The House of Medici: Banking, Power, and the Birth of the Renaissance

Powerful, influential, and quietly transformative: few families have had such a long and sweeping impact on human history as the Medici. Tracing their origins back to 13th-century Florence as humble wool merchants, they would eventually become Europe’s most prolific patrons of the arts. In doing so, they kick-started one of the West’s most important cultural movements—the Renaissance, an age of innovation, rediscovery, and great beauty and humanity.

Rising from the merchant class and achieving prominence through savvy banking, political alliances, and artistic patronage, the Medici family built the foundations for Europe’s cultural rebirth. Their story is not just one of wealth and influence, but of ideas and creativity. Generations of Medici invested not only in gold and finance, but in philosophy, science, architecture, and art. Florence would become a haven for some of history’s greatest minds, and names like Michelangelo, Botticelli, and Galileo remain synonymous with the city’s creative legacy and the movement as a whole.

Origins of the Medici Family

The Medici ascent can be traced not to their opulent palaces but to the looms and market stalls of medieval Florence. The 13th century saw the Medici family amass a modest fortune from the wool trade, the lifeblood of the Florentine economy. They were regarded as upstanding artisans rather than members of the nobility. However, even at this nascent stage, the family demonstrated a penchant for merging practical business acumen with social aspiration, setting the stage for a grander vision.

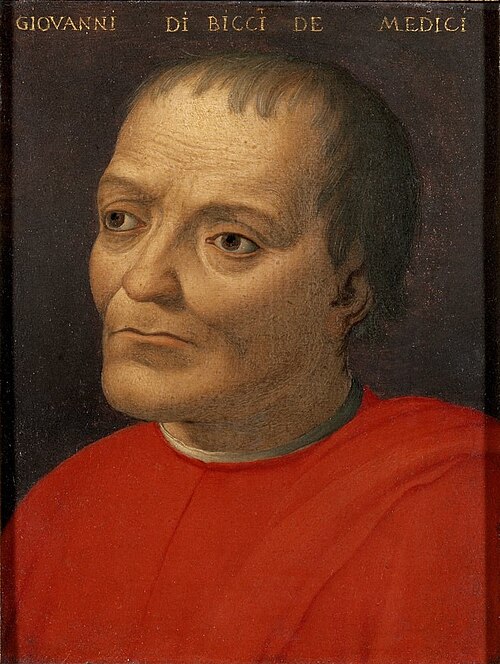

The real shift in the their fortunes came with Giovanni di Bicci de’ Medici, who was born in 1360. An astute businessman with an eye for opportunity, Giovanni established the Medici Bank in 1397. From humble beginnings in Florence, the Medici Bank would rise to become the most influential financial institution in Europe by the mid-15th century. Giovanni’s banking principles centered on expanding trust and dependability, setting the Medici Bank apart from its competitors.

The Medici Bank’s adoption of double-entry bookkeeping, which precisely tracked debits and credits, was a key innovation. This practice provided unparalleled transparency in an era of increasingly complex financial transactions, and it quickly became the gold standard throughout Europe. They also introduced the use of letters of credit, enabling merchants to do business abroad without physically transporting large quantities of cash. This system reduced risk and increased the speed of transactions.

The family’s bank would quickly expand to have branches in major Italian and European cities, including Venice, Rome, Geneva, and London. The Medici Bank’s success was partially due to its alliances with the Catholic Church, particularly with the papacy. Managing the finances of the Catholic Church brought them not just wealth but also proximity to political and ecclesiastical power, elements that would become central to their identity.

Giovanni steered clear of the political limelight, but he employed his wealth to shape Florentine politics subtly, aiding allies in climbing the ranks of power while avoiding direct pursuit of power for the Medici name. He also established a family tradition of intertwining finance and public service, encouraging his sons to support the arts and care for the poor. In this confluence of financial shrewdness and public benefaction, the Renaissance found one of its earliest patrons.

Building Wealth and Influence

The Medici Bank became one of Europe’s most influential financial institutions. Managed by Cosimo de’ Medici, Giovanni’s son, it held accounts for merchants, nobility, and even the Vatican. Their branches across Europe facilitated swift and discreet cross-border transactions, vital in a time of growing commerce and political instability.

The Catholic Church became a significant source of their wealth. Banking for several popes cemented a profitable relationship. In exchange for financial support, the Church provided spiritual validation and political favor. Pope John XXIII was one of many religious figures who became clients and allies. This relationship not only enriched them but also offered protection from rivals, as Medici connections opened doors to the highest echelons of power.

The Medici were not kings, but they ruled Florence as princes. Cosimo de’ Medici, known as “Pater Patriae” (Father of the Fatherland), maintained control without holding an official title. He manipulated the Florentine political system from behind the scenes, funding supporters and swaying councils. According to one contemporary, Cosimo “did more by doing less”—allowing others to take the credit while consolidating power for himself and his family.

Wealth also became a form of public persuasion. The Medici financed public works, church restorations, and city festivals, constantly reminding citizens of their benefaction. These acts of generosity were strategic, creating an image of the Medici as indispensable to Florence’s well-being. Open opposition became politically untenable, as the benefits they provided tied the city’s prosperity to their family’s continued rule.

Monarchs across Europe began to respect the power of the Medici. They came to them for loans and financial advice, further entangling the Florentine family in continental politics. For the Medici, banking was not just about profit—it was about relationships. With gold as their currency and allies in both thrones and miters, they crafted a legacy that reshaped Renaissance politics beyond mere commerce.

Medici Patronage and the Flourishing of the Arts

The most influential members of the family were patrons of the arts and humanism, which were the very sources of the Renaissance’s birth. Cosimo de’ Medici, the dynasty’s first ruler, was a great patron for artists and architects whose work revolutionized the face of Europe. He supported Filippo Brunelleschi, who managed to finish the dome of the Florence Cathedral Santa Maria del Fiore, and Donatello, a Florentine artist, who became known for his sculpture of David made out of bronze, and Fra Angelico, who was known for his frescoes, which showed a subtle spirituality in graceful compositions.

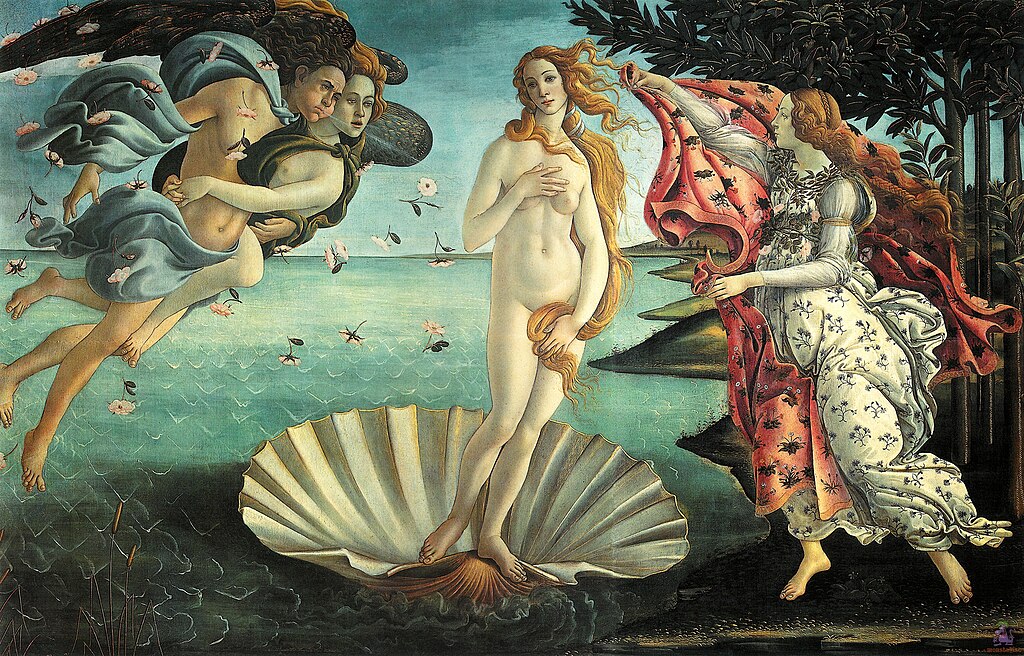

The support of artists reached its climax in the hands of Cosimo’s grandson, Lorenzo de’ Medici, whom history remembered as Lorenzo the Magnificent. Lorenzo, a poet, thinker, and statesman, saw the arts as a way of life as well as a path to eternity. He was the patron of Sandro Botticelli, the artist behind The Birth of Venus and Primavera, which, in a sense, represented the triumph of Neoplatonic aesthetics and perfection. Lorenzo also patronized a young sculptor called Michelangelo, whom he took into his house as a 15-year-old boy.

Leonardo da Vinci also received commissions early in his career, and he was socially well-placed to receive early support and a variety of intellectual stimuli from the Medici’s artistic circle. Lorenzo’s household and court attracted numerous artists, architects, philosophers, and scholars of all types, a phenomenon not commonly found in most courts across the European continent at the time. The resulting cultural flowering and drive to patronize artists and philosophers of the time helped create the Renaissance, which had previously been a spark among intellectuals and an underground movement before Lorenzo’s arrival.

Medici’s funding was indeed not only an act of generosity and a taste for beauty, as art in public places improved their public image; it also strengthened their political position as protectors of the city of Florence and their status as power brokers in the rest of Europe. By sponsoring art and architecture, the Medici helped build Florence into an intellectual and cultural capital of the Western World and an open-air museum, which it remains to this day.

Funding groundbreaking artistic and architectural projects gave artists both the ability and the desire to experiment, as well as the necessary financial support. This was very important in an era when innovation was risky and discouraged by the traditional and often conservative political and religious institutions. The result was a revolution of its own kind: the use of perspective in painting, the quest for naturalism in sculpture, and the introduction of harmony in architecture. All these elements, in one way or another, defined the aesthetics of the Renaissance.

The many masterpieces of the Renaissance period would have remained simply sketches, if not for the vision and intention behind the Medici’s patronage of the arts. They were more than just rich sponsors; they were the architects of culture, creators of beauty, which in its turn inspired generations to come and left a significant mark on the soul of an entire civilization.

Politics, Power, and Papacy

Despite lacking a crown, the Medici exercised power in the republican city of Florence. Cosimo de’ Medici skillfully controlled the city while still maintaining the façade of democratic governance. Through their vast network of loans, patronage, and alliances, the Medici family was able to elect its own city councils without ever needing to seize power. The Florentine historian Niccolò Machiavelli, writing not long after the Medici’s ascent to power, described their influence on city affairs: “He governed by giving and by denying.”

The Medici family was able to grow its power through the influence of the Church. Lorenzo the Magnificent’s son, Giovanni, was made Pope Leo X in 1513, with much pomp and circumstance. The coronation of Leo X as pope was the symbolic and literal high point of the Medici’s political and ecclesiastical influence. The famous Pope Leo X was known for his patronage of the arts and his extravagant lifestyle; his reign was seen as the pinnacle of the Renaissance. It is under Leo X that the Church and family reach their apex of influence and power in Christendom.

Leo is famously quoted as saying, “God has given us the papacy—let us enjoy it.” During his reign, Leo oversaw the Church’s vast wealth, distributing funds to politicians, artists, scholars, and other members of the elite, while also advancing the family’s business interests. Leo X’s cousin Giulio de’ Medici would also become pope as Clement VII, further deepening the Medici family’s connections with the Vatican.

The Medici popes were able to exercise both their political and spiritual influence through their papacy. The family reached its height of notoriety under the rule of Pope Clement VII. However, under his papacy, the family endures its most challenging time during the Sack of Rome in 1527. The Sack of Rome would irreparably damage the image of the papacy, the cost in both money and blood too high.

The Medici popes were able to continue their reign over the Vatican, but the papacy was never quite the same. The family would further attempt to influence the politics of Italy and Europe as a whole through diplomatic marriages, including the marriage of Catherine de’ Medici to the future Henry II of France.

At home in Florence, they were no longer just bankers but titled nobles of the city. In 1532, the Medici family was made hereditary Dukes of Florence by none other than Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. The newly titled family further entrenched their power in the city’s government. Cosimo I, a distant relative of Lorenzo the Magnificent, later rose to power as the Grand Duke of Tuscany, converting Florence into a dynastic principality. The city of Florence, which had prided itself on being a republic, had by this point been turned into a principality by the Medici family.

This is a story of merchants becoming monarchs, a tale of people who start from humble beginnings only to reshape the course of history. The Medici used their political and financial clout to outmaneuver their enemies and rivals, carefully using every tool at their disposal to build their dynasty. Their involvement in banking, the papacy, and politics in Florence has had a lasting impact on the course of history, all by a family of wool merchants.

Cultural Legacy and Contributions to Humanism

The Medici influence extended into the intellectual life of the Renaissance through the humanist movement. Emphasizing education and secular concerns, humanism originated in the 14th century. Cosimo de’ Medici played a key role in the development of the Medici Library, one of the most significant collections of manuscripts in Europe. He also supported Marsilio Ficino, who founded the Platonic Academy in Florence. The Platonic Academy was an influential institution that was dedicated to translating and reinterpreting ancient Greek philosophy, particularly that of Plato.

Cosimo de’ Medici was also a major supporter of humanist philosophy in general. The Medici supported the efforts to search out and rediscover lost classical texts throughout Europe and the Middle East. The recovery of classical learning, sponsored by the Medici, led to the translation of many of these new-found texts from Greek and Arabic into Latin. As a result of these efforts, many of these works became available to a new generation of scholars. Lorenzo the Magnificent’s patronage was influential in this period of intellectual “revival”. Lorenzo’s circle of intellectuals, including Pico della Mirandola and Angelo Poliziano, supported the idea of human beings having free will and the ability to create their own destiny.

This focus on humanism was a central element of education in Renaissance Europe. This new humanist approach to learning spread from Florence to universities and royal courts throughout Europe. The Medici’s focus on humanism transformed the education and training of the intellectual elite. Subjects such as rhetoric, history, philosophy, and the arts were seen as particularly important. They had applications to subjects considered more practical than the study of divinity and theology. These disciplines also emphasized the individual’s potential and the importance of participating in civic life. This intellectual and educational legacy laid the essential foundation for the Age of Enlightenment, which developed centuries later.

The family was not only crucial as patrons of the arts and intellectuals. They were also collectors and conservators of knowledge and culture. The Medici libraries played a vital role in preserving ancient texts and documenting the history of the Renaissance. The Medici academies were also influential. Their encouragement of new ways of thinking was central to the development of an intellectual environment that was creative, innovative, inquisitive, and expressive. The Medici can therefore be seen as providing an essential philosophical foundation for Western civilization.

In the political arena, they were pragmatists. In the cultural arena, they were visionaries. The Medici investment in humanism was more than a mere act of self-aggrandizement. It was part of an effort to create a legacy that was the basis of the brilliance, the beauty, and the intellectual inquiry that is associated with this time period. In their support of the great minds of the day, the Medici made Florence more than a city—it made Florence the birthplace of an age.

Decline and End of the Dynasty

The Medici’s vast power was not to last indefinitely. By the end of the 16th century, the family’s banking dynasty, once Europe’s most influential, had declined. A combination of financial mismanagement, risky loans, and competition contributed to the weakening of their fiscal might. Internally, the rise of the Medici had sown discord among other powerful Florentine families, while their absolutist rule began to chafe the public.

They transitioned from being influential backers to outright monarchs, a change that increasingly left them exposed. In 1569, the Grand Duchy of Tuscany was established, raising the family’s status to that of royalty and binding their fortunes to the dynastic struggles of Europe. With the death of Gian Gastone de’ Medici, the last Medici ruler, in 1737, the line was effectively extinguished as he left no heirs. The family’s Medici line ended and Tuscany was absorbed by the Austrian House of Lorraine.

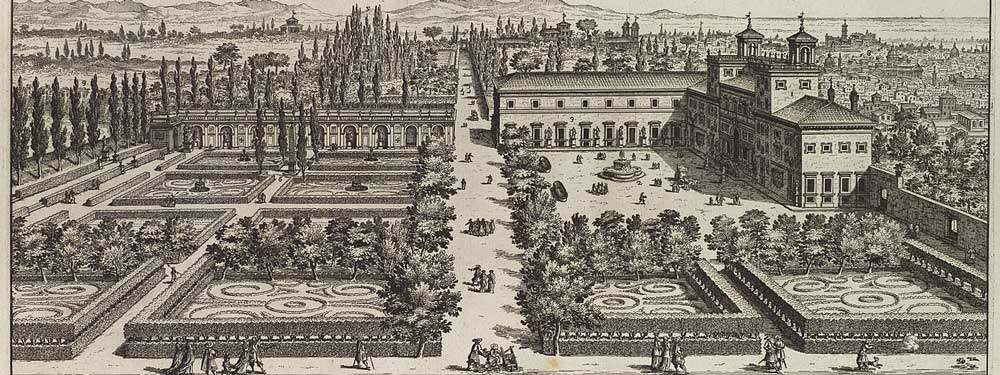

Yet, their impact on Florence and the world did not fade with their political decline. The Uffizi Gallery, built initially as offices by Giorgio Vasari, has become one of the most important art museums globally, housing a collection of artworks commissioned or acquired by the Medici. The Medici Chapels are lavish sepulchers that remain as lasting monuments to the grandeur and ambition of the Medici lineage.

Palazzo Medici-Riccardi is among the earliest Renaissance structures in Florence, a testament to the family’s taste and influence. Designed by Michelozzo for Cosimo the Elder, its restrained style set the standard for palatial architecture in the region. These edifices, alongside numerous paintings, sculptures, and manuscripts, are testaments to the Medici patronage that helped shape the Renaissance era of art and power.

In the end, the Medici could not defy the mortality of their dynasty. But few families have stamped themselves so indelibly upon the canvas of their era. Their legacy, while no longer political, persists through the art they championed and the institutions they inspired. It is woven into the very DNA of the Renaissance they helped kindle.

A Legacy Written in Marble and Manuscript

The secret to the Medici’s success lies in their ability to wield power effectively. An independent country with a voracious appetite for trade and a national obsession with finance, it was the Medici who took full advantage. They began life as unassuming wool merchants and, by the fourteenth century, had positioned themselves as Europe’s most prominent bankers. They utilized their knowledge of finance to acquire influence not only in Florence but also in the papal courts and royal dynasties of Europe. Their legacy, however, was not built solely with money; the Medici used their fortune to underwrite human creativity. Through the art, architecture, scholarship, and science they funded, the Medici supported some of the most iconic names in history.

The family has a complicated legacy as patrons of humanism and leading purveyors of oligarchy. Their legacy is one of both Enlightenment and repression, cultural rebirth and dynastic ambition. Nevertheless, the world they had helped create and define continues to resonate through the museums, libraries, and governments of Europe. The Renaissance spread throughout the continent but had its most powerful, pulsating heart in the city of Florence under the Medici.