The Diadochi: How Alexander’s Generals Built New Empires from His Ashes

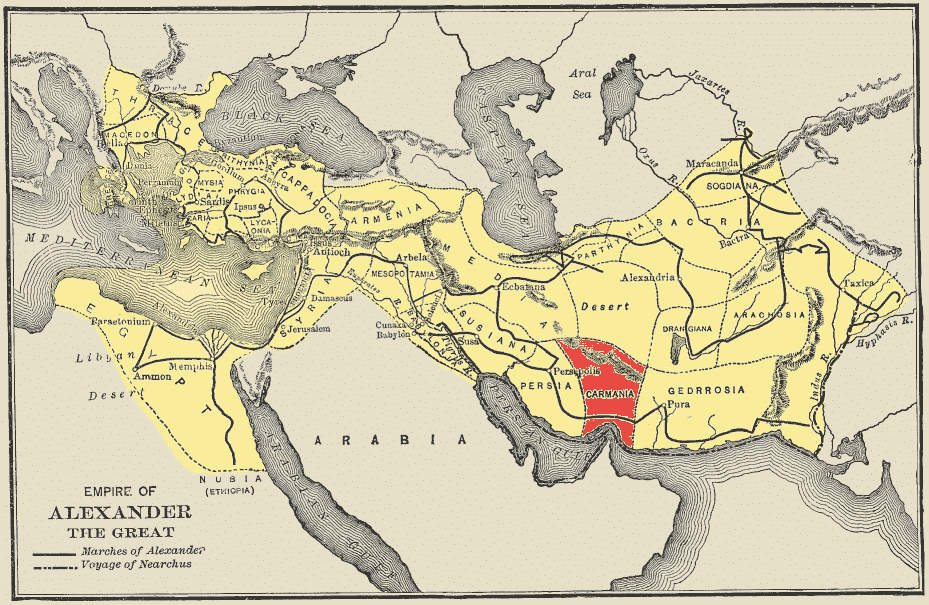

Alexander the Great died unexpectedly in Babylon in 323 BCE with no clear successor. His empire, which had expanded from Greece to India, and his only legitimate son were yet unborn; his half-brother, the only possible candidate, was mentally unfit. It was into this succession crisis that his most trusted generals, later known as the Diadochi, meaning “successors” in Greek, emerged as the new power brokers. Almost half a century of bloodshed, rapidly forged and broken alliances, and political maneuvering ensued as the Diadochi fought over their share of the pie.

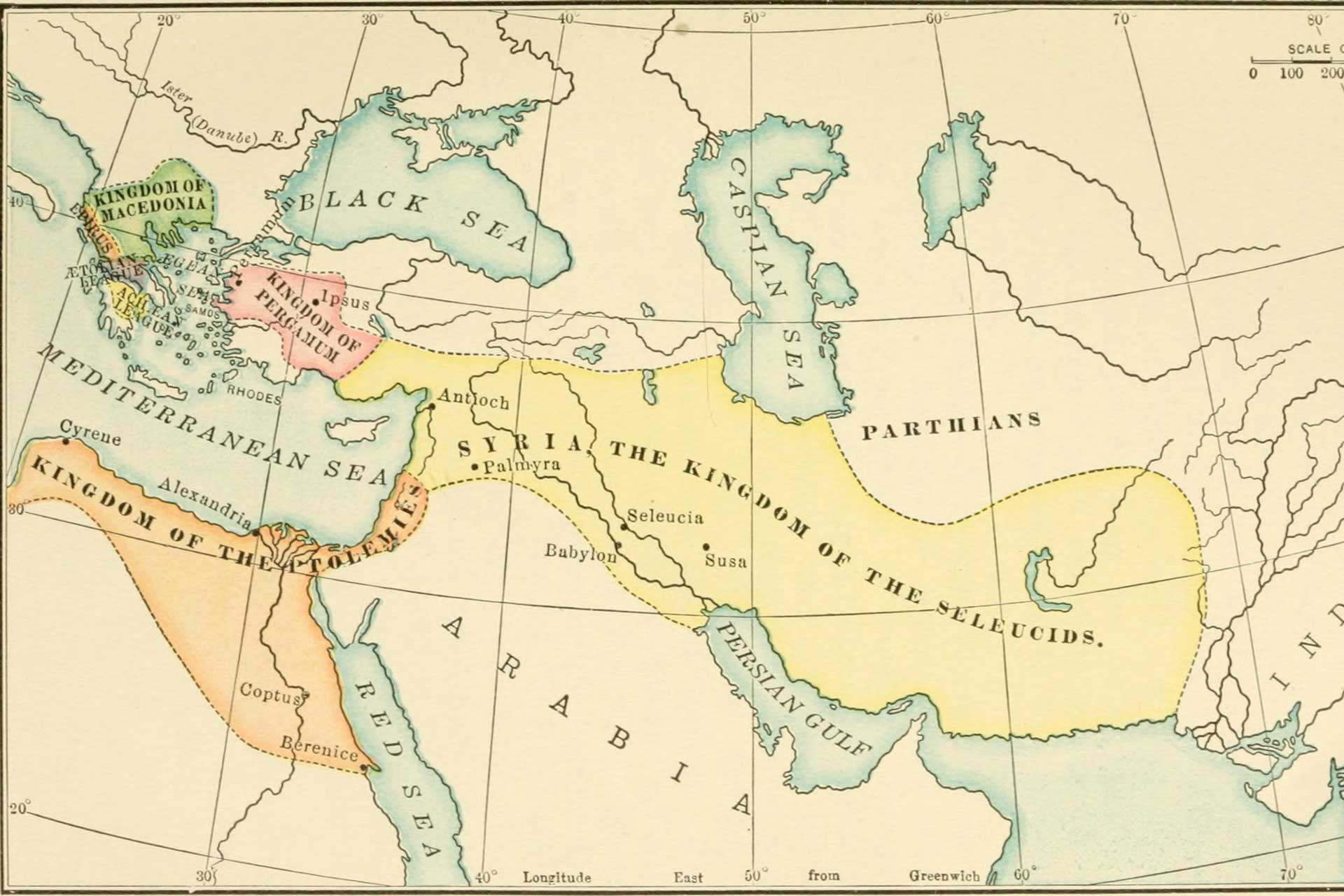

In the end, though Alexander’s empire had long since splintered, the Diadochi established large successor kingdoms of their own. In addition to the Seleucid, Ptolemaic, and Antigonid empires, their other kingdoms also spread and cemented Alexander’s conquests, and extended his legacy far beyond the borders of his empire. The cultural and political changes they wrought from Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean effectively marked the beginning of the Hellenistic Age.

The Death of Alexander and the Struggle for Power

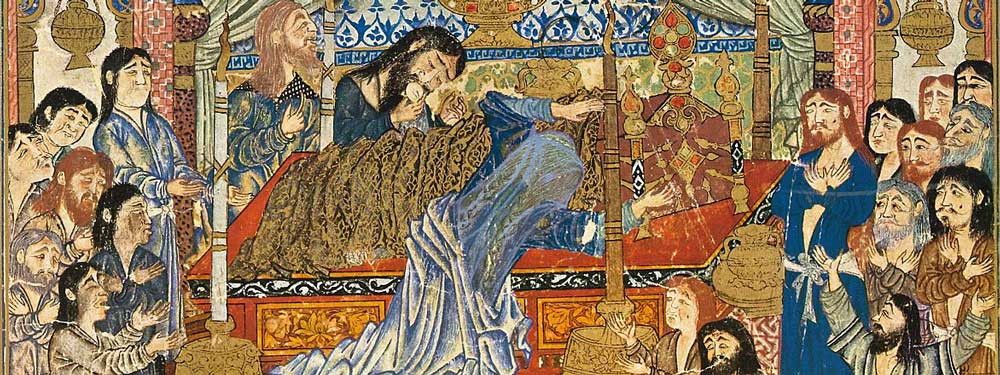

The premature death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE sent ripples of shock through the ancient world. At just 32 years old, after only a few days of illness, possibly due to fever, poisoning, or natural causes (sources differ), he died in Babylon, and the unimaginable happened. The consequences of Alexander’s death were not just the size of his empire but the uncertainty and confusion around his succession. To his deathbed question by his companions about who was to succeed him as king, Plutarch’s account has him quipping in reply, “To the strongest.”

The issue of an heir to Alexander was one that the Macedonian king had left undecided. His wife, Roxana, was pregnant with a son, Alexander IV, but he was still years from reaching maturity, and his legitimacy as an heir was open to question. His half-brother Philip III Arrhidaeus was a possible successor, but his severe mental disability meant he was considered an unfit ruler. In the absence of any other legitimate and able-bodied claimant, the succession of power fell to his senior generals and companions, many of whom had once commanded his armies and administered satrapies.

To give the appearance of continuity and solidarity, the Partition of Babylon was quickly assembled after Alexander’s death. The empire was divided into regional spheres of influence. At the same time, the office of kingship was placed in the hands of the hapless Philip III, and from the following year, the infant Alexander IV. A regency was established in the person of Perdiccas. Intent on holding the empire together, at least initially, he planned to place Alexander’s body where it would serve as a focus of loyalty for the kingdom.

The generals, known as the Diadochi, also had to reach some accord over the disposal of the empire, and it was at this point that each was assigned his share. Ptolemy, son of Lagus, took Egypt, Antigonus was given Asia Minor, while Seleucus was rewarded with a position in Babylon. Other generals, such as Lysimachus and Cassander, would also emerge into the upper echelons of power. However, the arrangements reached at Babylon were to be more of a prelude to division than a division itself.

The breakdown of the arrangements made in Babylon was swift. Mutual distrust and anxiety grew between the successors. Each of them was accustomed to a large degree of autonomy in their regions, and the preservation of power became more important than unity or obedience to imperial orders. Loyalty was bound not so much to an idea but to their memory of Alexander, as well as personal ambition, greed, and fear. The generals all used the name of the young Alexander IV to claim legitimacy, even as they acted more in their own interests. This included strengthening and expanding their armies, increasing taxes, and other measures.

Empires were kept together through alliances between the generals, and rivalries festered in the background. Assassinations were plotted against one another, whether to gain more territory, power, or influence over the regency itself. Perdiccas, the first regent after Alexander, would be among the first to be caught up in this vicious world and be killed after only three years. It is not too much to say that the empire was coming apart behind the pretense of continuity and empire. Still, the heirs of Alexander were not yet ready to formally divide the empire among themselves.

The Wars of the Diadochi

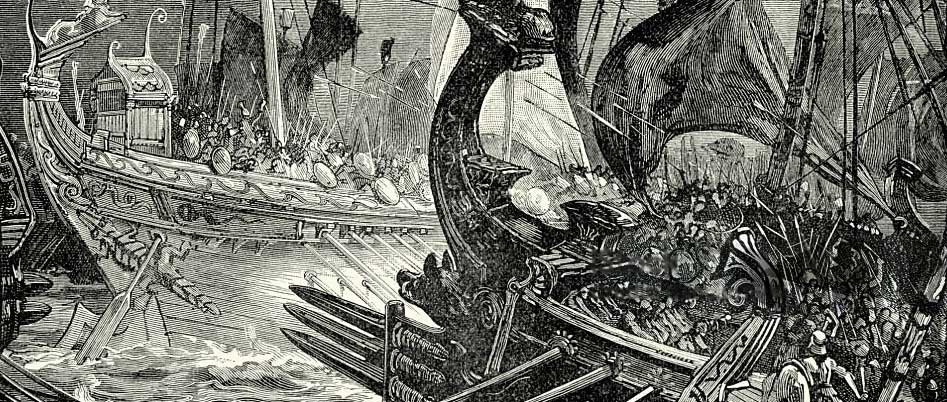

In the wake of Alexander’s death, the uneasy peace among his former generals disintegrated rapidly into a bloody and protracted struggle for power and territory. These conflicts, collectively known as the Wars of the Diadochi, spanned roughly five decades, characterized by frequent shifts in alliances and rapid territorial exchanges.

The First War of the Diadochi (322–320 BCE) broke out when Perdiccas, the regent for the new kings, sought to assert his authority over the other generals. Ptolemy’s refusal to submit to Perdiccas in Egypt precipitated a conflict that culminated in a failed invasion of Egypt by Perdiccas and ultimately led to his assassination. In the aftermath, Ptolemy solidified his control over Egypt, while Seleucus fled Babylon only to return later with support from Antigonus the One-Eyed. Antigonus emerged as a preeminent power in Asia and Syria, even going so far as to assume the title of king and to dethrone other Diadochi, alarming the others and leading to a coalition against him.

A series of crucial battles and political maneuvers defined this era. The Battle of Ipsus in 301 BCE, where Antigonus was defeated and killed by a coalition led by Seleucus, Lysimachus, and others, marked a turning point that effectively ended any pretense of reuniting Alexander’s empire. With Antigonus out of the picture, it became clear that the empire could not be held together. The remaining Diadochi, now more focused on consolidating their gains than on expansion, entered a period of relative stability in their regions.

The Wars of the Diadochi were marked by intrigue, betrayals, and shifting alliances. Treaties were made and broken, heirs were displaced or assassinated, and the legitimacy of succession was a recurring issue. The supposed co-kings, Philip III and Alexander IV, were both ultimately murdered, marking the end of the Argead dynasty and, ostensibly, of Alexander’s empire. Control of key regions and cities, such as Babylon and various Greek city-states, changed hands multiple times during these wars.

By 281 BCE, with the death of Seleucus I at the hands of Lysimachus, the long era of the Diadochi wars came to an end. Alexander’s once-mighty empire was now divided among his former generals, forming the Hellenistic kingdoms: the Seleucid Empire in the East, the Ptolemaic Kingdom in Egypt, and Macedon under the Antigonids. These states were Greek in culture and influence, but they ruled independently; their borders and policies were shaped by the ambitions and legacies of Alexander’s former commanders.

Despite the considerable bloodshed and destruction, the Wars of the Diadochi set the stage for centuries of Hellenistic rule, during which the Greek language, art, and ideas continued to spread and take root across Asia and North Africa within these successor states. For better or for worse, the Diadochi ensured that Alexander’s legacy would endure, even if his empire did not.

The Major Successor Kingdoms

The Seleucid Empire (Seleucus I Nicator)

Seleucus I Nicator, another of Alexander’s generals, was born in either Asia Minor or Babylon to a family of mixed Greek and non-Greek heritage. When Alexander died, Seleucus, the satrap of Babylon, fought and conquered to establish one of the largest and most powerful Hellenistic states, the Seleucid Empire.

This vast territory, which included Mesopotamia, Persia, Syria, and much of Central Asia, at its height reached from the Aegean Sea to the borders of India. Seleucus was renowned for his expertise in both diplomacy and military strategy, successfully maintaining his control over the diverse regions of his empire. His reputation as one of Alexander’s most successful successors was cemented when he emerged victorious at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BCE.

Seleucus faced many challenges throughout his reign. The vast and culturally diverse territories of the Seleucid Empire were difficult to manage and were often the sites of revolts, particularly in the eastern satrapies where local satraps often tried to assert their independence from Macedonian rule. The Seleucid Empire also faced threats from powerful neighbors, such as the Mauryan Empire in India. Seleucus had initially expanded into the Mauryan territories but was forced to cede them to Chandragupta Maurya in exchange for 500 war elephants, a diplomatic and military decision that would prove to be advantageous in his future conflicts.

In an effort to legitimize and consolidate his rule, Seleucus founded a new capital city, Seleucia on the Tigris, around 305 BCE, which would later become one of the most significant cities in the ancient world, and a later capital Antioch in Syria after his father. These cities served as important administrative and cultural centers, symbolizing the fusion of Greek and Eastern cultures that was a hallmark of the Seleucid dynasty.

The Seleucid kings, true to their Hellenistic roots, encouraged the spread of Greek culture throughout their empire. They founded new Greek-style cities and settled Greek colonists in these and other existing cities throughout their territories, leading to the spread of the Greek language, religion, and art. At the same time, they also maintained many of the Persian court rituals and administrative practices, creating a unique hybrid culture and government. This cultural syncretism is evident in the Seleucid coinage, which frequently depicted both Greek and Persian deities, as well as in their temple architecture and urban planning.

The Seleucid Empire, however, gradually declined after the death of Seleucus. Internal strife, rebellious satraps, and wars with other Hellenistic states, such as the Ptolemies of Egypt, as well as later threats from the rising Parthians, gradually eroded the Seleucids’ power. By the 2nd century BCE, the empire had lost much of its eastern territory, and Roman intervention further reduced its power. The Seleucid dynasty came to an end in 63 BCE when the Roman general Pompey conquered Syria, effectively bringing the Seleucid Empire to a close.

Despite their eventual downfall, the Seleucids left a lasting legacy. Their empire served as a bridge between East and West, and their rule helped to spread Hellenistic culture throughout Asia. They played a crucial role in preserving and transmitting Greek knowledge and culture, while also integrating aspects of the cultures they ruled over, making them one of the key builders of the world after Alexander.

The Ptolemaic Kingdom (Ptolemy I Soter)

Ptolemy I Soter was a prominent general under Alexander the Great and became ruler of Egypt after Alexander’s death in 323 BCE. Initially serving as the satrap of Egypt, Ptolemy swiftly took steps to assert his independence, establishing a dynamic and enduring Hellenistic kingdom. His territories included not only Egypt but also portions of the eastern Mediterranean, such as Cyprus and parts of the Levant. Ptolemy’s reign marked the start of the Ptolemaic dynasty, which would rule Egypt for nearly three centuries.

Ptolemy’s most audacious move was the appropriation of Alexander’s body, which he transported to Memphis. This symbolic act tied his reign to Alexander’s legacy and influence. The body was later moved to Alexandria, which Ptolemy and his successors developed as the new capital. This was a clear sign of the king’s ambition and was intended to project his legitimacy. The city of Alexandria quickly evolved into a vibrant hub of trade, culture, and Hellenistic learning.

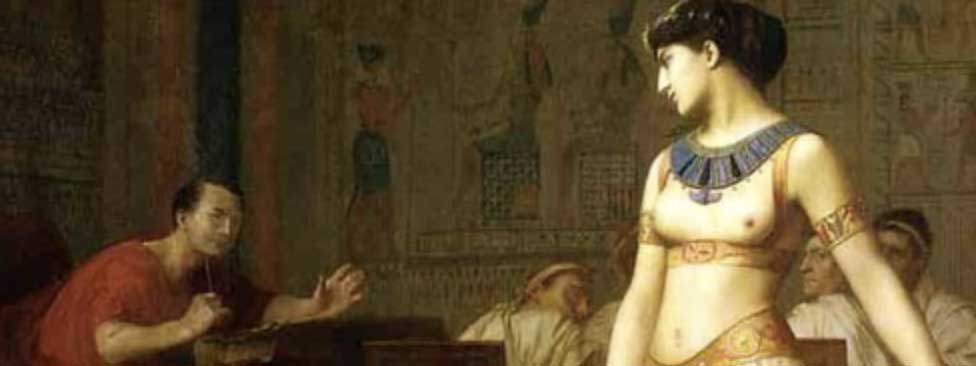

The Ptolemies were successful in blending Greek and Egyptian cultures. They styled themselves as Hellenistic kings and pharaohs, embracing Egyptian religious iconography and ritual. This syncretic approach helped ensure stability while also appealing to the kingdom’s Greek and Egyptian subjects. The Ptolemies built extensively in the Egyptian temple style and sponsored religious festivals, further legitimizing their rule.

The enduring legacy of the Ptolemaic Kingdom is its contribution to scholarship and the arts. The Great Library of Alexandria, possibly established by Ptolemy I or his son Ptolemy II, aimed to collect all the world’s texts and became a hub of intellectual activity. The associated institution, the Mouseion, patronized poets, scientists, and philosophers, making significant contributions to various fields. This intellectual patronage ensured that Alexandria was considered the cultural and intellectual center of the Hellenistic world.

The Ptolemaic dynasty was long, with many successors. However, it is Cleopatra VII that many will recall as Egypt’s most renowned queen. Her multilingual abilities and diplomatic skills exemplified the dynasty’s cultural fusion. Cleopatra formed alliances with Julius Caesar and Mark Antony, but following their defeat by Octavian (later known as Augustus), Egypt became a province of the Roman Empire. In 30 BCE, the Ptolemaic Kingdom fell, marking the end of the Hellenistic period.

The Ptolemaic Kingdom is one of the more notable of Alexander’s legacies. It was the longest-lasting of the Diadochi kingdoms and was particularly successful in merging the cultures of Greece and Egypt. Through shrewd political maneuvering, cultural patronage, and symbolic acts such as the appropriation of Alexander’s body, Ptolemy I and his descendants transformed Egypt into a lasting and influential Hellenistic state. This legacy continues to fascinate scholars and the public today.

The Antigonid Kingdom (Antigonus I Monophthalmus and Demetrius)

The Antigonid dynasty was one of the main successor states to Alexander the Great’s empire. The Antigonids were descended from Antigonus I Monophthalmus, one of the Diadochi or successors to Alexander. The name Antigonus means “equal to the grandfather” in Greek and he was given the epithet Monophthalmus, “the One-Eyed”, after sustaining an injury to one of his eyes. Antigonus started as the satrap of Phrygia but quickly expanded his power and influence over most of Asia Minor, Syria and much of the Aegean. By the late 4th century BCE, he and his son Demetrius were the most powerful of Alexander’s successors and, at one point, attempted to reunite the empire under their own leadership.

This aggressive expansionism by Antigonus and Demetrius ultimately led to their defeat at the hands of a coalition of other successors at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BCE. Antigonus was killed in his attempt to hold off his enemies at the age of over 80 while Demetrius was able to flee the battlefield. Their defeat effectively ended any concerted effort to reunite Alexander’s empire after his death. The Antigonid family would be out of power for a time but they were far from finished.

Demetrius Poliorcetes, also known as “the Besieger,” eventually managed to return to power, and his claim was ultimately passed on to his son, Antigonus II Gonatas. Antigonus II would reconsolidate the dynasty’s power over Macedonia around 276 BCE and reestablish Macedonian hegemony over most of mainland Greece. He was also able to weather a variety of military and political threats through a judicious combination of strength and compromise. As such, Antigonus II was able to both maintain the Antigonid dynasty as the ruling house of Macedonia and reestablish their legitimacy with many Greeks.

The Antigonid Kingdom was renowned for its strong military tradition and was frequently embroiled in conflicts with the Aetolian and Achaean Leagues. The Antigonids were often also threatened by external forces, most notably the ever-expanding Roman Republic. Culturally, the Antigonids tended towards pragmatism and were less noted for the ostentatious cultural patronage of the Ptolemies and Seleucids. Pella, the Macedonian capital, became an administrative and military center, but it could not hope to match the artistic splendor of Alexandria or Antioch.

The dynasty continued under several other rulers, including Philip V and Perseus, the last Antigonid king. During his reign, Macedonia became enmeshed in a series of wars with Rome known as the Macedonian Wars. The fate of the kingdom and its royal house would finally be decided after the defeat of Perseus by the Romans at the Battle of Pydna in 168 BCE. Macedonia would be annexed by Rome and the Greek mainland would be drawn fully into the orbit of Roman power.

Despite its ultimate defeat, the Antigonid dynasty played a crucial role in preserving Macedonian autonomy and identity during the chaotic Hellenistic period. The dynasty ruled for almost 150 years and their presence as the dominant power in Greece would often help to counterbalance the power of the larger Hellenistic states or the later expansion of Rome. Although their cultural and political legacy is less well-known than their Ptolemaic and Seleucid contemporaries, the Antigonids were essential figures in carrying Alexander’s legacy into the classical world.

Other Hellenistic Kingdoms and Regions

Kingdom of Pergamon (Attalid Dynasty)

The Kingdom of Pergamon emerged out of the fragmentation of Alexander’s empire. Its founder, Philetaerus, had been a eunuch in the service of one of Alexander’s successors, Lysimachus, who was the ruler of Thrace, Macedon, Asia Minor, and Syria at the time of Alexander’s death in 323 BCE. He revolted against his patron in 282 BCE and took over control of the city of Pergamon (in western Asia Minor), on the borders of Lysimachus’ and Seleucus I Nicator’s domains. He nominally acknowledged Seleucid suzerainty, but the city was effectively self-governing, and his successors ruled as the kings of Pergamon from 263 BCE.

It was under the Attalid dynasty, from Eumenes I to Attalus III, that Pergamon became one of the most civilized of the Hellenistic states. Eumenes’ successor, Attalus I, took the title of king after a successful campaign against the Galatians who had invaded Pergamon. He firmly established the independence of Pergamon and expanded his kingdom’s borders by forming alliances and employing military force, capitalizing on the larger power struggles between the Macedonians and the Seleucids. Pergamon became a close ally of Rome and often aided them in their wars against these powers. The kingdom was relatively small in comparison to other Hellenistic states, but it had significant influence.

Pergamon became a major center of scholarship and a rival of Alexandria. The Pergamon Library had a collection of more than 200,000 scrolls. Pliny the Elder even records that parchment (pergamena in Latin, derived from the Greek word for parchment, περγαμηνά) was developed there to break Egypt’s monopoly on papyrus. Many large-scale building projects were undertaken, including the construction of the Great Altar of Zeus, whose frieze is one of the best-preserved examples of Hellenistic sculpture.

The Attalids are also remembered as good rulers who kept their kingdom from internal strife. They were relatively generous civic benefactors. Most of the constructions, temples, and gymnasia they financed were used to create an urban culture that was very different from the surrounding Anatolian regions and to spread a distinctly Hellenic culture throughout Anatolia.

This is one reason for the high artistic quality and cultural achievement of the Hellenistic kingdom of Pergamon. Attalus III was the last of the line and died without an heir in 133 BCE, leaving his kingdom to the Roman Republic. The Roman Senate peacefully accepted his gift, and Pergamon passed to Rome without incident, bringing it into the orbit of the Roman Republic.

The Attalid dynasty ruled for almost 150 years, and was an enlightened line, remembered primarily for its support of learning and other cultural activities. In a way, Pergamon can stand as the antithesis of the more powerful, forceful successor states of Alexander, whose rule was often more brutal and dynastic. For its peaceful and long-lasting integration into the Roman world, Pergamon can be seen as a success story in its own right.

The Greco-Bactrian Kingdom

The Greco-Bactrian Kingdom was a Hellenistic state which seceded from the Seleucid Empire around 250 BCE, located in what is now Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, and parts of Tajikistan. As the far eastern province of Bactria, it was known for its relative opulence and cultural sophistication. During a period of weakness for the Seleucids, their governor of Bactria, Diodotus I, declared independence and established the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, a Greek-ruled entity far from the Mediterranean center of Hellenistic power.

Economically prosperous and militarily strong under the leadership of Diodotus and his successors, including Euthydemus I, the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom occupied a strategic position on the trade routes between the Greek world, India, and China, including the early Silk Road. Greek-style urban planning was employed, as evidenced by cities such as Ai Khanoum, complete with colonnaded streets, theaters, and gymnasia, leaving a lasting Hellenic mark on the Central Asian urban landscape. Concurrently, local traditions began to blend with Greek influences, creating a unique hybrid culture.

Greco-Bactrian coinage often featured Greek gods but also included eastern motifs, which may have been designed to appeal to local subjects. References in Buddhist texts and archaeological evidence suggest that there were exchanges of ideas and religious practices, especially as later Indo-Greek rulers expanded their territories into the Indian subcontinent. As the Roman historian Justin would write, the Greco-Bactrians were “more powerful than the kings of other nations.”

The Greco-Bactrian Kingdom was also significant in the cultural and intellectual transmission between the East and the West. The expansion of Greek culture into India during the second century BCE led to the creation of the Indo-Greek Kingdoms, where Greek and Buddhist traditions interacted and coexisted. Some Greco-Bactrian kings adopted Indian religious epithets and iconography, reflecting a shift in identity that may have resulted from their geographical and cultural position.

The kingdom persisted until around 130 BCE, when it fell to a series of invasions by nomadic tribes, including the Yuezhi and Scythians. The legacy of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, however, continued through the Indo-Greek successors and the cultural syncretism that they propagated. The Greco-Bactrians had a significant influence on the art, language, and religious practices of the region, showcasing a fusion of Greek and Asian cultures.

In the history of the Diadochi, the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom represents one of the most remote and enigmatic Hellenistic states. It is a testament to the expansive impact of Alexander the Great’s conquests, demonstrating how Hellenism could not only travel but also thrive far from its Mediterranean origins, planting seeds for a cultural heritage that would outlast the political entities themselves.

Ephemeral Kingdoms and Claimants

Not all of Alexander’s generals were successful in their attempts to establish empires. Some, like Lysimachus and Cassander, wielded considerable power for a time but were unable to found enduring dynasties. Lysimachus, one of Alexander’s bodyguards, took control of Thrace and parts of western Asia Minor. His kingdom, characterized by a series of conflicts, was ultimately destroyed in 281 BCE at the Battle of Corupedium, where Seleucus I killed him. His realm disintegrated rapidly and was absorbed by the other Diadochi.

Cassander, the son of Antipater, ruled Macedonia and a significant portion of Greece. Rising to power through the strategic elimination of rivals, he killed Alexander’s widow, Roxana, and their son, Alexander IV, to secure his throne. He declared himself king in 305 BCE, a move that solidified his rule, but his dynasty was short-lived. At his death in 297 BCE, Macedonia plunged into civil war and was soon absorbed by other Successor states.

Eumenes of Cardia was a skilled general and former secretary to Alexander. He fought to maintain the unity of Alexander’s empire. A staunch supporter of the Argead dynasty, Eumenes championed the rights of Philip III and Alexander IV. However, he was ultimately undone by a lack of resources and betrayal. After some initial successes, his troops deserted him, and he was captured and executed in 316 BCE by Antigonus I. His death marked the end of any real hope for a united empire under the old dynasty.

Perdiccas, a member of the regent team after Alexander’s death, attempted to keep the empire intact on behalf of the royal family. His inability to control the ambitions of other generals, particularly Ptolemy, led to his demise. In 321 BCE, he was murdered by his own officers after a failed invasion of Egypt. His death precipitated the unraveling of any remaining unity within Alexander’s empire.

Other individuals, such as Leonnatus and Peithon, also controlled territories but held power for only a short time. Battlefield losses or political machinations often ended their bids for greater influence. While these lesser-known claimants did not leave a lasting mark on the world, their actions and the conflicts they were embroiled in contributed to the prolonged instability of the period.

These ephemeral kingdoms and pretenders, though lacking the long-term impact of the Seleucids or Ptolemies, highlight the chaos and ambition that characterized the years following Alexander’s death. Their stories serve as a reminder that the building of empires in the ancient world was as much about timing and survival as it was about conquest and strategy.

The Legacy of the Diadochi

Beyond just dividing Alexander’s empire, the Diadochi left a long-lasting cultural legacy that outlived their political structures. By ruling over three continents, the Hellenistic culture was expanded from the Mediterranean to the fringes of India. The interaction of the Greek language, art, and government with local traditions defined the Hellenistic Age, which gave rise to a new cosmopolitan identity that endured for centuries.

The major cities, including Alexandria in Egypt, Seleucia on the Tigris, and Antioch in Syria, which were either founded or expanded by Alexander’s successors, became centers of education and commerce. These urban centers, which retained many aspects of the Greek language and customs, were where many influential works of philosophy and science were written. They also fostered trade and industry by attracting merchants, artisans, and scholars from around the world.

The Diadochi’s presence in the former Persian Empire altered architecture and political institutions from Egypt to Bactria. New urban areas were constructed with Greek-style theaters, gymnasiums, and temples. At the same time, the Diadochi also incorporated some of the Persian Empire’s administrative and courtly systems. The resultant hybrid governance not only facilitated the successors’ rule over vast and culturally diverse territories, it also helped them project an image of both familiarity and power. Their rule would later influence Rome, as the emerging empire would gradually absorb many Hellenistic institutions.

Art and sculpture became common under the successors’ rule, with realism and drama becoming a signature of the era. The famous “Winged Victory of Samothrace” and the complex mosaics of Pergamon and Alexandria are examples of the blend of classical Greek form with local subject matter. The public monuments and royal portraiture would also immortalize the divinity the Diadochi often claimed, which they modeled on the deified Alexander.

Arguably, the Diadochi’s legacy most enduring aspect is the widespread use of a common language, Koine Greek, which became the lingua franca of the eastern Mediterranean and Near East. It was used in diplomacy and literature, and would later become the language of early Christianity. This use of a shared language would form the basis for cross-cultural communication over vast distances.

In dividing Alexander’s empire, the Diadochi actually expanded his legacy by spreading Greek culture throughout the ancient world. New kingdoms, cities, and trade routes were created that laid the foundations for the later Roman and Parthian empires. At the same time, the Diadochi’s patronage of the arts and sciences also preserved the intellectual and artistic spirit of the classical world. By rivalling each other, they unintentionally gave the civilization they inherited permanence.