Siege of Malta: The Battle for the Mediterranean

The 1565 Siege of Malta is one of the most celebrated battles in European history. That summer, the Mediterranean Sea was on fire. The Ottomans, at the peak of their power under Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, sought to utterly destroy the Knights of St. John and conquer the central sea. A few thousand defenders on a rocky island prepared to withstand one of the most significant invasion forces in history. The result was a four-month battle of fire and faith that would change the course of history.

It was a battle in every sense of the word. The stakes for the Ottomans were revenge and conquest: the last barrier to their control of the western Mediterranean and a gateway into Europe. The stakes for the Knights were existence itself, and they knew it. This was a fight not for land, but for faith and identity. Against overwhelming odds, the defenders turned Malta into a bulwark of resistance, transforming the siege of Malta into a battle not just for one island, but for the soul and future of the Mediterranean.

Background: The Mediterranean in Crisis

The Mediterranean Sea, by the mid-1500s, had become a grand frontier. To the east, Ottoman forces held sway from the Balkans to North Africa; their fleets ruled the eastern sea, their armies spread unceasingly over the southern reaches of Europe. From Constantinople, Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent built a maritime and military empire unequaled in both its strength and ambition. The Mediterranean might soon be an Ottoman lake: Tunis and Tripoli, Gdańsk and Buda, and other cities of southern Europe fell to the Crescent. Few harbors remained safe from Ottoman raids, and resistance in Europe was dwindling to defend the remaining ones.

At Constantinople, the Spaniards, the Pope, and the Venetians alike regarded the Ottoman advance with a mixture of dread and envy. The West was rent by the Reformation, and Christian Europe was no longer the tightly-knit system it had been before 1500; it was no longer a single political or even religious force with which Suleiman had to deal.

Spain was in an impossible position, with a large army and navy embroiled in a fruitless conflict in the Netherlands, as well as its forces in the New World; Emperor Charles V could not afford to further weaken his treasury with the declaration of another war against the Ottomans. The Venetians depended on the Mediterranean for trade, and dared not face a potential Ottoman blockade of the Adriatic. Europe’s defense against Ottoman expansion was left to the fractured, self-interested power players of the south, like the Knights of St. John.

The Knights Hospitaller, or Knights of St. John, was a crusading order established after the First Crusade to defend Christian pilgrims and territory in the Holy Land. The Knights, once expelled from Jerusalem, went on to fortify several outposts around the Mediterranean, most notably Rhodes. At Rhodes, the Knights built a mighty, enduring fortress to defend against Muslim encroachment. The Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, however, took Rhodes from the Knights in 1522 after a grueling blockade and desperate last stand by the Hospitallers.

For the next seven years, the Knights floated across Europe, offered haven by every Catholic power, until the emperor granted the small islands of Malta and Gozo as a base of operations in 1530. The Knights made a name for themselves in this period, raiding the eastern Mediterranean and North Africa for Christian slaves in an effort to rebuild their ranks and coffers.

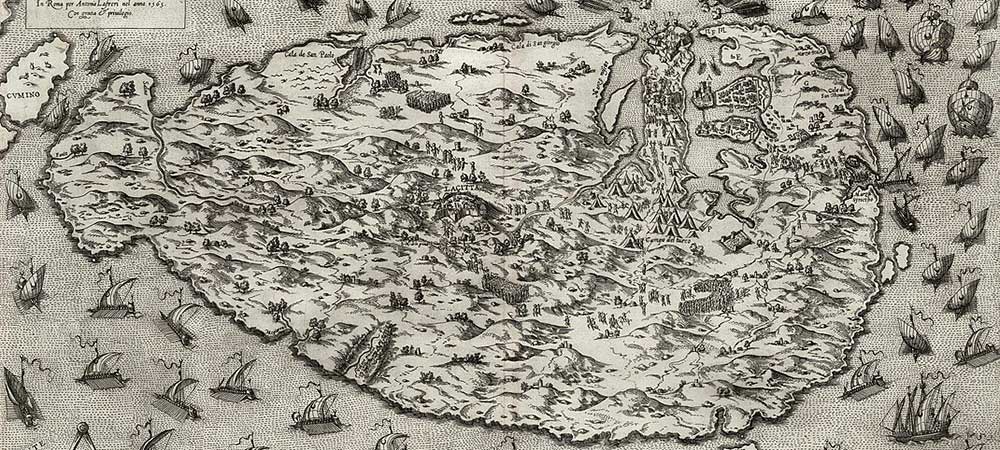

Malta was a small, stony island. Barely more than 100 square miles, it was not the most fertile or prosperous of the islands around the Mediterranean, but to the Knights, the strategic position of Malta was its most desirable feature. Between Sicily and North Africa, Malta commanded one of the busiest intersections in the entire Mediterranean. Whoever held Malta held the crossroads between the east and the west, between Europe’s busy trading ports and the spice and silk routes of the Levant.

The Knights Hospitaller moved quickly to establish themselves, bringing engineers to build the most extensive fortifications possible given their resources. Malta, under the Knights, had massive new walls; fortifications at Birgu and St. Angelo turned this small outcrop of rock into a bastion of the Christian world.

For the Ottomans, Malta was a dangerous nuisance, a jumping-off point for the Knights’ raids on the coast and their enslavement of Christians. Each foray from Malta was a provocation, each success by the Knights a blow to the pride of the Ottoman Empire. The Knights developed a tradition of attack on Ottoman shipping, privateering from Malta and inflicting damage and embarrassment on Suleiman’s imperial authority. After decades of relative peace, tension in the Mediterranean mounted. Suleiman, no stranger to showmanship and intimidation, decided to make an example of the Knights.

The Road to Siege

By the early 1560s, the Knights of St. John had transformed Malta from a rocky refuge into a formidable fortress. From its harbors, their swift galleys struck Ottoman shipping and coastal settlements across the Mediterranean. These raids liberated Christian captives and seized valuable spoils, but they also enraged the Ottoman Empire. The Knights’ daring attacks, though small in scale, were symbolic affronts to Ottoman dominance at sea. Their presence on Malta—strategically perched between Europe and North Africa—was an ongoing provocation that Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent could no longer ignore.

In 1564, the Knights captured several Ottoman vessels returning from North Africa, including one laden with valuable goods. Among the prisoners were relatives of key Ottoman officials. The insult was too great for Suleiman to tolerate. The sultan, now in his seventies and nearing the end of his reign, resolved to destroy the Order of St. John once and for all. To him, Malta was not merely an island—it was a dagger pointed at the heart of Ottoman sea power.

Suleiman ordered the assembly of one of the largest invasion forces the Mediterranean had ever seen. Nearly 200 warships, galleys, and transport vessels carried an estimated 40,000 men, including elite Janissaries, seasoned corsairs, and siege engineers. Command was divided between Mustafa Pasha, the veteran Ottoman general, and Piyale Pasha, the admiral of the Ottoman fleet. They were also accompanied by Turgut Reis (known as Dragut), the most feared corsair of the age, whose knowledge of Mediterranean warfare was unmatched.

Facing this vast force was a tiny garrison of roughly 600 Knights of St. John, backed by about 6,000 Maltese militia and European mercenaries. Their leader, Grand Master Jean Parisot de Valette, was seventy years old but unyielding in spirit. A veteran of decades of conflict against the Ottomans, Valette knew the enemy’s strength—and his own men’s resolve. “The Turks,” he declared, “are not accustomed to fighting against a united people who prefer death to the loss of their faith.”

As the Ottoman armada sailed westward from Constantinople in the spring of 1565, reports spread like wildfire through Europe. Yet few believed Malta could hold out for long. When the invasion fleet appeared on the horizon on May 18, the defenders prepared to meet a storm unlike any they had ever faced. The island, small and sunbaked, would soon become the stage for one of the most brutal sieges in history—a battle that would decide not only Malta’s fate, but the future of the Mediterranean world.

The Great Siege of Malta Begins (May 1565)

The Ottoman fleet arrived off Malta in May 1565, its sails blackening the sky as it anchored in Marsaxlokk Bay. The first target was Fort St. Elmo, a small but strategically important fort on the tip of the peninsula that guarded the entrance to the Grand Harbour. If the Turks captured it, they would have a clear path to the leading defensive positions at Birgu and Senglea. Grand Master Jean Parisot de Valette knew the fortress could not hold out for long, but ordered the Knights to defend it to the last man. About 150 knights and several hundred Maltese defenders manned the battered fortifications, determined to delay the enemy as long as possible.

On May 24, the Ottoman bombardment began. Hundreds of cannons roared day and night, battering the bastions to rubble. When the infantry assaults came, the defenders repelled them time and again, fighting with pikes and swords when they ran out of powder, hurling burning oil into the Turkish ranks. Their courage was something of a legend even among their enemies. Turkish soldiers reported that the defenders “fought like lions and would not surrender.” The guns of Fort St. Elmo continued to fire, and the Ottoman ships were forced to drop anchor far out to sea to avoid being sunk.

Suleiman’s generals, Mustafa Pasha and Piyale Pasha, expected the fortress to fall in days, but it took over a month to capture the shattered ruins. Each failed attack cost the Ottomans hundreds of men. Even as the walls had nearly all been breached, the defenders refused to surrender. Valette brought reinforcements by boat in the cover of darkness, ferrying men across the harbor despite the hail of enemy fire. The defenders of Fort St. Elmo had made a martyr of their fortress, a symbol of defiance that would inspire all of Christendom.

On June 23, 1565, after thirty days of siege, the Ottomans at last overran the shattered fort. Almost none of the original defenders were still alive. The wounded survivors were executed, their corpses nailed to crosses and floated across the harbor to mock the defenders of Fort St. Angelo. In retaliation, Valette had a group of captured Turks crucified, then had their heads fired back by cannon—grim proof that the siege of Malta had become an affair of extermination.

St. Elmo had served its purpose, however. The Knights had exacted a terrible price. The Ottomans had lost over 6,000 men, many of them elite Janissaries, and the famed corsair (Ottoman Naval Commander) Dragut was killed by shrapnel during the bombardment. What was supposed to have been a lightning victory had turned into a bloody quagmire. The Knights had bought time—time to prepare the defenses of Birgu and Senglea, time to send for aid from Sicily. The loss of Fort St. Elmo was not a defeat, but the first step in the long road toward victory.

The Turning Point

With Fort St. Elmo’s fall, the full force of the Ottoman assault was directed at Birgu and Senglea. Grand Master Jean Parisot de Valette remained calm and collected, becoming a symbol of resistance and hope for the defenders. He personally roamed the ramparts every morning in his worn armor, encouraging the men with speeches of faith and resilience. Valette inspired his men, reminding them that they were fighting for Malta and for all of Christendom. He strictly enforced discipline, punishing deserters but also publicly rewarding acts of bravery. His leadership bolstered morale, even as the walls trembled under the relentless cannonade.

July and August saw continued Ottoman bombardments from both land and sea. Fort St. Angelo, the Knights’ headquarters across the Grand Harbour, took thousands of shots. Casualties among the defenders mounted daily, but Valette would not be moved to cede ground. When an Ottoman bombardment breached a portion of Birgu’s defenses with a massive explosion, Valette personally led a counterattack with sword in hand. He drove the Janissaries away from the breach, shouting, “God has given them into our hands!” at the weary but inspired men. The Grand Master’s personal bravery on the front lines was a powerful morale booster that orders alone could not have achieved.

The superior numbers of the Ottoman army could not overcome the courage and determination of Valette and his defenders. The initial momentum and confidence they had at the beginning of the siege had waned after weeks of fighting. Ottoman soldiers now faced disease, food shortages, and the unrelenting Mediterranean sun. Disease spread through their camp as their stores dwindled, and the soldiers began to suffer greatly under the island’s climate.

Continuous Ottoman attacks on the defenses of Birgu and Senglea were repulsed with heavy casualties. A once-feared army that had come to the island to utterly crush the Knights of St. John was now hemorrhaging men, with no end to the siege in sight. Mustafa Pasha grew increasingly frustrated as morale in his camp fell. Word spread among the troops that the Grand Master would never surrender, and murmurings of retreat grew in the ranks.

In early September, hope arrived in the form of relief from Sicily. Viceroy Don García de Toledo had despatched a relief force of about 8,000 Spanish and Italian troops under the overall command of Don Juan de Logn. Landing on the island, they were a small force in comparison to the Ottoman army, but one that electrified the defenders. Valette ordered an immediate counteroffensive in coordination with the new arrivals. The Knights and the newly-landed troops aimed to strike the now-weakened Ottoman lines while the Maltese militia, led by the Grand Master himself, attacked exposed Turkish positions.

The final days of the siege were a brutal and bloody melee. The battered and exhausted Ottoman forces could not hold their ground. On September 11, the defenders surged forward, pushing the Ottomans back towards the sea. By the time the Ottoman withdrawal began, what was left of the once-great invasion force was broken. Thousands of dead Ottomans littered the field as their ships burned in the harbor. The survivors boarded what was left of their fleet and sailed away, leaving Malta in ruins—but free. The heroism of Valette and his men had changed the course of the siege and, with it, the course of history in the Mediterranean.

Aftermath and Consequences

The smoke that had covered the island of Malta during the autumn of 1565 gave way to reveal a landscape changed beyond recognition. Of the approximately 40,000 men who had embarked under Mustafa Pasha and Piyale Pasha, as many as 25,000 were dead or unaccounted for. Thousands more were stricken with disease or nursing wounds. The proud Ottoman fleet limped back to Constantinople in humiliation, its aura of invincibility battered. Suleiman the Magnificent, livid over the defeat, reportedly declared he would avenge it, but never again tried to mount a full-scale invasion of the western Mediterranean before his death the following year.

Malta was a wasteland, and the population had been decimated by famine, bombardment, and disease. In the midst of the devastation, however, the island still stood, defiant. The survivors, among them the Maltese militia and the Knights of St. John, were hailed as heroes throughout Europe, as champions of the faith. Pope Pius IV praised them as “a bastion of Christendom,” and the Catholic world took the victory as a sign of divine intervention. Jean Parisot de Valette’s leadership in the siege elevated him to the status of legend. His name would become synonymous with courage and endurance.

The repercussions of the victory were felt far beyond Malta’s shores. For the first time in more than a century, the Ottoman expansion into Europe had been reversed. The battle shattered the prevailing sense of a juggernaut of Muslim conquest that had haunted Europe since the fall of Constantinople, and which would take generations to dissipate. In the years following Malta, Catholic powers in the Mediterranean—Spain, Venice, the Papacy—found ways to cooperate in confronting the Ottoman threat. Malta’s stand rekindled the confidence of many Europeans that the tide could be turned in the Mediterranean.

The psychological and strategic impact of the siege was immense. The defeat undermined Ottoman morale and contributed to a decline in their naval dominance in the central Mediterranean. The successful defense provided a model of unity and resolve that would echo in later alliances, most notably the Holy League. That coalition of Christian powers would go on to secure a decisive victory at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, a clash at sea that would in many ways be the natural continuation of the spirit born at Malta.

Centuries after the battle, the 1565 Siege of Malta would continue to be celebrated as a symbol of faith under fire and the defense of Europe’s frontiers. The fortifications rebuilt in its aftermath, including the city of Valletta, founded in 1566, would become living memorials to the sacrifice of its defenders. Malta’s survival had not only stopped the Ottoman advance—it had changed the course of Mediterranean history, and proved that even a small island, united in purpose, could withstand the might of an empire.

The Legacy of the Siege

In the aftermath of the Great Siege of Malta, Grand Master Jean Parisot de Valette emerged as one of Europe’s most celebrated figures. His leadership, courage, and unwavering faith during the ordeal immortalized him in history. To honor his legacy, the Knights of St. John founded a new fortified capital on the island in 1566—Valletta—bearing his name. Built atop the ruins left by war, the city became both a monument to survival and a symbol of Malta’s newfound strength. Its walls, bastions, and harbors embodied the spirit of endurance that had carried the island through its darkest days.

The Knights of St. John, once a scattered order driven from their home in Rhodes, became heroes of Christendom. Their defense of Malta transformed them from exiles into defenders of Europe. Monarchs and popes across the continent hailed them as warriors of faith and valor. Donations and recruits flooded into the Order, revitalizing its ranks and influence. For nearly two centuries after the siege, the Knights maintained Malta as a formidable bastion of Christianity and a strategic naval stronghold in the heart of the Mediterranean.

The battle itself soon entered legend, taking on a near-mythic quality as a “clash of civilizations.” Chroniclers, poets, and artists cast it as a struggle between the Christian West and the Islamic East, a defining confrontation for the soul of Europe. In reality, the siege was as much about power and control of trade routes as it was about faith. Yet, over time, the narrative of religious resistance became central to its memory. The story of Malta’s defense resonated across generations, shaping Western perceptions of heroism and destiny in the age of empire and crusade.

Strategically, the victory at Malta ensured that the island would remain one of the most vital naval and military outposts in the Mediterranean. Its harbors became staging grounds for European fleets and a barrier against Ottoman expansion into the western seas. The siege confirmed Malta’s role as the “gatekeeper of the Mediterranean,” a position it would hold well into the modern era. Even as empires rose and fell, Malta’s significance as a fortress island endured.

Today, the legacy of the 1565 Siege of Malta lives on not only in monuments and history books but in the identity of the island itself. Valletta stands as a living reminder of resilience, courage, and faith against overwhelming odds. The Knights’ victory echoed far beyond their time, proving that determination and unity could alter the course of history—and that even the smallest outpost could hold the fate of continents in its hands.