The Second Ottoman Siege of Vienna (1683) and The Battle That Saved Europe

The Second Ottoman Siege of Vienna in 1683 was pivotal in European history. It is often hailed as the battle that saved Europe from Ottoman domination. This dramatic confrontation unfolded as the culmination of a longstanding conflict between the Holy Roman Empire and the expansive ambitions of the Ottoman Empire.

The Prelude to the Second Ottoman Siege of Vienna

The lead-up to the Second Ottoman Siege of Vienna was marked by strategic maneuvers and political machinations that echoed throughout Europe that were very similar to those before the first besiegement of the city. The Ottoman Empire, seeking to capitalize on the longstanding chaos in Hungary, intensified its push towards Central European dominion. The siege, precipitated by the Ottomans’ desire to extend their influence into the heart of the Holy Roman Empire, began in earnest with Sultan Mehmed IV’s decision to leverage the military assistance they had provided to Hungarian and non-Catholic factions. This alliance with rebel forces under Imre Thököly, crowned King of Upper Hungary, played a crucial role in setting the stage for the 1683 campaign against Vienna.

Vienna, aware of the impending threat, braced for conflict. In the years preceding the siege, the city had experienced significant distress due to the plague, further complicating its defensive preparations. The political landscape of the time was fraught with tension as Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I’s efforts to suppress Protestantism in Hungary stirred dissent and rebellion, providing the Ottomans with a pretext to intervene militarily. The siege was not merely a sudden onslaught but the culmination of a calculated build-up of Ottoman military presence in the region, underscored by the ambitious aim of capturing Vienna and reinforcing the Ottoman foothold in Europe.

As 1683 dawned, the Ottoman war machine, under the command of Grand Vizier Kara Mustafa Pasha, commenced its slow and menacing march towards Vienna. The Empire’s forces, swollen by allies and mercenaries, moved with deliberate intent, signaling their resolve to capture the strategic city. Vienna, for its part, fortified its defenses, bolstered by alliances with neighboring states and the promise of support from powers such as Poland, Venice, and the Papacy. The stakes were high, and as the forces encamped and began the Second Ottoman Siege of Vienna, the city’s fate hung precariously in the balance, setting the scene for one of the most significant sieges in European history.

Initial Assaults of the Second Ottoman Siege of Vienna

On July 14, 1683, the formidable Ottoman army, under the leadership of Grand Vizier Kara Mustafa, commenced the Second Ottoman Siege of Vienna. With a clear intention to capture the city, Kara Mustafa sent a formal demand for surrender, staunchly refused by Ernst Rüdiger Graf von Starhemberg, who commanded Vienna’s defense. Starhemberg, bolstered by approximately 15,000 troops and 8,700 volunteers, fortified the city, inspired in part by the horrific fate that befell Perchtoldsdorf, where citizens were massacred despite their surrender. This grim precedent solidified Vienna’s resolve to resist the siege at all costs.

Siege operations began earnestly on July 17. The defenders had preemptively cleared the area around the city walls, creating a killing field that would expose advancing Ottomans to deadly fire. In a tactical response, Kara Mustafa ordered the digging of extensive trenches towards the city walls to shield his forces. The Ottomans, equipped with 130 field guns and 19 medium-caliber cannons, were numerically outgunned by the city’s 370 cannons, setting the stage for a grueling conflict.

Underneath the city, Ottoman sappers worked tirelessly to undermine the walls by tunneling and filling them with explosives. The city’s ancient fortifications, largely decayed, posed an unexpected challenge to the attackers. In a defensive countermeasure, Viennese forces hammered massive tree trunks into the ground, significantly fortifying the barriers and consequently prolonging the siege by weeks. This fortification effort was critical, as it bought precious time for a relief force to gather and approach, a factor that would prove decisive later in the siege.

Kara Mustafa’s strategy reflected a cautious approach. Opting to preserve the city’s wealth, he avoided launching a full-scale assault that would trigger widespread looting, a common reward for conquering troops. This decision, aimed at capturing Vienna intact, inadvertently extended the siege, providing the beleaguered city with a crucial window to strengthen its defenses and prepare for the arduous battles that lay ahead.

The Siege Deepens & Forces Gather to Relieve the Second Ottoman Siege of Vienna: A Race Against Time

As the Second Ottoman Siege of Vienna intensified, the city’s defenders faced dire circumstances. By August, the Ottoman forces had effectively severed almost all supply routes, leaving Vienna isolated and desperate for resources. The situation grew so critical that the city’s commander, Ernst Rüdiger Graf von Starhemberg, issued orders to execute any soldier found sleeping while on watch, reflecting the severe strain on the defenders.

However, a glimmer of hope emerged when Imperial forces under Charles V, Duke of Lorraine, successfully defeated Imre Thököly’s troops at Bisamberg, just a few kilometers northwest of Vienna, suggesting that help was finally coming.

In early September, a pivotal shift occurred when King John III Sobieski of Poland crossed the Danube at Tulln, about 30 kilometers from Vienna, joining forces with the Imperial army along with additional contingents from Saxony, Bavaria, Baden, and other Holy Roman Empire states. Despite France’s Louis XIV choosing not to assist, fearing strengthening his Habsburg rival, the combined forces under Sobieski’s command prepared for a crucial confrontation.

The alliance was significantly bolstered by the addition of Polish hussars, renowned for their effectiveness in battle against the Ottomans. Sobieski, celebrated for his military prowess and previous victories such as the Battle of Khotyn, took command of an allied force between 70,000 and 80,000, ready to face the Ottoman army outside Vienna’s walls.

By this stage in September, the Ottoman sappers had made alarming progress, having demolished significant sections of Vienna’s fortifications and creating breaches that threatened the very survival of the city. In a desperate bid to thwart the Ottoman efforts, Viennese defenders began their tunneling operations to intercept and neutralize the Ottoman mines. The situation reached a critical point on September 8, when the Ottomans occupied key defensive positions near the city walls, prompting the Viennese to prepare for close combat within the city’s confines.

The tension between the imminent relief by the Allied forces and the increasingly successful Ottoman sapping operations marked a race against time, setting the stage for a decisive battle that would determine the fate of Vienna and possibly alter the course of European history.

Prelude to the Climactic Battle at Vienna

As the Second Ottoman Siege of Vienna intensified, the city braced for an imminent attack while a relief army quickly assembled to lift the siege. The multinational force, comprising primarily Polish and Imperial troops, had to swiftly forge a unified command under King John III Sobieski of Poland, renowned for his cavalry tactics with the formidable Polish Hussars. This alliance, formed in mere days, demonstrated remarkable logistic and diplomatic efficiency.

Funding for this massive undertaking was secured through various means, including substantial financial support from the Pope, wealthy bankers, and nobleman contributions. The Holy League agreed that while Polish troops would be financed by their government on Polish soil, the Holy Roman Emperor would assume financial responsibility once they entered Imperial territory. Moreover, an agreement was struck granting Sobieski first rights to plunder in the event of victory, underscoring the high stakes and rewards involved.

Conversely, Kara Mustafa’s forces showed signs of fragmentation and diminishing morale. The unreliable alliances within the Ottoman ranks complicated the defense strategy. The Crimean Khanate, led by the Khan of Crimea, displayed a conspicuous lack of aggression, notably refraining from engaging the relief force as it crossed the Danube and navigated through the Vienna Woods again. This hesitation played into the hands of the besieged, giving them crucial breathing space. Additionally, the involvement of Ottoman vassal states like Wallachia and Moldavia was tepid at best, with notable figures such as Șerban Cantacuzino shifting allegiances after the battle began, further undermining the Ottoman campaign.

The dramatic convergence of these forces was heralded by bonfires lit by the confederated troops atop the Kahlenberg, a signal reciprocated by the beleaguered city of Vienna. In a daring maneuver, Jerzy Franciszek Kulczycki, a Polish nobleman adept in Turkish, infiltrated the Ottoman camp.

His successful espionage was critical, providing the relief army with vital intelligence on the Ottomans’ positions and readiness. This strategic coordination set the stage for one of the most significant battles in European history as the allied forces prepared to make their decisive move against a besieging army plagued by internal discord and strategic missteps.

The Climactic Battle of Vienna

On the morning of September 12, 1683, the Second Ottoman Siege of Vienna reached its zenith with a grand assault by the Ottoman forces under Kara Mustafa Pasha. The engagement began before dawn, catching some of the Holy League forces while still arranging their positions. Despite the surprise and the formidable size of the Ottoman army, estimated at over 150,000, the defenders of Vienna, numbering around 20,000, bolstered by the recently arrived reinforcements numbering approximately 65,000, held their ground.

The Ottomans launched their attack around 4:00 a.m., focusing initially on the northern sectors held by German and imperial forces. Despite being outnumbered, these troops managed to repulse the Ottomans, capturing strategic locations such as Nussdorf and Heiligenstadt, causing severe casualties to the Ottoman ranks.

As the day progressed, the battle’s intensity did not wane. By midday, the imperial forces had gained significant ground, thwarting multiple Ottoman counterattacks. Meanwhile, the Polish forces under King John III Sobieski prepared for a critical maneuver. Known for his military acumen, Sobieski had aligned his famed cavalry, including the formidable Winged Hussars, for a decisive charge. The tactical positioning of the Allied forces gradually encircled the Ottoman troops, squeezing them against their own lines.

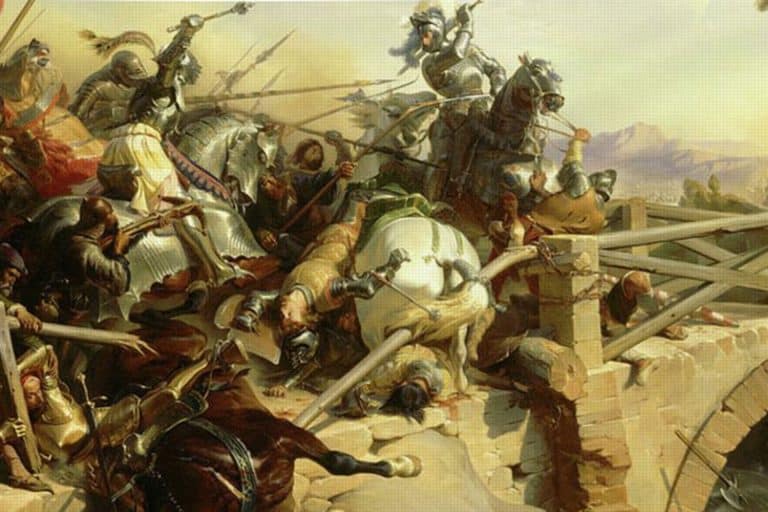

The turning point came in the late afternoon when the Polish cavalry launched one of the largest cavalry charges in history. Approximately 18,000 horsemen, including 3,000 heavy Polish Lancers or Winged Hussars, led by Sobieski himself, thundered across the Kahlenberg hills towards the beleaguered Ottoman camps. The charge was massive but meticulously timed, coinciding with a coordinated push by the German and Austrian forces from the north. The combined assault overwhelmed the Ottoman defenses, which were already buckling under the pressure of the sustained attacks and the earlier failures in their sapping efforts.

By the evening, the battle had decisively favored the Holy League. The Ottoman forces, demoralized and exhausted, began a disorganized retreat. The loss of life was substantial on both sides, with the Ottomans suffering approximately 15,000 casualties, including the dead and wounded, while the defenders incurred around 4,000 casualties.

The victory at Vienna lifted the siege and marked a turning point in the Ottoman Empire’s expansion into Europe, heralding a period of gradual retreat and decline in their territorial ambitions in the continent. The Holy League’s triumph was celebrated across Europe, with Sobieski hailed as the savior of Christendom, embodying the resilience and unity that had prevailed against a formidable foe.

The Enduring Impact of the Second Ottoman Siege of Vienna

The Second Ottoman Siege of Vienna in 1683 marked a critical turning point in European history, culminating in an Ottoman defeat that would have far-reaching consequences. Historical records, including those by Ottoman historian Silahdar Findiklili Mehmed Agha, depict this battle as one of the most significant losses for the Ottoman Empire since its inception in 1299. The siege and the subsequent battle led to substantial Ottoman casualties, with estimates suggesting around 15,000 to 20,000 soldiers lost, in stark contrast to the significantly lower casualties of the defending coalition led by King John III Sobieski of Poland.

In the immediate aftermath of the battle, Vienna rapidly moved to repair its defenses, forever wary of another potential Ottoman threat—a threat which, following this defeat, never materialized again. The victory allowed the Viennese and their allies to capture a substantial amount of loot from the defeated Ottoman army, bolstering the city’s resources and morale. Sobieski vividly described the vast treasures seized in his correspondence, underlining the scale of the Ottoman loss. Yet, despite this triumph, tensions among the victors, particularly over the division of spoils and subsequent military support, marred the alliance’s unity.

The failure at Vienna was disastrous for Kara Mustafa Pasha, the Ottoman grand vizier who led the siege. His defeat was perceived so negatively that it led to his execution later that year, marking a significant shift in Ottoman military fortunes and prestige. Internally, the Empire faced criticism and a reassessment of its military strategies, while externally, it sparked a change in European dynamics, strengthening the resolve of the Habsburgs and their allies.

Following the siege, the broader implications for Europe were significant. The victory at Vienna and the successful repulsion of the Ottoman forces set the stage for the Habsburgs’ expansion into Hungary and other territories previously under Ottoman control. These conquests during subsequent years solidified Habsburg influence in Central Europe and diminished Ottoman influence in the region, culminating in the Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699, which ended the conflict and redrew the map of Europe.

This battle saved Vienna and significantly halted Ottoman expansion into Europe, marking a decline in their imperial ambitions and a shift in European power dynamics. The successful defense of Vienna preserved its status as a significant cultural and political center of Europe, influencing military strategies and alliances for years to come. The legacy the Second Ottoman Siege of Vienna and the subsequent Battle continue to be studied and remembered as a pivotal moment in European history, where a coalition of forces under the banner of the Holy League managed to thwart one of the most significant threats to Christian Europe at the time.