Thomas-Alexandre Dumas: A Life of Daring and Glory

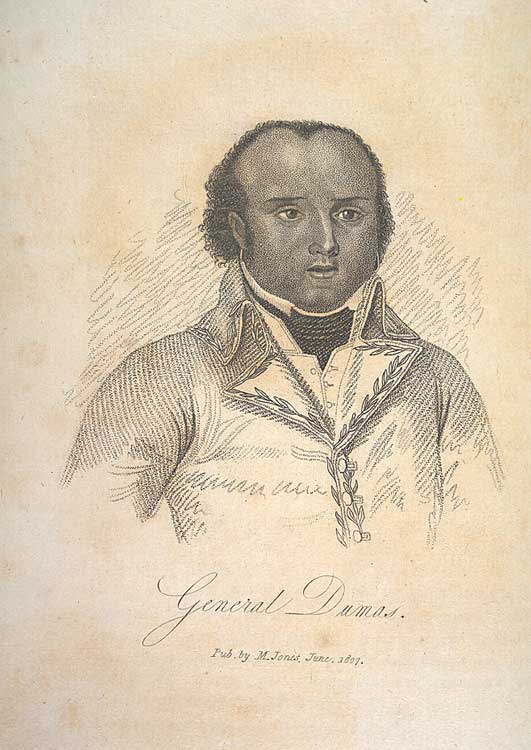

Thomas-Alexandre Dumas was born the child of a white French nobleman and an enslaved woman in the French colony of Saint-Domingue (modern-day Haiti). Dumas would overcome the humble beginnings of his life to become a general in the French Revolutionary Army, fighting in some of the most significant conflicts in modern European history. Known for his personal courage and a sense of justice, he would become beloved by his men and regarded with suspicion by a future emperor, Napoleon Bonaparte.

Dumas’ life was one of the most adventurous and daring in French history, taking him from the plantations of the Caribbean to the heights of the Alps in the company of the foremost armies of his time. Marked by acts of great personal valor, a principled opposition to tyranny, and the crushing weight of political betrayal and historical obscurity, Dumas was a testament to the revolutionary spirit and the power of human will.

Origins in Saint-Domingue

Born in 1762 in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, now Haiti, Thomas-Alexandre Dumas was the son of Alexandre Antoine Davy de la Pailleterie. Dumas’s father was a minor French nobleman. He had moved to Saint-Domingue to escape money problems in France. There, he had purchased and later fathered a child with an enslaved woman named Marie-Cessette Dumas, who was of African descent. This was Thomas-Alexandre.

Dumas’s childhood years were spent on the plantation where his mother worked. He came of age in a society built on slavery and often was witness to its worst excesses. He was, however, recognized by his father, who better treated his son than many children born to slaves. When Dumas was in his mid-teens, his father made the decision to return to France, and, somewhat unusually for his time and social status, freed his son and brought him along.

Slavery was not recognized as legal in mainland France at the time, so the young man could live as a free person there. He took the name Dumas, his mother’s name, rather than his father’s noble name. (It is not clear if this is because he was proud of his mother or if he did not want to use his father’s name because he was a slave.) The young man Dumas was introduced to French society and a European education. He was in for a radical change, from being born on a slave plantation to being reared in Europe as a free young aristocrat.

Early Life in France

As a child of a white French nobleman and a Black enslaved woman, Dumas grew up as a free man of mixed race in 18th-century France, a time when, though legally free with all the privileges of French citizenship, racial discrimination persisted. France was not free of racism, but for Dumas, it was a land of opportunity. He was schooled in the classics and became a natural athlete, excelling at fencing, which became one of his most enduring legends.

The young man, who adopted the name “Alex Dumas,” joined the Queen’s Dragoons at 24. Dumas’s height—he stood over six feet—impressed the officers, as did his imposing bearing. In the military, his martial talents, courage, and leadership quickly became evident. When the Revolution began, Dumas was in the right place at the right time. As officers of the nobility began to flee, he remained and, as was now the norm, began to make his way up the ranks based on merit alone.

By 1793, he was a general, one of the highest-ranking military leaders of Revolutionary France and, arguably, the first Black person in modern European history to hold such a rank. On the battlefield, Dumas was known for his courage and cunning. His adversaries gave him the nickname of “the Black Devil,” and his superiors took note. Dumas, a man at the right place at the right time, personified the new republic, full of fire, ideals, and audacity.

Revolutionary War Hero

Thomas-Alexandre Dumas became one of the Republic’s most ardent and indomitable commanders during the French Revolutionary Wars. He took up arms to fight for the ideals of liberté and égalité and was known to lead the charge in some of the Revolution’s most arduous campaigns. Dumas’ tactical acumen and fearless valor endeared him to both soldiers and citizens alike. He is often remembered for leading cavalry assaults through snow-covered Alpine passes, shoring up the line, and turning the tide against enemy troops in enemy territory.

His military feats in the Alps were nothing short of legendary. In one instance, Dumas reputedly dismounted from his horse mid-battle to wrestle a cannon into place, preventing a full retreat of the line—his herculean strength and daring left onlookers aghast. In Italy, he led successful operations against the Austrians and frequently placed himself at the forefront of the lines. He gained a reputation as both a formidable swordsman and a towering figure, earning him comparisons to the heroes of old. As one officer once noted, “He was more than a general. He was a force of nature.”

However, it was not just Dumas’ physicality that set him apart. He was also a fierce proponent of the Republic’s egalitarian principles, known to voice his opposition to aristocratic privilege even at great personal cost. He was popular among the rank and file for his willingness to share in the hardships of war and was seen as a champion of equality before the law. Dumas took to his military career not as a means to further his power, but to staunchly defend the Revolution’s principles.

In 1794, Thomas-Alexandre Dumas was appointed General-in-Chief of the Army of the Alps, leading thousands of troops on a long and mountainous frontier. He was the first man of African descent to ever command a major army, let alone to reach the highest generalship in a Western army—an incredible accomplishment given the prejudice of the age. This was not a token appointment or honorary title. Dumas had seized it through audacity, martial prowess, and a near-obsessive drive for justice.

The general continued to fight honorably and capably in the face of shifting political winds, never straying from his moral code. His decisions on the battlefield were often swift and decisive, but he showed a commitment to saving civilian lives and preventing unnecessary bloodshed wherever possible. For many, he was the epitome of the citizen-soldier, fierce in combat but principled and restrained.

In the tumultuous era between the Revolution and the rise of Napoleon, Thomas-Alexandre Dumas embodied the revolutionary spirit, serving the Republic as a soldier and role model. He had surpassed the expectations of a lifetime, toppling precedent and leaving behind a legacy of heroism, valor, and fortitude that would one day inform the works of his son, Alexandre Dumas, the world-renowned novelist.

Clash with Napoleon

The careers of Thomas-Alexandre Dumas and Napoleon Bonaparte became intertwined in Egypt, and for a time, they collaborated as revolutionary generals. During the campaign, both commanders established reputations as daring and brilliant soldiers. Dumas and Bonaparte initially got along well, with the former showing great respect for the latter and Napoleon responding in kind.

The men were both a generation younger than the other commanders, and Dumas, as one of the expedition’s highest-ranking officers, was crucial to its success. He had been placed in charge of the cavalry, and his initial successes against the Mamluks were instrumental in the campaign’s early phase. However, as their time in Egypt went on, the fundamental differences in their worldviews became clear. Napoleon, driven by a desire for personal power and autocratic rule, began to drift away from the republican ideals that had once united him with Dumas. The latter, on the other hand, remained true to his republican principles and found himself growing increasingly disillusioned with the conduct and leadership style of his former friend.

Dumas was perturbed by the treatment that Napoleon and his officers were giving to the local populations and by his swift assumption of authority. While Napoleon was busy consolidating his rule, Dumas, who had served the Republic above all else, could not remain silent. He was the one to voice concerns about the megalomaniacal cult of personality that Napoleon was beginning to create around himself. While Dumas’ stand was an act of great personal courage, it was also politically risky. He was, by many accounts, one of the only high-ranking officers who were not afraid to confront Bonaparte about his increasingly authoritarian behavior.

The exact events that led to the final break between the two are unknown, but there is reason to believe that Dumas’ refusal to kowtow to Bonaparte’s whims was the final straw. There are even suggestions that Bonaparte saw Dumas as a threat, not just because of his rank and popularity among the troops but also because of his outspoken republicanism and his racial background. During a period when the French military was becoming increasingly hierarchical and less tolerant of diversity, this was a significant issue. Whatever the case, Dumas soon requested permission to return to France, which, to many people, seemed like a resignation in protest.

In 1799, he left Egypt on board a ship that was wrecked along the Italian coast. Dumas was captured by Neapolitan forces and imprisoned for almost two years. He spent this time in a dungeon without a mattress and was almost entirely forgotten by the French government. Napoleon, who by then was busy consolidating his power in Paris, did not extend any aid to his former comrade. Ironically, one of the Republic’s most celebrated generals was left to rot in a foreign dungeon while his former commander and enemy was paving the way to becoming an emperor.

The imprisonment took a heavy toll on Dumas’ health and seems to have been the cause of his permanent invalidism. When he was finally allowed to return to France in 1801, it was as a broken man. Weakened by malnutrition and constant illness, his rank, military record, and previous status had all done little to help him either with the new imperial authorities or with the restoration of his health. Dumas had served the Republic with unmatched heroism and died still loyal to its cause. Ultimately, the clash with Napoleon had cost him his health, career, and reputation.

Capture and Imprisonment

In 1799, after separating from Napoleon during the Egyptian expedition, Dumas embarked on a ship to return to France. En route, the ship was forced to stop at the Italian port of Taranto, which was under the control of the Neapolitans. Hostile monarchist authorities arrested Dumas, who was a general of the French Republic, a man of color, and a vocal critic of tyranny. Left without diplomatic support or intervention from the French government, Dumas was imprisoned without trial.

He was held captive in the Kingdom of Naples for over two years in one of the most notorious prisons in the region. He was subjected to inhumane conditions, including starvation, disease, and psychological torture. In a letter from prison, Dumas appealed for help, “I am perishing here.” Dumas’ entreaties went unanswered. The French government under Napoleon did nothing to help secure his release. This was probably due to their estranged relationship.

When Dumas was finally released in 1801, his previously robust health was beyond repair. He returned to France physically and financially broken. Despite his previous service as a general of the revolution and commander of the Army of the Alps, Dumas received no pension or public acknowledgment. Napoleon, who had become First Consul, turned a deaf ear to Dumas’ pleas for assistance, leaving him politically ostracized and without the means to rebuild his life.

His homecoming was the beginning of a long, quiet decline. Once celebrated as one of France’s most daring military leaders, Dumas now found himself sidelined as the nation became increasingly entrenched in Napoleonic loyalty. The betrayal was a bitter pill to swallow. In many ways, the prison walls had followed him home. He remained an outsider in the new imperial order, his legacy ignored, his courage unrewarded.

Despite these many challenges, Thomas-Alexandre Dumas never wavered in his belief in the principles of liberty and equality that had defined his life and career. His suffering became a testament to the price of political conscience in an era of rising authoritarianism. Imprisonment is one of the darkest chapters in Dumas’ life, but it also highlights his moral strength. Even in the face of abandonment and betrayal, Dumas never compromised his principles.

The man who had commanded armies and defied monarchies was now at war with illness and obscurity. But in time, his legacy would be reborn – not just in the annals of history, but in the works of his son, Alexandre Dumas père. The great author transformed the stories of honor, courage, and betrayal into the very fabric of French literature.

A Hero Forgotten

Thomas-Alexandre Dumas died in obscurity. An invalid and nearly penniless, he lobbied fruitlessly for vindication from history. The end came in 1806: Dumas was just 43 years old when he died at Villers-Cotterêts. There were no military honors at his funeral, no remembrances of his generalship. No public statue or posthumous ceremony from the state that he had served so well. Official France had forgotten its black general, or never remembered him at all. Dumas became an exile in death from a Republic he had fought so bravely to protect.

The most significant impact was felt, of course, by Marie-Louise Labouret, who had become Dumas’ wife. Widowed, without a pension, without means, the labors of supporting herself and her young son, Alexandre, would be hers alone. The struggles of both mother and son in these years were real and constant. They would live together on meager earnings, sometimes on the charity of friends, sometimes on the edge of abject poverty. The work of preserving her husband’s name and reputation was hers alone.

His son was Alexandre Dumas, the renowned novelist, best known for his works The Three Musketeers and The Count of Monte Cristo. He would write rarely of his father, but the black general lives in the works of his son: in the characters of d’Artagnan and Edmond Dantès, in their courage and endurance, their betrayals, their legendary feats, their passionate, relentless idealism. If the general did not live on in military glory, he lives in the imaginations of men.

But to remember the life of Thomas-Alexandre Dumas is to see that his tragedy was not only in his failure to cling to power. It was also, and perhaps more so, in his erasure from a history he had helped create, a hero of both the battlefield and the Republic’s principles cast aside by the politics, the color, and the inconveniently high-minded principles of others. In some ways, he remains an inspiration even now, two centuries after his death. A life of resilience in the face of injustice, a legacy reclaimed not by governments but by storytellers.

Legacy in Literature and History

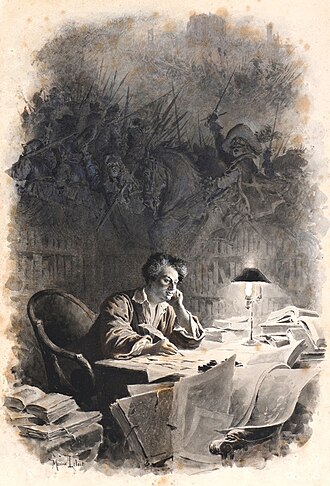

General Dumas’ truest and most enduring legacy is not to be found in any archives but in the legend of his son, author Alexandre Dumas père. When his father died of a disease at age 46, Alexandre was just a boy of four. But his mother and grandparents kept his memory alive for him in stories, and he had plenty of time to dream of his father growing up.

And the fantasies of a precocious and wildly imaginative child became the masterworks of one of the most prolific and popular French authors of all time. The life of Thomas-Alexandre Dumas has inspired generations of readers to wonder what kind of mind could create Edmond Dantès, or d’Artagnan. And more and more scholars have agreed on the answer: the same man who fought for France in the Alps and Italy.

In recent years, historians have started to right the record. From near obscurity, General Dumas is slowly reemerging as one of the most brilliant French generals of the Revolutionary period, if not the most brilliant. His military achievements in the Alps and Italy, his principled opposition to authoritarianism, and his meteoric rise from slave to general are studied by French military historians as extraordinary examples of military and moral leadership. Tom Reiss, the author of The Black Count, sums up the case for Dumas’ legendary status: his life story is “an epic adventure that somehow escaped the history books.”

The French state did not remember Dumas for nearly 200 years. In 2002, however, the Fifth Republic atoned for its neglect. In a symbolic reburial at the Panthéon in Paris (a mausoleum reserved for France’s national heroes), Dumas’ remains were interred, and a statue of a man emerging from chains was unveiled to honor his birthright. Jacques Chirac, then president of the Republic, proclaimed to the assembled crowd: “General Dumas, you enter the Pantheon with justice and with the recognition of the Nation.”

Today, streets, squares, statues, and schools bear the name of Thomas-Alexandre Dumas, especially in his birthplace of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) and across France. In the coming years, we can only hope that his biography will continue to encourage a discussion on race, colonialism, and historical memory not only in France but around the world. As the son of a slave and a noblewoman, a soldier and a statesman, a rebel and a patriot, Thomas-Alexandre Dumas defied all categories.

In fiction, he lives on in the characters inspired by his life. In history, he endures as a model of courage, defiance, and potential. In memory, he remains one of the most remarkable products of the Age of Revolution, proof that greatness can spring from anywhere and that the truth, however long it is silenced, cannot be denied forever.