Top 10 Sparks That Caused the American Revolution

The mid-1700s witnessed the boiling anger of the American Colonies over their British rule…. but what set off the American Revolution? From a mix of disputes and unfulfilled needs, the storm of rebellion rose, changing history.

The revolution did not happen suddenly; it was a confluence of wrongdoings, disappointments, and high hopes that spiraled into a thirst for change and independence. The key motive that sparked this revolutionary spirit was the American colonists’ feeling of wretched British rule. The British imposed restraints on colonial life without regarding the American colonists’ wants and rights.

The most significant grudge against British rule was its iron fist in the colonies, often leading to strained ties through several acts and impositions. A tight grip on taxation and trade legislation led to growing resentment among the colonists, who had no voice in the government. The people of the thirteen colonies wanted a say in the decisions that mattered to them, which was repeatedly overruled by the very establishment they aspired to be a part of. Taxes without representation and trade regulations set by a distant king grew to be a flame that engulfed the Thirteen Colonies in the cause of Liberty.

Taxation Without Representation: A Seeding Ground for Colonial Discontent

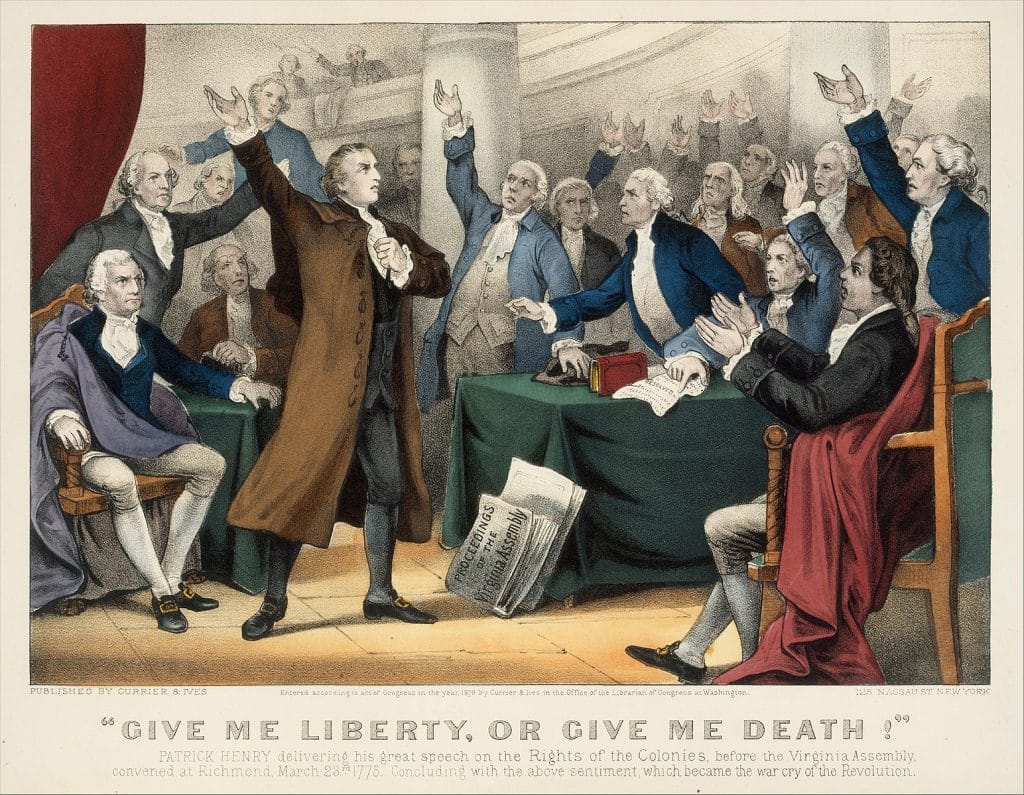

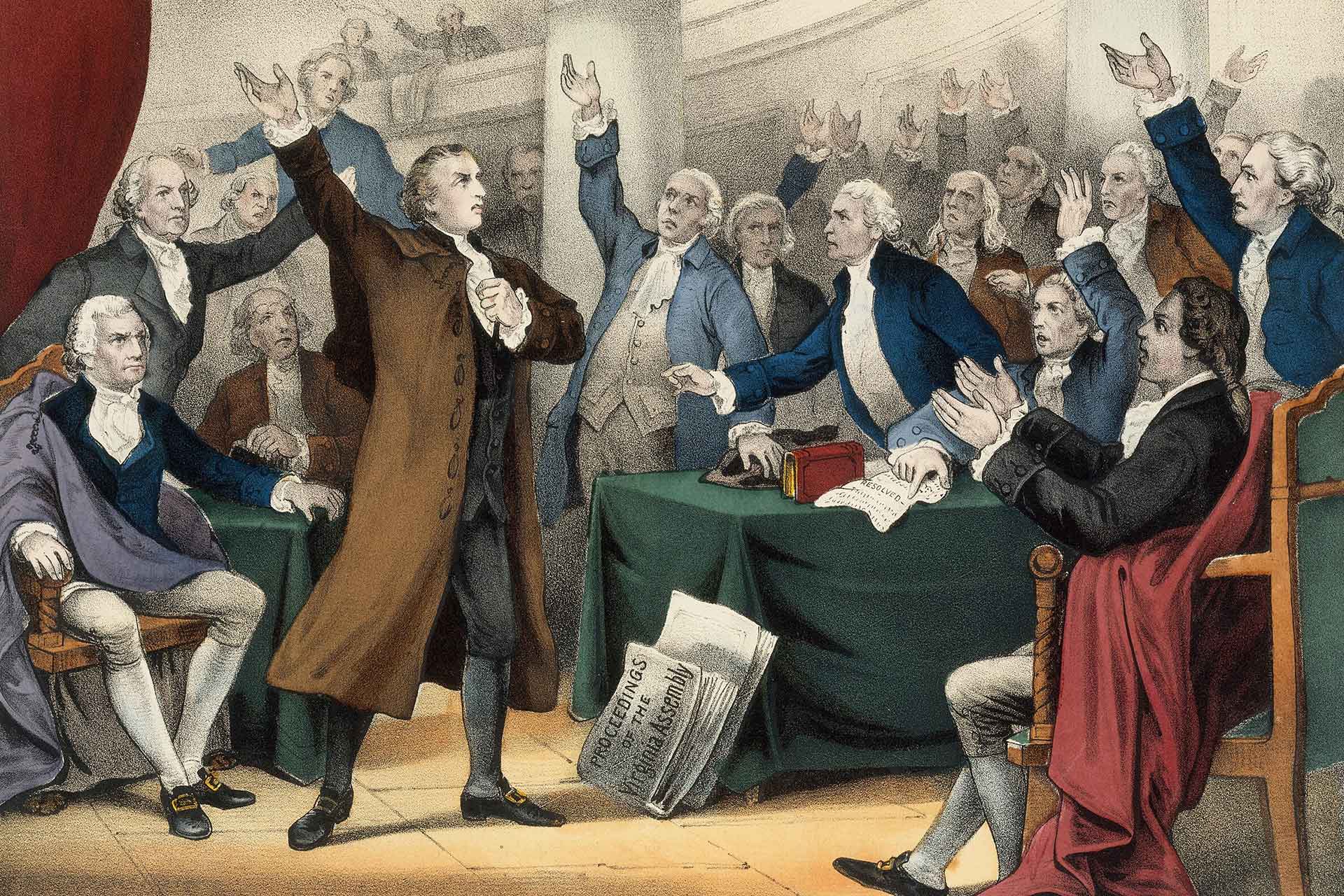

The slogan “Taxation Without Representation” came to symbolize the perceived oppression and unfairness of British rule in the eyes of the American colonists. This phrase was seen as a mighty rallying cry that encapsulated the anger and frustration of the people living in the thirteen colonies toward the distant, seemingly unresponsive British government.

The phrase was not merely a catchy slogan but encapsulated a significant political and philosophical argument that the American colonists used against the British crown. At its heart, the idea held that it was unjust for the British Parliament to impose taxes on the colonists without their consent, since the colonists had no direct representation in the British government. This absence of representation in the decision-making process was seen as a glaring flaw in the colonial relationship with the British crown.

The concept of taxation without representation was not simply a matter of financial burden on the colonists; it was fundamentally about political rights and the principles of self-governance. The colonists were increasingly alienated by British policies that seemed to disregard their needs and aspirations. The taxes, which were often levied to pay for Britain’s debts from various wars and to fund its military presence in the colonies, were seen as symbols of this larger issue of disenfranchisement.

As the rallying cry “Taxation Without Representation” gained momentum, it began to unite colonists across regions and backgrounds. The sense of injustice and the shared experience of being taxed without having a say in their government brought people together, fostering a collective identity among the colonists that transcended their local affiliations. This growing unity was a critical factor in the development of a cohesive movement capable of challenging British authority.

The problem of taxation without representation did not exist in isolation; it was part of a broader set of grievances that the colonists had with British rule. However, its power lay in its ability to crystallize these various issues into a single, comprehensible, and emotionally resonant message. This rallying cry helped galvanize public opinion, creating a groundswell of support for independence from Britain.

It was a clear, understandable, and emotionally charged issue that unified the colonists against a common adversary, setting the stage for the revolutionary movement that would eventually lead to the establishment of an independent United States.

Economic Grievances: The Mercantile Shackles on Colonial Prosperity

Mercantilist policies were seen as a brake on the developing colonial economy. The policies, which sprang from mercantilism, were developed to ensure that the new colonies would not gain economic independence.

Mercantilism’s goal of keeping a positive trade balance with its colonies and funneling the raw materials back to the mother country had the side effects of suppressing the colony’s ability to prosper and trade with others as it grew. The policies were particularly galling, as the economic success of the British far outpaced that of the colonies, a fact that only fueled resentment as the mercantilist policies did not ease as the colonies matured and grew. It’s no surprise, then, that when the desire to break free of British rule took root, a substantial economic grievance was a part of the mix of reasons to leave.

Economic liberty was limited in the mercantilist system, with colonies being forced to trade with Britain and British traders often on unfavorable terms for the colonies. This policy was a vice on the colonies, limiting trade to Britain and its other colonies. There was much resentment of this lack of freedom to trade with others, especially the other European powers and their colonies, which would have been more natural trading partners. Mercantilist policies offered little economic opportunity for the colonies outside this control. As time passed, the increasing economic prosperity of Britain while the colonies were under mercantilist control was held up as a clear example of the exploitation.

There is no question that Britain was getting richer while the colonies’ economies were on a shorter leash. The policies, which kept a tight control on the colonies’ trade, were a constant reminder to the colonists that Britain had firm control over their lives. The ever-tightening restrictions in Britain only further inflamed an already resentful and hungry populace, as they saw their economic opportunities denied. That animosity is one of the long-time forces that led to the American Revolution, as economic freedom and opportunity were key in the ideological war for independence.

Economic resentment was one part of the large ideological construct of the American Revolution. Grievances against mercantilism were but one of many parts of the whole. It is safe to say that without the drumbeat of complaints from the merchants and traders in the colonies, the path to revolution would have been slower and more arduous.

The Stamp Act and the Onslaught of Taxation Acts: The Monetary Discord that Caused the American Revolution

The period following the French and Indian War, also known as the Seven Years’ War, was marked by an economic crisis in Great Britain. The war, fought from 1754 to 1763, had drained the British treasury, and the British Parliament was desperate to find a way to pay off the massive debt that it had accumulated during the conflict.

With this in mind, Parliament turned its attention to the North American colonies, which had significantly benefited from British military support and protection. The first central taxation act, known as the Stamp Act, was passed in 1765. This law required colonists to purchase a special stamp for all official documents and legal papers, such as land deeds, wills, and even business contracts. Many colonists saw this act as an unjustified intrusion into their affairs, sparking a wave of protests across the colonies.

This was just the beginning of a long line of taxation acts that would inflame colonial tensions with Britain. In response to the Stamp Act, Parliament passed the Townshend Acts in 1767, which imposed taxes on a variety of goods, including glass, lead, paint, paper, and tea. This new tax, seen by many colonists as an attempt to control and exploit their economy, sparked outrage and resentment throughout the colonies. The British response to colonial protests only further inflamed tensions, and many colonists began to feel they were being treated as second-class citizens.

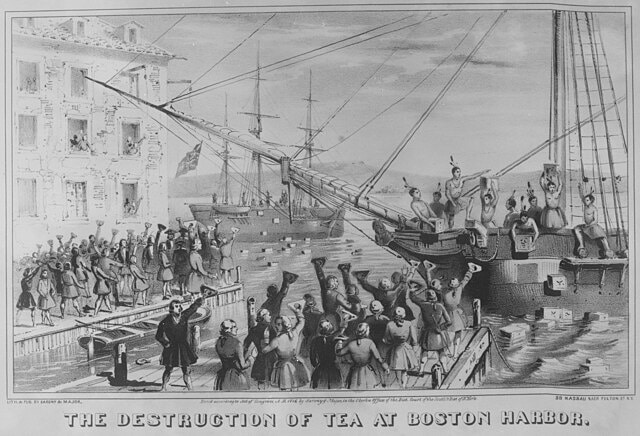

The final straw came in 1773, when Parliament passed the Tea Act. This act essentially gave the British East India Company a monopoly on the importation and sale of tea in the colonies, sparking widespread protests and the famous Boston Tea Party. This event, in which colonists dumped a shipment of tea into the harbor in protest, was a turning point in colonial relations with Britain, and it marked the beginning of the end of British rule in the colonies.

In conclusion, the British Parliament’s response to the economic crisis following the French and Indian War was to pass a series of taxation acts that ultimately inflamed tensions with the American colonies and led to the Revolutionary War. The first of these acts, the Stamp Act, required colonists to purchase a special stamp for all official documents and legal papers. This was followed by the Townshend Acts in 1767, which imposed taxes on a variety of goods, and the Tea Act in 1773, which gave the British East India Company a monopoly on the importation and sale of tea in the colonies.

These acts further inflamed colonial tensions and resentment towards British rule, and they played a major role in the events leading up to the American Revolution.

From Bloodshed To Tea: The Boston Chronicles Stirring The Winds Of Revolution

The road to the American Revolution is paved with many historical events and acts of resistance against British policies in the colonies; among the most infamous are the Boston Massacre and the Boston Tea Party. Hosted in one of the most central cities of Revolutionary America, Boston, these two major events are connected by a similar goal of public support from the colonists to oppose unfair British policies and taxation, as well as a degree of actual violence in both.

In 1770, an incident on a cold March night gave the colonists a visual image of bloodshed between the Boston people and British soldiers. A scuffle turned into a violent massacre that killed five colonial civilians. The opposing colonies utilized the Boston Massacre as a mouthpiece to inform public opinion in Boston about the illegitimate British military presence in their cities and as a popular source of agitation.

Years after the echoes of the Boston Massacre gunfire had rung out from the Boston city streets, another event at Boston’s shores was about to take place, which would have become as crucial in the history of the American Revolution as its preceding act. The 1773 Boston Tea Party was a symbolic act of destruction of tea at the dock in the harbor of Boston in response to the Tea Act imposed by Britain. The act imposed a tax on tea without colonial representation and also favored the British East India Company’s trade monopoly, which was not at all welcome to merchants and tea smugglers.

On a cold December night, the colonists dressed as Mohawk Indians and boarded three British ships, throwing 342 chests of tea into the harbor. This was an act of protest against the tyrannical tax, which the colonists could not publicly oppose but did so indirectly, yet more expressively by burning the tea, as if it were an object of hatred. It had a significant effect on the other 12 British colonies.

Not unlike the 1770 events in Boston, in the late 1770s, Boston was yet to inform and enforce public support to stand against British rulers and their extremely intolerable ways of torturing the American colonies without them having the right to speak up. Although there was a negative response from Britain at the beginning, the acts the British government forced the colonies to agree to during the events were far from considerate of colonial rights.

The 1770 Boston Massacre and the 1773 Boston Tea Party were significant events in the development of American Revolutionary ideas and feelings towards Britain and the establishment of the first unbreakable act of disobedience by the Boston colonists. They became similar in their emotional content of violence and bloodshed, and the common desire to speak up against the tyranny of the British crown.

Both acts also had a prominent effect on the other British colonies. The strong official response by Britain at first gave way to an even stronger, shared understanding that something needed to be done against the empire, and that more such bloody events or unprovoked violence by the authorities in the name of the British crown could occur.

Boston stories spread throughout the 13 British colonies at the time in the form of songs and tales about British inhumanity toward colonists’ basic needs for fair representation and taxation. A call for help to their fellow Americans and an initiation of a fight against injustice and inequality are at the core of these events. The high toll of human lives of the colonists during the events and the audacity of a British ship being burned by local American rebels were a hard-hitting last call to arms by the angry colonists in support of the American Revolution.

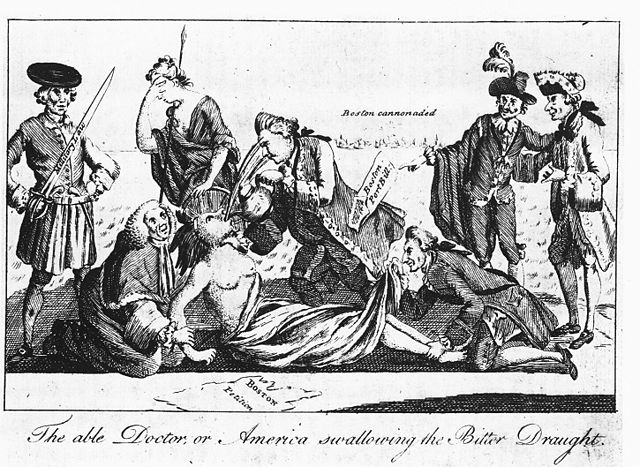

Prime Minister Lord North, author of the Boston Port Bill, forces the ”Intolerable Acts,” or tea, down the throat of America, a vulnerable Indian woman whose arms are restrained by Lord Chief Justice Mansfield, while Lord Sandwich, a notorious womanizer, pins down her feet and peers up her skirt. Behind them, Mother Britannia weeps helplessly. This British cartoon was quickly copied and distributed by Paul Revere / 1 May 1774 / Public Domain via Wiki

The Iron Fist Tightens: The Intolerable Acts of 1774

The Intolerable Acts were a series of punitive laws passed by the British Parliament in 1774. Enacted in response to the Boston Tea Party, which took place the previous year, these laws targeted the colony of Massachusetts, considered the epicenter of rebellious activity in the American colonies. The Intolerable Acts were intended to reassert British authority over the American colonies, and were seen by the colonists as an attempt to quash their growing sense of self-governance and independence.

The Intolerable Acts, which were also known as the Coercive Acts, were seen as particularly harsh and oppressive. They included the closing of the port of Boston, the revocation of Massachusetts’ charter, and the quartering of British troops in American homes. The severity of the Intolerable Acts fueled growing resentment and anger among American colonists, who saw the British government as increasingly tyrannical and oppressive.

They had a profound impact on the American colonies and were seen as a direct assault on their rights and freedoms. In particular, the closure of the port of Boston had a devastating economic impact on the city and its inhabitants, and the revocation of Massachusetts’ charter was seen as a direct attack on its right to self-governance. The acts also galvanized opposition to British rule. They led to the formation of the First Continental Congress, which brought together representatives from the various colonies to coordinate their resistance to British authority.

In response to the Intolerable Acts, the American colonies began organizing and mobilizing against British rule. The acts had a unifying effect on the colonists, who saw the British government as increasingly oppressive and tyrannical. The First Continental Congress was a major development in this regard, and the organization of colonial militias and boycotts of British goods were also important steps in the move toward rebellion.

The Intolerable Acts ultimately played a significant role in the lead-up to the American Revolution, as they helped to galvanize opposition to British rule and inspired the colonists to take action in defense of their rights and freedoms. The acts are considered to be one of the key factors that led to the outbreak of the American Revolution, and their impact on the American colonies was significant and long-lasting.

Enlightenment Ideals: A Philosophical Prelude to Revolution

Enlightenment, an intellectual movement that originated in Europe in the 18th century, had profoundly infiltrated the colonies. The progressive ideas, such as those of John Locke, gained favor among the American people. Locke’s theories on the inalienable rights of man and the social contract provided the grounds for shaping the colonial discontent. The philosophic disagreements over the subject had become apparent, and the seeds of revolution were sown, not to say germinated, by the advancing movements.

The antithesis between the Enlightenment and the British monarchy could not be more substantial. On the one hand, there was Locke’s social contract, stating that there was a harmony to be made between the sovereign and the subjects. If the balance was somehow violated, the population was free to pursue revolution. On the other hand, the British monarchy opposed such ideas of liberation and progress. Consequently, an intellectual conflict that was in absolute antithesis to British policies was created through the deliberate exchange of ideas through pamphlets, books, and conversations, and this public sphere of intellectual discourse against the current British monarchy became robust.

Ideological differences between the British monarchists and those favoring the movement of the Enlightenment could not help but become apparent through subsequent policy decisions made by the King and the Parliament, widening the distance between the people of the American colonies and Britain. In one way, British policies were fostering a stronger colonial identity in harmony with Enlightenment ideas, encouraging liberty, democracy, and individualism. In another way, the Enlightenment provided the ideas that were categorically to revolt against the ruling powers. Therefore, the American Revolution can be seen as an orchestrated reaction to British policies.

The Enlightenment largely reshaped colonial identity, and as a result, the American colonies of Great Britain developed a philosophical predisposition towards war with the British government, which eventually led to the American Revolution. Enlightenment ideas, once adopted and further evolved by the American colonists, not only implied disagreement with the British monarchy but also an ideological and intellectually justifiable path towards independence.

Colonial Self-Government and Identity: Nurturing the Seeds of Rebellion

The development of colonial self-governance was a gradual process. Over the years of relative autonomy, the colonies had begun to develop their own systems of local governance responsive to their unique economic, social, and political conditions. Additionally, this development of colonial self-governance was largely organic, evolving in response to colonists’ needs.

The colonial self-governance mentality not only developed, but it also became an important part of the identity of many colonists. The British monarchy had its own imperialistic goals, however, which involved tightening its grip on the colonies. This growing sentiment of self-governance and developing identity was in direct contrast with the monarchy’s own expansionist plans, and this was the antagonistic ideological basis of the American Revolution.

The development of a colonial identity was an evolutionary ethos that fostered a common sense of autonomy among the American colonies. Colonial local governments were also largely organic and had evolved to be responsive to the local needs of the American colonies. As the British monarchy worked to increase its own power and control over the colonies, passing unpopular and unresponsive laws and taxes, the growing divide between the colonies and the monarchy became increasingly evident. The colonies, now united by a sense of self-governance and common identity, resisted the British, and this unified sentiment was a force in the American Revolution.

The ideological evolution of colonial self-governance and a strong sense of identity were major contributing factors to the American Revolution. The colonists were not simply fighting against British taxes and unfair laws; they were fighting to preserve their own self-government and unique identity, developed over years of relative independence. This effort to fight British resistance and authoritarianism led to the unification of colonial resistance, which would eventually reach the tipping point of revolution.

Failure of Diplomatic Solutions: The Untrodden Path to Rebellion

In the turbulent atmosphere of conflict and unrest in the American colonies, there was also a growing demand for diplomacy. The colonial population, indignant at the injustices of the British government, did not by any means reject a negotiated peace. At various times, various diplomatic steps were taken to try to resolve the differences and restore calm. However, the British authorities’ stubbornness and unwillingness to accept the grievances of the American people seriously led to the total failure of diplomacy. This failure, in turn, became one of the causes of the American Revolution.

The failure of the colonists’ diplomatic efforts not only reflects the stubbornness of the British authorities but also the growing awareness of the American people. The failed diplomatic efforts forced the population to consider ways to protect their rights and freedoms.

With each failure, they became more aware of their mistakes, more determined to fight, and more steadfast in their belief in the possibility of achieving a separate state. The gap between the British and the colonies widened significantly. The former’s attempts to increase their control and interfere in the internal affairs of the colonies caused surprise and indignation. In turn, the negotiation failures clearly demonstrated to the British and the world the entire depth of this gap.

The world in the 18th century could not help but pay attention to the developing conflict between the United States and Great Britain. Diplomatic failures of the colonial authorities reflected the British determination to increase their power further, while the colonists’ desire for a peaceful settlement demonstrated their right to a better, more just system of government. Thus, the world, witnessing the colonies’ unsuccessful efforts to reach an agreement with the British authorities, already had an understanding of the situation and the people.

The history of negotiation failures shows that both sides in the conflict have primarily played their role. The former’s refusal to consider colonial grievances, desires, and needs has only demonstrated their total tyranny and barbarism. The latter, in turn, has shown it is ready to fight to the end for justice and freedom. Diplomacy has failed, leaving room for more radical methods of solving the conflict. The curtain went up on the stage of revolution, while the American colonies, for various reasons, did not even try to sit at the negotiating table, took up arms, and prepared for the upcoming great battle.

Propagation of Revolutionary Ideals: The Pen That Fanned the Flames

The propagation of revolutionary ideals was a strategic tactic to influence people and advance the cause of independence. Therefore, this dissemination should be considered as one of the factors that contributed to the commencement of the American Revolution. Colonial independence did not happen overnight, and for the rebellion to occur, public support from the inhabitants was necessary. The circulation of these ideas about the pursuit of freedom, developed by philosophers, served as one of the means to prepare people for the revolution.

It is essential to consider the work of influential thinkers as having a direct influence on the start of the American Revolution. Thomas Paine, a philosopher and journalist, played a significant role in propagating revolutionary ideas, as his articles addressed and supported the goal of independence from the British crown. He expressed his political ideas in “Common Sense,” which was published in 1776. It revealed how unreasonable the existing colonial power was and the need for a government for self-administration.

The revolutionary pamphlet appeared at the right time and was quickly read by Americans. Moreover, it was the first document that challenged British authority and was quite accessible to most readers. The pamphlet initiated a shift in perception, persuading citizens to participate in the armed conflict against the colonial power. Although this publication increased people’s ability to discuss the concept of an independent state at the national level, including at public gatherings, in homes, and taverns, British authorities were well aware of the work’s content.

At the time, the power of printed propaganda was significant, and monarchs across Europe knew and feared the circulation of revolutionary theses. Therefore, the British crown could not have been ignorant of the influence of this critical pamphlet on colonial power. The publication of the revolutionary documents was one of the reasons for the start of the war for independence, contributing to the dissemination of ideas of freedom.

The purposeful dissemination of revolutionary ideas from the American Revolution to the Revolutionary War contributed to its outbreak. It had been a gradual process that shaped people’s desire to struggle against British power. The documents from the beginning of the 18th century to Thomas Paine’s work led to an accumulation of factors that caused the outbreak of the war. People were better prepared for such developments by the ideas of earlier philosophers, demonstrating that the battle for independence was long in the making.

The Perfect Storm that Caused the American Revolution

The convoluted mosaic of the distinct causes seamlessly converged in the unique societal fabric that spanned the 13 colonies. Economic strangulation, tax revolts, the propagation of ideas, failed diplomatic efforts, and the subsequent injustices in punishment each sparked, on its own, the fuse that would eventually lead to the American Revolution. However, their interdependence and their correlation with the theme of autonomy and self-government played a critical role in collectively fuelling the desire for independence.

In conclusion, an American historian may describe the various causes of the American Revolution as a vast canvas of uniquely sparked actions intricately entwined, leading to the commencement of an irreversible trajectory toward the Revolution. However, after carefully considering the remarkable fight for freedom by the colonists and the unified ideals that defined their quest, one may view the entire revolution as an awe-inspiring display of a fledgling nation-state taking its first steps toward sovereignty.

The American Revolution was a magnanimous illustration of how a society’s ideas are intricately, directly, and quite powerfully tied to the transformative actions it takes. The precious information we glean from historicizing the American Revolution is inarguably the timelessness of the United States’ independence’s reverberating legacy.

![[Video] Women of the American Revolution Part 2](https://historychronicler.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Screenshot-2025-04-12-at-2.54.41 PM.jpg)