivotal figure in the annals of Rome’s storied history.

An Ambivalent Alliance: The Visigoth’s Service to Rome

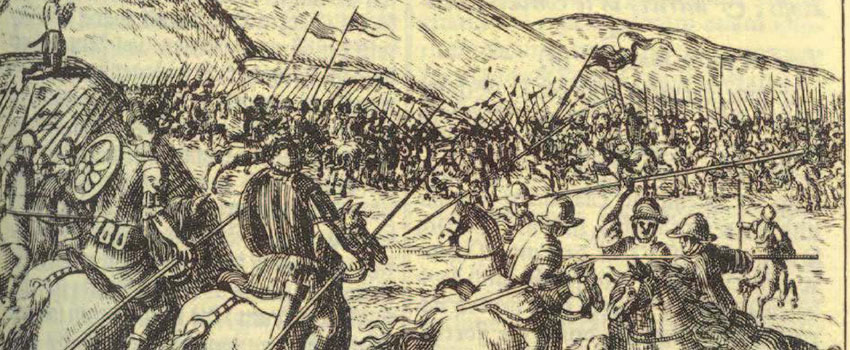

The year 392 marked a consequential turning point in Alaric’s life as he stepped into the Roman military service, which witnessed a significant thaw in the Gothic-Roman hostilities. By 394, Alaric found himself at the helm of a Gothic force in the service of Emperor Theodosius, partaking in the pivotal Battle of Frigidus. His Goths bore the brunt of the conflict, serving as the expendable vanguard against the Frankish usurper Arbogast.

The visigoth warriors were sacrificed in droves, a testament to Theodosius’ ruthless tactics to break the enemy’s front lines. Despite the Gothic blood spilled, Alaric emerged from the carnage as one of the survivors, only to find his valor and loss starkly unacknowledged by the emperor. The sight of ten thousand dead kinsmen likely sowed doubt in Alaric’s mind regarding his allegiance to Theodosius and the worth of his sacrifices.

The political landscape of the Roman Empire was irrevocably altered with Theodosius’ death on January 17, 395. The Empire, now in the hands of his inept sons Arcadius and Honorius, grappled with internal decay and external pressures. It was during this tumultuous time that Alaric, according to Peter Heather, ascended to the kingship of the Visigoths. However, the exact timing of his rise remains shrouded to history. Regardless, historian Jordanes records Alaric’s persuasive call to his people, urging them to seek a kingdom through their efforts rather than languishing in subservience.

Alaric’s ascent to power coincided with a broader Gothic awakening. The demise of Theodosius left the Roman military in disarray, and the Empire again divided. As Stilicho vied to consolidate his authority over both halves of the Empire, the Goths were forced to navigate an empire fraught with rivalries and opportunities. Roger Collins notes that although Alaric’s elevation by his people endowed him with authority, it could have done more to address their practical needs, which remained tethered to Roman support and supplies.

This necessity drove Alaric to embark on what Claudian dubbed a “pillaging campaign,” which initially found tacit support from Rufinus of the Eastern Roman regime. This foray into Greece, including the sack of Athens evidenced by archaeological damage, was an audacious attempt to renegotiate peace with Rome. Only Stilicho’s counterattack in 396 curbed the Gothic advances, driving them northward into Epirus. Yet, both Roman and Gothic campaigns left a trail of destruction, with Stilicho’s forces permitting Alaric’s troops to retreat with their spoils of war. This decision would have lasting repercussions.

The power struggles within the Empire continued to intensify. Gainas, leading his Gothic forces to Constantinople, would assassinate Rufinus and assume a pivotal military role in Thrace, reflecting the growing influence of Goths within the Roman hierarchy. Meanwhile, Alaric faced political turbulence. Stilicho, grappling with threats on multiple fronts, found his efforts to dominate the East thwarted by Gothic defiance.

In 397, as Eutropius claimed victories over Hunnic invaders and emboldened his stance, Alaric was instated as magister militum per Illyricum. This position promised sustenance and prospects of a more stable accord with Rome. This period of tranquility was short-lived, however, as the political winds shifted again in 399 with Eutropius’ fall from grace, leading to a recalibration of Alaric’s status and setting the stage for the next chapter of Gothic-Roman relations.

Alaric’s Italian Campaign: The First Incursion

In the spring of 402, Alaric set his sights on the Italian peninsula, initiating what would be known as his first invasion of Italy. The exact motives behind this bold move remain obscured in the corridors of history, with no ancient source providing a clear rationale. Historian Michael Kulikowski surmises that a desperate need for provisions might have propelled this decision.

This aligns with the insights of Thomas Burns, who suggests that the Goths were likely compelled by necessity. The onset of Alaric’s campaign, as chronicled by Guy Halsall, traces back to late 401. However, the first major confrontation with the Roman general Stilicho occurred the following year, as Stilicho was preoccupied in Raetia with matters of frontier defense.

Alaric’s path into Italy was marked by the trails outlined in Claudian’s poetry, crossing the Alpine frontier near Aquileia. For several months, the northern Italian roads felt the weight of Gothic incursions, with Alaric making his presence known to the Roman populace. It was on Via Postumia that Alaric and Stilicho first clashed. Two significant battles ensued: the first at Pollentia on Easter Sunday, where Stilicho claimed a considerable victory. Alaric’s wife and children fell into Roman hands, along with a substantial trove of Gothic treasure accrued from years of plunder.

Despite this setback, Alaric remained unbowed, and even after a second defeat at Verona, he was not conquered. Stilicho’s decision to offer a truce and permit Alaric’s retreat rather than pursue a decisive end to the Gothic threat puzzled many. Yet, as Kulikowski and Halsall note, Stilicho may have seen Alaric as a helpful instrument in his broader strategic games, particularly against Constantinople.

The complexities of the relationship between Alaric and the Roman Empire are further elucidated by a report from Zosimus, suggesting that by 405, an agreement had been struck, placing Alaric in the service of the Western Roman Empire. Alaric’s subsequent sojourn in Pannonia allowed him to leverage his position, playing the Eastern and Western Empires against each other while maintaining the potential to menace both.

The Gothic threat, however, was only temporarily assuaged. A.D. Lee points out Alaric’s departure from Italy did little to ensure long-term peace. In 405, another formidable group of barbarians, led by Radagaisus, spilled into northern Italy, ravaging the land. While Stilicho managed to deal with Radagaisus by dividing and conquering his forces near Florence, Alaric watched from Pannonia, armed with the official title of magister militum by Stilicho’s hand.

Now supplied by the West, Alaric waited, a dormant but potent force, ready to be roused into action by the changing tides of power and opportunity that characterized the late Roman Empire’s tumultuous political landscape.

Alaric’s Second Italian Campaign: A Tenuous Alliance and Its Aftermath

In the tumultuous years of 406 and 407, the Western Roman Empire faced an onslaught of challenges. The Rhine frontier collapsed under the weight of invading Vandals, Sueves, and Alans, while a rebellion under a common soldier named Constantine burgeoned in Britain and spilled into Gaul.

Amid this chaos, Alaric again set his sights on Italy, asserting his presence in Noricum and demanding an exorbitant ransom to deter a full-scale invasion. The Roman Senate, incensed by the prospect of paying tribute to a barbarian, bitterly contended that such a demand was tantamount to enslavement. Nonetheless, Stilicho, perceiving the payment to Alaric as a necessary evil given the Empire’s dire straits, acquiesced and paid the 4,000 pounds of gold.

While pragmatically forestalling immediate disaster, this concession gravely undermined Stilicho’s position within the Western Roman regime. His reputation suffered, having twice failed to deal with Alaric decisively and allowing Radagaisus to threaten Florence. The political foundation that Stilicho had so meticulously built was rapidly eroding. In the East, the death of Arcadius on May 1, 408, and the ascension of Theodosius II suggested a shift in power dynamics that Stilicho aimed to exploit. Plans to possibly integrate Alaric within the Roman hierarchy and leverage his forces against the rebels in Gaul were contemplated.

However, Stilicho’s machinations were cut short by a coup at the court of Honorius, instigated by the minister Olympius. The coup, characterized by betrayal and bloodshed, culminated in the assassination of Stilicho and the subsequent massacre of his family and Gothic federate troops by Olympius’s forces. The families of the federate troops, slaughtered as presumed allies of Stilicho, pushed the surviving soldiers into Alaric’s camp, swelling his ranks with thousands of disaffected barbarian auxiliaries.

Following these events, Alaric was proclaimed an enemy of the emperor. Deprived of the legitimacy he craved to levy taxes or secure garrisons, Alaric proposed relocating his people to Pannonia in return for a modest sum and the title of Comes. The new regime rebuffed his offer, which regarded him as an ally of the now-disgraced Stilicho. Without the support of indigenous defense forces, Italy lay vulnerable. Alaric, the once-valued Foederati leader and potential ally, found himself isolated, his relationship with the Roman court irrevocably altered, setting the stage for further confrontation and Roman ruin.

Alaric’s First Siege of Rome: Starvation and Submission

In the wake of broken promises from the Western Roman regime, Alaric, fueled by a sense of betrayal and the desperation of his troops, turned his gaze towards Rome. His army, now swelled by those who sought retribution for their slain families, numbered around 30,000. September 408 saw Alaric approach Rome, not with the sword, but with a blockade designed to starve the city into submission.

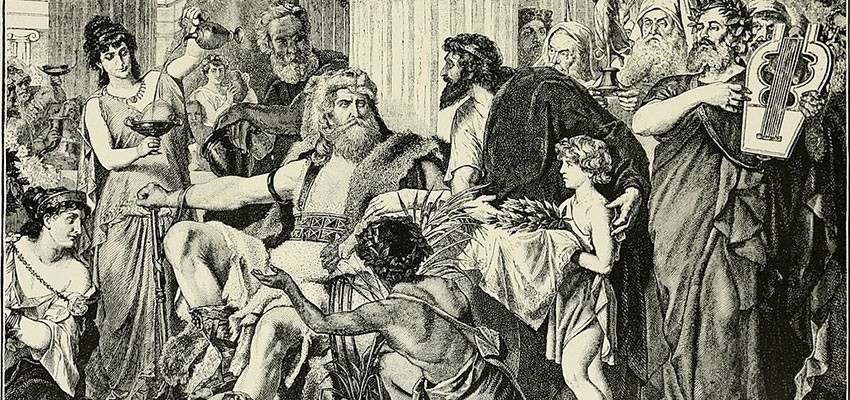

As the Roman Senate’s envoys parleyed for peace, Alaric responded to their veiled threats with confidence; he knew the city’s desperation was his strongest ally. The siege, devoid of bloodshed but heavy with hunger, led to the citizens’ acquiescence. They surrendered a ransom of precious metals and goods, a tribute that also included the emancipation and enlistment of 40,000 Gothic slaves into Alaric’s ranks. With this, the first siege ended, a testament to Alaric’s strategy and the dire straits of Rome.

The Emperor’s Recalcitrance and Alaric’s Puppet Emperor

Yet peace, it seemed, was fleeting. Emperor Honorius, ensconced in his court at Ravenna, reneged on the agreement, particularly on appointing Alaric as the head of the Roman Army—an elevation Alaric sought but was denied. In response, Alaric’s actions escalated; he laid siege to Rome once more in late 409 and took the audacious step of installing Priscus Attalus, a senator, as his puppet emperor. This new “emperor,” Attalus, out of his depth and reliant on Alaric’s favor, quickly faltered, losing crucial grain supplies from Africa and proving ineffective against Honorius’s loyal forces.

In a dramatic turn, Attalus and Alaric marched on Ravenna, extracting extraordinary concessions from a beleaguered Honorius, who was on the brink of exile. Yet, with the sudden arrival of reinforcements from Constantinople, Honorius’s stance hardened. Alaric, perhaps recognizing his miscalculation in elevating Attalus, deposed him, hoping to reset the board and renew negotiations with the fortified emperor. But the damage was done. The political landscape had changed, and Alaric found himself in an increasingly precarious position, with Rome caught between his aspirations and the resolute defiance of Honorius.

A Precarious Stalemate

The once-mighty Visigoth king, who had Rome’s gates within reach, now grappled with the complexity of imperial politics and the fickleness of military alliances. The Empire, fragmented and besieged by internal strife, still presented a formidable opponent when cornered. Alaric’s maneuverings around Rome demonstrated his capacity for war and diplomacy, his ability to wield siege, starvation, and the crowning of emperors as weapons in his arsenal. Yet, each move in this high-stakes game brought uncertain outcomes, and Alaric’s quest for recognition within the Roman hierarchy remained an elusive prize, dangling just beyond grasp.

As Alaric stood at a crossroads, his dealings with Rome had become a saga of alternating triumphs and frustrations. The promise of gold, power, and status, once seemingly secured through the might of his army and the fear he instilled, had dissipated like mist. The road ahead was fraught with challenges, yet it was clear that Alaric’s resolve had remained strong. He would continue to assert his will upon the Roman world, shaping its destiny with the force of his leadership and the indomitable spirit of his Gothic warriors.

The Final Act: Alaric’s Sack of Rome

The tenuous thread of diplomacy that once held the possibility of peace between Alaric and Honorius was decisively severed by the aggressive maneuvers of Sarus, an Amal and thus a sworn enemy of Alaric. Interpreting this as a sanctioned attack from Ravenna, Alaric had been pushed past the point of negotiation and into action. He marshaled his forces for a third siege, not to parley but to conquer.

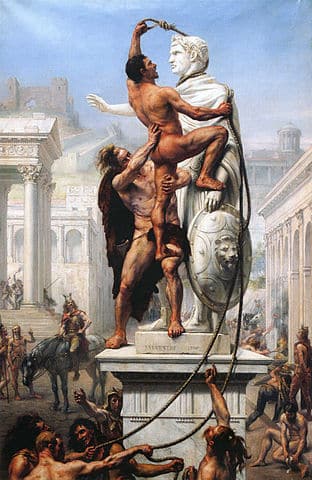

On August 24, 410, Alaric’s army descended upon Rome. The assault, which lasted three days, was marked not just by the seizing of treasures but by a significant loss of Roman life. Contemporary accounts do not provide exact numbers, but the death toll was undoubtedly in the thousands as chaos engulfed the city—many unreliable reports even put death tolls into the tens and hundreds of thousands. Roman citizens, both wealthy and common, perished at the hands of Gothic soldiers.

While precise figures on the plunder are lost to history, it is recorded that Alaric’s men extracted vast sums of wealth. The riches of Rome, accumulated over centuries through empire-building and conquest, were systematically stripped. The Visigoths looted countless artifacts, sacred relics, and untold amounts of gold and silver—treasures representing the material glory of Rome’s bygone era.

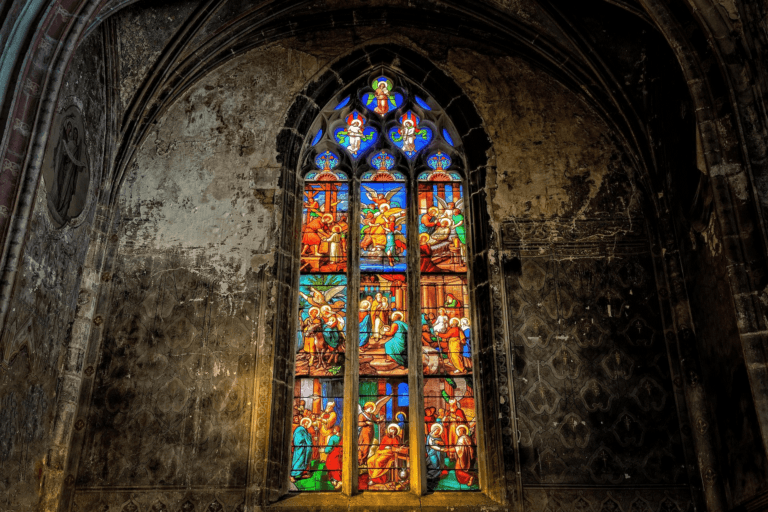

While some Romans succumbed to violence within the beleaguered city, others found refuge in churches, which Alaric had declared as sanctuaries. It displayed the Visigothic king’s complex character, respecting the sanctity of Christian sites amid the sacking. Yet the sparing of these spaces could not mitigate the broader destruction and the mass fatalities that accompanied the seizure of the Eternal City.

The aftermath of Alaric’s sack was a Rome that had been physically devastated and psychologically scarred. The city’s population was decimated, and the streets, once bustling with commerce and celebration, were littered with the remnants of a civilization under siege.

The exact quantity of treasure looted remains a matter of historical conjecture, but it was clear that Rome had been subjected to catastrophic material and human loss. As the dust settled, the sack of Rome stood as a grim testament to the end of an epoch, a once-impenetrable city brought to its knees by a leader who had once fought alongside the very Empire he had now helped to dismantle.

Alaric’s Final Journey and Enduring Legacy

The sack of Rome in 410 marked a pivotal moment in history, a blow that resonated through the Empire, exacerbating the Roman populace’s existing trauma from years of fear, hunger, and disease. Yet Alaric’s presence within Rome’s storied walls was fleeting. Merely three days post-sack, he directed his forces southward towards Campania with designs to cross to Sicily in search of supplies.

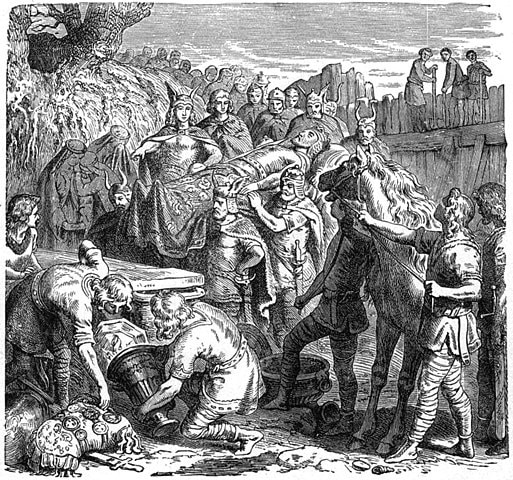

Fate, however, intervened when a tempest shattered his fleet. Stricken by illness on the return journey through Italy in the early months of 411, the Gothic King succumbed to fever at Consentia in Bruttium. His burial, steeped in the ceremonial grandeur of the Visigothic tradition, saw his body and treasures entombed beneath the Busento River, the grave’s location concealed forever by the murder of those who had wrought it.

The void left by Alaric’s death was swiftly filled by his brother-in-law, Ataulf, who continued the legacy of Visigothic leadership. Ataulf’s union with Galla Placidia, a marriage that melded Gothic prowess with Roman imperial lineage, was symbolic of the shifting power dynamics of the time. Under Ataulf’s guidance, the Goths consolidated their presence within the Empire, eventually settling in the Roman province of Aquitaine. Michael Kulikowski observes that Alaric’s leadership endowed his people with a communal identity that withstood the test of time, ultimately leading to establishing the Visigoths’ first sovereign kingdom within the Roman frontiers.

The repercussions of Alaric’s reign extended beyond his death and the foundation laid in Aquitaine. His actions catalyzed the emergence of Germanic barbarian groups across Western Europe, signaling the fragmentation of Roman authority and the dawn of a new era dominated by these ascendant powers. The Visigoths in Spain and Aquitaine, Vandals in Spain and later Africa, Burgundians along the Rhine, and Franks in the north were all part of this transformative movement that reshaped the continent.

Alaric’s legacy is multifaceted. He is remembered as the barbarian chieftain who dared to breach Rome’s inviolable sanctity, symbolizing the end of an age and presaging the tumultuous centuries to come. Yet, he is also regarded as a leader who sought to integrate his people into the Roman fold, not through assimilation but by recognizing their distinct identity within the Empire’s domain. His efforts laid the groundwork for the complex interplay of Roman and barbarian cultures that characterized the early medieval period.

In retrospect, Gothic incursions into Rome can be seen as both a terminus and a genesis—a conclusion to the unchallenged supremacy of Rome and the beginning of a period where the power of the Roman name would increasingly be shared with and eventually overshadowed by, the very barbarians it had once sought to subjugate.