The Rise of a Patriot: William Wallace and the Struggle Against England

William Wallace was born in the midst of a crisis that would change Scotland forever. For centuries, the Scots had been a proud, independent people. By the end of the 13th century, Scotland was at its lowest ebb. King Alexander III had died in 1286. He had only one heir, a granddaughter, known as the “Maid of Norway”. She was 4 when her grandfather died, but she also died en route to Scotland to take up her throne.

This left the Scottish throne empty and led to a power struggle between several claimants. The most influential of these was Edward I of England. At this time, the English king was known as “Longshanks”. He took advantage of the situation to claim overlordship over Scotland, and the Scottish nobles submitted to him, doing homage to the King of England. Scotland was now occupied and ruled by an English king; its nobles expected to pay taxes to Westminster, and the country was in disarray and crisis.

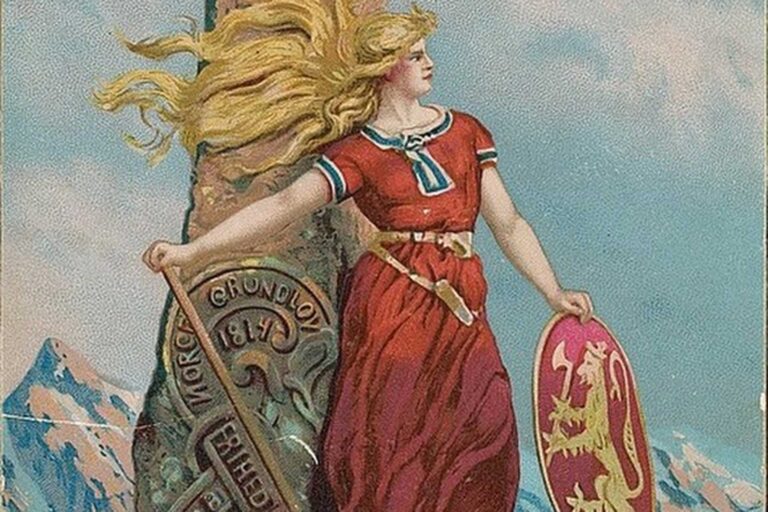

Into this world, at this critical juncture in Scottish history, came a man to change the country’s fortunes and galvanize a nation. William Wallace was a man of humble birth, but he took up the cause of liberty and became a symbol of Scottish independence. His resistance to the English occupation, his patriotism, his victories, and his eventual martyrdom were to fire the rebellion that created Scotland as we know it today.

Scotland Under English Rule

Margaret, the “Maid of Norway,” was the only surviving heir to King Alexander III. After her death in 1290, the Scottish throne was left vacant, with no clear heir. Thirteen claimants to the throne emerged, and a period of power struggle ensued. In order to prevent a civil war, the Scottish nobles asked Edward I of England to arbitrate, to which Edward agreed on one condition. He demanded to be recognized as Scotland’s feudal overlord. The Scots had no choice but to agree, and in the following process known as the “Great Cause,” Edward chose John Balliol as King of Scots. He was enthroned in 1292, but his authority was never fully respected.

Edward humiliated Balliol at every opportunity. He treated him as his subject and forced him to swear allegiance to English law. When the King of Scots sought to challenge his judgment, he was summoned to London to answer before an English court. His final indignity was to be ordered to send men to fight for England in a war against France, a demand his countrymen viewed with outrage. Scotland had long regarded itself as an independent nation, and for Edward to expect them to take arms as his subjects was an affront too far.

Resistance to Edward began in earnest in 1296. After several demands to stop the Franco-Scottish alliance, he marched his army north and laid waste to the country. The town of Berwick was sacked and almost all of its inhabitants put to the sword. In less than two months, his forces had crushed the uprising and captured the king. Balliol’s throne was dismantled, and he was stripped of his royal insignia and imprisoned. Edward had assumed the throne for himself and installed English governors and garrisons at the key sites. He had Scotland under his heel, and many saw him as the “Lord Paramount of Scotland.”

English officials began to pillage the land, taking much of it for themselves. Taxes were levied at an unprecedented level, leaving farmers and merchants with little. Scottish strongholds were taken over by the English garrisons, and the people no longer felt safe in their homes. The legal system was no longer independent, with Scottish cases tried by English judges. To ordinary Scots, it was an occupation in all but name, and resentment towards the English was growing.

Chroniclers of the day write of “a yoke upon the neck of Scotland,” and many Scots would have agreed. Men and women of all classes felt their nation had been stolen from them. Many dreamt of freedom and independence, and in the dark days that lay ahead, some would resist. The Scottish people would not be overthrown without a fight, and someone would have to rise and lead them in battle. The name of that leader would be William Wallace.

The Making of a Rebel

The exact circumstances of Wallace’s birth are murky at best, with the written accounts being sparse and largely influenced by legend. Nonetheless, what evidence we do have suggests he was born around 1270, likely in the vicinity of Elderslie or in the broader Ayrshire region. The son of a lesser noble or landholder, Wallace was educated, literate in Latin, and trained in the arts of swordsmanship and tactics.

The English, meanwhile, were tightening their grip on Scottish affairs. Independence and self-determination were not abstract concepts to William Wallace, and as English garrisons were installed and national pride was mocked and trampled, patience waned. For men of freeborn Scottish blood such as Wallace, the personal affront of occupation and the call to reclaim their land from foreign rule would have felt both personal and immediate.

His initial act of rebellion, the one for which Wallace first made history, came in the town of Lanark in 1297. Wallace killed the local English sheriff, William Heselrig, allegedly in revenge for the murder of his wife or female companion. Wallace’s personal grievance became the spark for revolt. Murder in the eyes of the English, defiance in the eyes of the Scots.

News of Wallace’s actions spread rapidly through the land. Local skirmishes broke out in the surrounding countryside, and many began to realize that not all who resisted Edward were highborn nobles or grand armies—ordinary men could take up the cause and be free.

Wallace had struck at a time when Scottish nobles were still reluctant to openly defy the English, still stung by the recent deposition of John Balliol. But if the nobles lacked the will, Wallace had the conviction and sense of justice to lead. He began organizing small raiding parties, using his knowledge of the local terrain and guerrilla tactics to strike at English outposts and supply lines. Wallace was not yet a general or a king, but he was a beacon of hope to the Scots. In a time of uncertainty, his actions and growing reputation served to galvanize support and unify various pockets of resistance.

Legend and chroniclers have since painted him as a man of formidable size and indomitable spirit, while English records decried him as an outlaw and a traitor. To the common Scotsman, however, Wallace became a symbol of resistance, embodying both the anger and hope of his people. He fought not for riches or power but for freedom, a notion that resonated across class and clan divisions.

By the middle of 1297, Wallace had transcended local rebellion, becoming a symbol of a nascent national movement. The isolated uprisings of 1297 were now crystallizing into a united front, a coordinated resistance against English oppression. From the murder of a single sheriff, a revolution had been sparked, one that would soon culminate in open warfare, a battle for the very soul of Scotland, and the forging of a legend whose name would be known for all time.

The Battle of Stirling Bridge (September 1297)

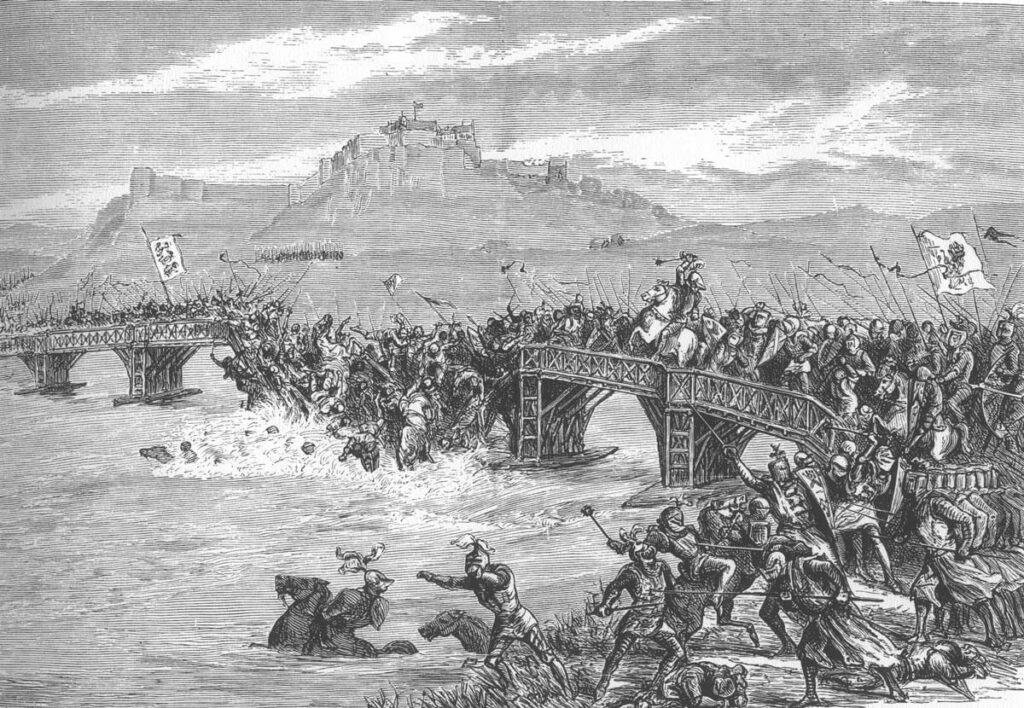

England had little tolerance for the ongoing rebellion in Scotland by the end of summer 1297. Edward I’s tax collectors and administrators in Scotland, Hugh de Cressingham and William de Warenne, gathered together an army. Led by Cressingham and Warenne, this English army, numbering around 10,000 men, advanced to crush William Wallace and the rebel Scots. In terms of numbers and equipment, the English had a significant advantage.

However, they were largely marching into unchartered territory. The Scots under Andrew Moray and Wallace were not lacking in bravery, but they were heavily outnumbered and much less well-equipped than their enemy. The Scottish rebels did have one important advantage, and it lay in their cunning, discipline, and knowledge of the local area.

Wallace and Moray gathered their men near the city of Stirling, where the River Forth was only wide enough to cross at a narrow wooden bridge. The Scots did not challenge the English directly across the open battlefield. Instead, they displayed a remarkable degree of patience. They waited until a portion of the English force had crossed the bridge and was isolated from the rest. At that point, with a loud and fierce war cry, Wallace’s men charged into the unsuspecting English ranks.

The narrow bridge prevented English reinforcements from crossing to aid those trapped on the other side, who had no option but to fight to the death. Chroniclers noted that the river “ran red with English blood as one sank under another.” Men were so weighed down by their own armour that many drowned.

Hugh de Cressingham, who was Edward’s treasurer in Scotland and one of Wallace’s most hated enemies, was among the English dead. Legend would have it that his skin was flayed and used to make a sword belt. Thousands of English troops were killed or wounded while Scottish losses were few. The battle of Stirling Bridge had a profound effect. The myth of English invincibility was destroyed in one fell swoop.

National pride was at a high point as never before in Scotland. Wallace was naturally a hero of the victory. When Andrew Moray died of his battle wounds, Wallace became the unchallenged leader of the rebellion. He was made Guardian of Scotland and ruled in the name of the deposed King John Balliol. Wallace organized the Scottish defences, boosted morale, and re-established their independence against a vastly more powerful foe.

The victory at Stirling Bridge showed that unity, cunning, and strategy could overcome superior force and numbers. It was a moment of vindication for a people that had long been humbled by foreign oppression. For Wallace it was the pinnacle of his power. For Scotland it was the birth of a belief that freedom was worth the fight, even if that fight came at a price.

Guardian of Scotland and the War’s Turning Tide

The success of Stirling Bridge was followed by a period when Wallace was at the peak of his power. Andrew Moray’s death left Wallace as the single Guardian of Scotland, and he was invested as regent for King John Balliol. For the first time in several years, Scotland had a ruler who was both feared and respected by all, a ruler who could keep the clans, the nobility, and the people united. Wallace bolstered defenses, rallied the army, and began to reach out for foreign alliances. He knew that to preserve Scotland, he must fight not only on the battlefield.

In 1298, Wallace sent emissaries to France in an attempt to gain the support of King Philip IV. In his letters (written in Latin), Wallace made a strong case for Scottish independence, presenting his country as a nation which had been unprovokedly attacked by its English neighbor. The Scottish moves were some of the earliest indications of foreign policy in the country, and they reflect Wallace’s political awareness beyond the immediate battlefield. While Wallace tried to win over allies in France, Edward I was already mobilizing a full-scale invasion of Scotland. The English king led the massive army north personally. Edward I was determined to avenge the disaster at Stirling, and to end the rebellion decisively.

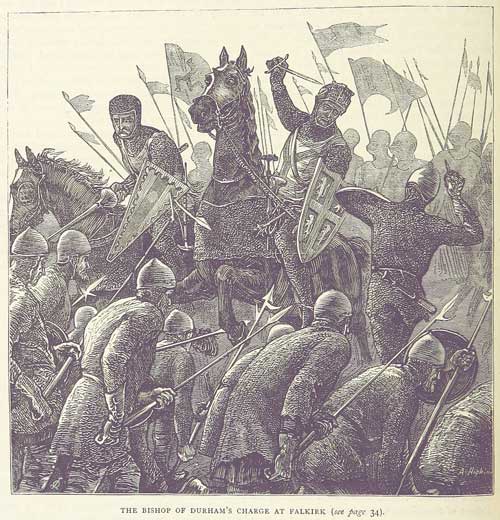

The Battle of Falkirk in July 1298 was the result. Wallace used a defensive strategy, setting up schiltrons: circular formations of spearmen intended to repel the English cavalry. The plan had some success initially, but ultimately, the English longbowmen turned the tide. One volley of arrows after another broke up the Scottish formations, sowing panic and rout. The Scottish cavalry had deserted the field early in the battle, leaving Wallace’s infantry to face the English army on its own. Wallace fought hard to maintain order and avoid a total disaster, but by the end of the day, thousands of Scots lay dead, and the rebellion had been crushed—at least for the time being.

Wallace resigned as Guardian in the aftermath of Falkirk, but he remained a potent symbol of resistance. The way he had held a country divided by many interests together under immense pressure had made him a legend. Chroniclers of the time remarked his dogged determination and his refusal to yield, even when faced with overwhelming force. “He loved better to be free than to be rich,” as a contemporary put it.

Wallace’s actions at Falkirk may have marked the beginning of the end of his direct military involvement in Scotland’s affairs, but they did not signal the end of his influence. His time as leader had turned Scotland’s resistance into a national struggle. Even in defeat, Wallace had shown that a desire for independence could not be put down by military might alone—a fact that neither he nor Edward I would outlive.

William Wallace’s Capture and Execution (1305)

It is believed that after the crushing defeat at Falkirk, Wallace was able to slip away into the wilds of occupied Scotland and disappear. For years, he lived as an outlaw, but he still managed to harass the English with guerrilla tactics. Some accounts suggest he left the country altogether, possibly France, to renew support for the Scottish cause in the court of Philip IV. Whether or not he was successful, his name was still whispered in the north with a mixture of admiration and hope. To the English, he was a wanted traitor and thug, and Edward I would never forgive the man who had so insulted and bested him.

In 1305, Wallace’s freedom came to a sudden end by the act of treachery. Sir John de Menteith, a Scottish knight, captured Wallace in the open near Glasgow and betrayed him to the English in exchange for a reward. The hands of Wallace were bound together, and he was kept under a strict guard as he was moved south toward London for a public display of the defeated outlaw.

Crowds flocked to the chance to catch a glimpse of the “outlaw of Scotland,” and he was carried through the streets of London by jeering onlookers as an embarrassment to the country. Still, he was brought before the court in Westminster Hall, and when asked to kneel before King Edward, Wallace refused. In the face of death, his confidence was unshakeable.

Wallace was charged with treason against the crown, but he denied that he owed his allegiance to Edward and his regime at all. “I could not be a traitor,” he would say, “for I owe him no allegiance.” His words brought the hypocrisy of the trial into focus. In the eyes of the English, he was a felon and murderer. To the Scots, he was a patriot and the true defender of his country, a man who had never sworn allegiance to a foreign ruler.

It was already a foregone conclusion; there was no chance for Wallace to defend himself. He was condemned to the most gruesome of deaths, a death not only meant to kill, but to destroy his reputation in the process.

On August 23, 1305, Wallace was dragged through the streets of London, then hanged but not killed, disemboweled, beheaded, and quartered. His head was spiked on London Bridge, and his limbs were sent to Newcastle, Berwick, Stirling, and Perth to serve as a warning to others who might think of rebelling. The result was the exact opposite of what Edward I intended, though. The cruelty of his death only solidified Wallace’s reputation and legacy.

The death of William Wallace would spur on his legacy as a hero for centuries to come. Within a generation, Wallace’s dream of an independent Scotland would be realized through the efforts of Robert the Bruce. In the end, the man who had been thought an outlaw by his country’s enemies became a patriot, a symbol, a martyr, and the very face of a nation.

Legacy of William Wallace

Wallace’s execution was intended to crush the Scottish spirit, but it did the opposite. His final words and gallant defiance in the face of torture and death became legendary. A new generation of Scots rose to carry on his cause, and within a few years, Wallace’s standard was being held high by Robert the Bruce. The flame of freedom was once more fanned by conflict, and the independence movement found new purpose. The cry for freedom that Wallace made his own still rang through the land. His martyrdom became the foundation for the eventual rekindling of the Scottish cause.

The Bruce went on to victory, and in 1314, at the Battle of Bannockburn, Scotland’s greatest triumph, his forces overcame Edward II and his vastly larger army, securing Scotland’s independence for a generation. Wallace did not live to see it, but for many of those who knew him, that was the moment his vision became reality- a free and proud Scotland standing up to the forces of tyranny. Chroniclers wrote that it was “the seed of liberty that Bruce sowed and reaped in glory,” which was planted by Wallace’s martyrdom.

Beyond his military campaigns, Wallace became a lasting symbol of freedom and national identity for the Scottish people. To the Scots, he embodied the unbreakable spirit of defiance against oppression. His name became synonymous with the concept of resistance to foreign rule. For generations of patriots, Wallace was more than a warrior; he was the living spirit of Scottish independence, an ordinary man who became a champion of his country’s dignity.

Wallace was commemorated in song and story for generations after his death, the most famous of which is Blind Harry’s 15th-century epic poem The Wallace. In it, the author transformed Wallace into a near-mythic figure, a man larger than life and embodying all that was best in Scottish courage and righteousness. Several centuries later, a movie reawakened the world to Wallace’s story. Braveheart (1995) retold the legend, but not always accurately. Still, the film carried the same emotional truth of Wallace’s life: “Every man dies, not every man really lives.”

Wallace lives on in Scottish memory as one of the country’s most venerated heroes, a symbol of courage, sacrifice, and national pride. A monument to Wallace towers over Stirling, overlooking the fields of Bannockburn. More than seven centuries later, his name still rings in the heart of a nation, reminding them that the fight for freedom is the most human struggle of all.