Doc Holliday: The Life and Times of the Wild West’s Deadly Dentist

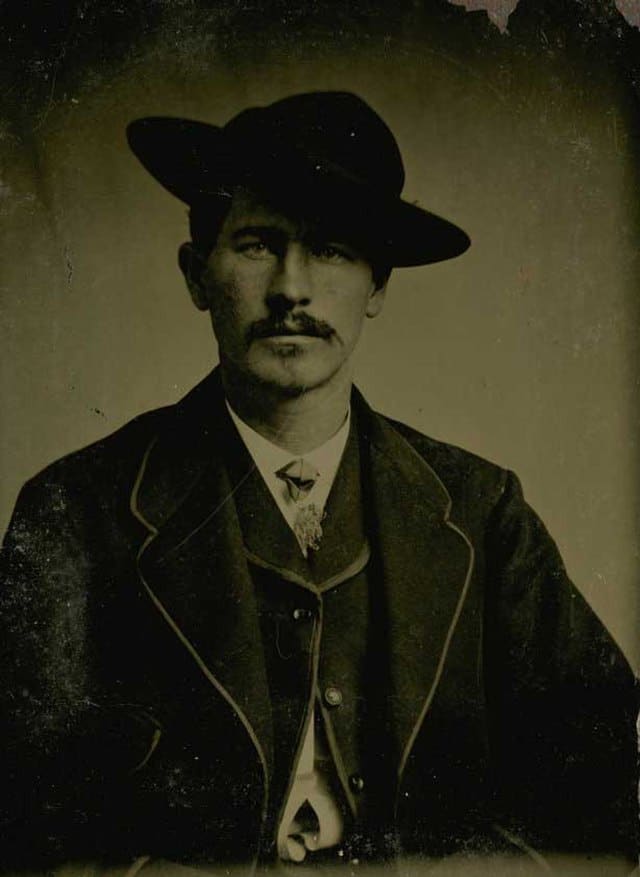

In a time where lawlessness was as rampant as the tumbleweeds that rolled across the dusty streets, emerged a figure whose reputation would be etched into the annals of American history. Dr. John Henry “Doc” Holliday wasn’t just an accomplished dentist; he was a gambler and a fearless gunfighter, a companion of the legendary Wyatt Earp in the frontier tumult of the Wild West. His life was a confluence of intelligence, deadly skill, and a relentless spirit that roared through the era like a twister, leaving a lasting imprint on the American Old West.

A graduate of the Pennsylvania College of Dental Surgery at a young age, Doc Holliday opened his dental practice in Atlanta. However, destiny’s call reverberated through the echoes of gunfire and clinking poker chips, pulling him away from a conventional life. A diagnosis of tuberculosis, the same disease that had claimed his mother, tore him from his medical profession, urging him to the dry climates of the American Southwest in hopes of better health. Yet, it was here amidst the desolate beauty and chaos of the West that Holliday found his notorious companions and, ironically, his lethal fame.

The name Doc Holliday began to resound with both dread and respect in the lawless expanses of the Wild West. His involvement in the infamous Gunfight at the O.K. Corral alongside Wyatt Earp, established him as a formidable figure of that era. His days, filled with gambles of both cards and gunfights, nights lit under the cold desert stars accompanied by the haunting cough of his ailment, crafted a legacy that mingled the melancholy of mortality with the fierce vitality of a life unyielding to its fate.

Through the veil of history, Doc Holliday emerges as a complex hero, a deadly dentist whose gun was as precise as his dental drills, whose code was as hard and unyielding as the rugged landscapes he roamed.

From Southern Gentility to the Rugged Frontier: The Early Life of Doc Holliday

Born to a respected family in Griffin, Georgia, on August 14, 1851, John Henry “Doc” Holliday was ushered into a life brimming with promise. His father, Henry Burroughs Holliday, served in the Mexican-American War and the Civil War, bearing the honor and burden of service with stoic resolve. His mother, Alice Jane Holliday, nurtured young John with a loving touch until tuberculosis snatched her away when he was just 15.

In the shadow of loss, a relentless determination took root within Holliday, driving him to excel in his studies and later propelling him into the esteemed halls of the Pennsylvania College of Dental Surgery, from which he graduated in 1872.

The mantle of a refined Southern gentleman sat well on his shoulders, yet the ghost of tuberculosis, the very ailment that claimed his mother and sister, began haunting him. The dread diagnosis became a pivot, swinging Doc’s life from the genteel streets of Georgia towards the wild, unpredictable trails of the American West.

The unforgiving disease, which had begun to claim his health, drove him from the dental offices to the gambling dens, from the salons of the sophisticated to the saloons of the desperate. As he sought the dry climates of Dallas, Texas, hoping for a respite from his ailment.

Triumph and Tribulation: Doc Holliday’s Dentistry and Duel with Destiny in Texas

In the early stages of Doc Holliday’s sojourn in Texas, he was more known for his dental prowess than his dexterity with a deck of cards or a loaded gun. Following his graduation from the Pennsylvania College of Dental Surgery, Holliday had migrated to Dallas, Texas, partnering with a family friend, Dr. John A. Seegar. Together, they pursued their dental practice with a passion and precision that soon caught the eye of the local populace and the broader professional community.

Their efforts culminated in a remarkable recognition at the Annual Fair of the North Texas Agricultural, Mechanical, and Blood Stock Association held at the Dallas County Fair. The duo clinched all three awards in the dental category: “Best set of teeth in gold”, “Best in vulcanized rubber”, and “Best set of artificial teeth and dental ware.” This triumvirate of accolades showcased the potent promise Doc Holliday harbored in the realm of dentistry.

However, fate had scripted a different narrative for Doc Holliday. The insidious onset of tuberculosis began to impede his dental practice. As coughing spells from this merciless malady frequented, often at the most inopportune of times, Holliday’s capacity to continue his dental practice dwindled. Patients grew wary, and the thriving practice he had built began to crumble.

The encroaching ailment forced Holliday to contemplate alternative avenues to earn a livelihood. It was during this dire strait that gambling metamorphosed from mere recreation to a means of sustenance for Doc Holliday. The poker tables and smoky saloons of Texas offered a refuge from the ailing reality that his health imposed.

The year 1874 marked a pivotal point in Doc Holliday’s life, pushing him further away from his original profession. On May 12th of that year, he found himself among a dozen others indicted in Dallas for illegal gambling. The law had cast a long shadow over his endeavors, and the ensuing encounter would serve as a precursor to the many legal and lethal battles that lay ahead in Holliday’s tumultuous life. The dalliance with danger escalated in January 1875 when a confrontation with a saloon keeper, Charles Austin, led to an exchange of gunfire. Though no blood was spilled in this incident, and Holliday was found not guilty, it painted a clear picture of the path that lay ahead.

The gambling incident not only fetched him a fine but also likely contributed to his decision to depart from the state of Texas. The altercation and the subsequent legal entanglement showcased the turning tide in Doc Holliday’s life, where the man of medicine was morphing into a figure of folklore in the wild, wild west. As he left Texas behind, the episodes of his life that unfolded hence were to be etched in the annals of American lore, marking a stark departure from the promising career in dentistry that once seemed his destiny.

The tale of Doc Holliday’s Texas tenure is a compelling chapter in the chronicle of a man whose life was as tempestuous as the times he lived in. From the heights of professional acclaim to the depths of legal disrepute, his story mirrors the restless spirit of the era. His transition from a dedicated dentist to a daring gambler and gunfighter is a fascinating reflection of the multifaceted, tumultuous tapestry of life in the Wild West.

Nomadic Gambler: Doc Holliday’s Journey Through Fortunes and Feuds

Leaving the Lone Star state behind, Doc Holliday embarked upon a peripatetic journey that carried him along the burgeoning frontiers of the American West. His first stop was Denver, Colorado, where he trailed along the stage routes, gambled in small towns and army outposts, and embraced the aura of anonymity that the wilderness offered. By the summer of 1875, Denver knew him as “Tom Mackey,” the faro dealer at John A. Babb’s Theatre Comique located at 357 Blake Street.

However, tranquility proved elusive. An altercation with Bud Ryan, a notorious gambler, erupted into a knife fight that left Ryan severely wounded and drove Holliday towards newer horizons. The news of gold discovery in Wyoming beckoned, and by February 5, 1876, Doc Holliday had set foot in Cheyenne.

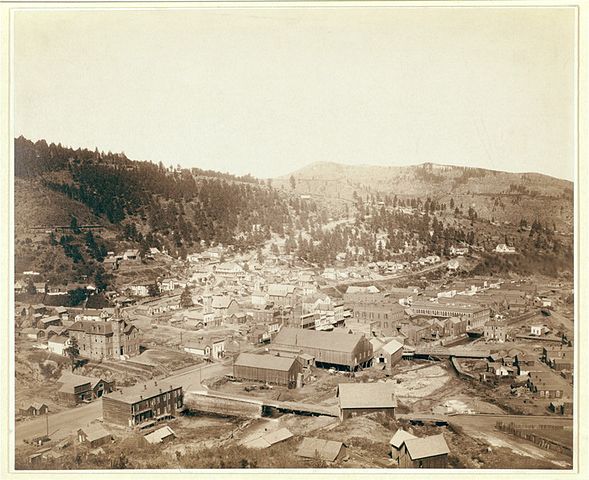

Here, he resumed his vocation as a faro dealer, this time under the employment of Thomas Miller, proprietor of the Bella Union Saloon. As autumn cast its golden hue, Miller translocated the saloon to Deadwood, South Dakota, amidst the Dakota Territory’s gold rush fever. Holliday, forever in quest of fortune’s favor, followed suit.

The year 1877 saw Doc Holliday retracing his steps back to Cheyenne, and then Denver, before venturing into Kansas to visit familial ties. His aunt provided a brief respite in his otherwise tumultuous existence. But the allure of the gambling table soon beckoned him to Breckenridge, Texas. His time there was marked by an acrimonious encounter on July 4, 1877, with gambler Henry Kahn. A disagreement spiraled into violence, with Holliday resorting to his walking stick to administer a savage beating upon Kahn. Both men faced the law’s slap on the wrist, but the episode was far from concluded.

Revenge brewed in Kahn’s heart, and later the same day, he seized the opportunity to shoot an unarmed Holliday, inflicting grievous injuries. The event was momentous enough to stir the local press into a whirlwind, with the Dallas Weekly Herald prematurely heralding the demise of Doc Holliday on July 7.

The erroneous news, however, triggered a familial rescue mission. Doc Holliday’s cousin, George Henry Holliday, journeyed westward to aid in his recovery. This period, marked by familial care, a brush with death, and the ever-loyal companionship of misfortune, exemplified the tempestuous nature of Doc Holliday’s existence. The specter of death had made its first overt pass, yet fate had more cards to play. The nomadic gambler’s tale was far from its final chapter, as the west held more fortunes and feuds, allies and adversaries, awaiting him in the murky haze of gun smoke and the echoing clamor of saloon revelries.

A Dance of Fate: The Meeting of Doc Holliday, Big Nose Kate, and Wyatt Earp in the Texan Frontier

Once the rough Texan winds blew away the storm clouds of injury and near-death from his tumultuous life, a recuperated Doc Holliday found himself drawn to the rough-and-tumble surroundings of Fort Griffin, Texas.

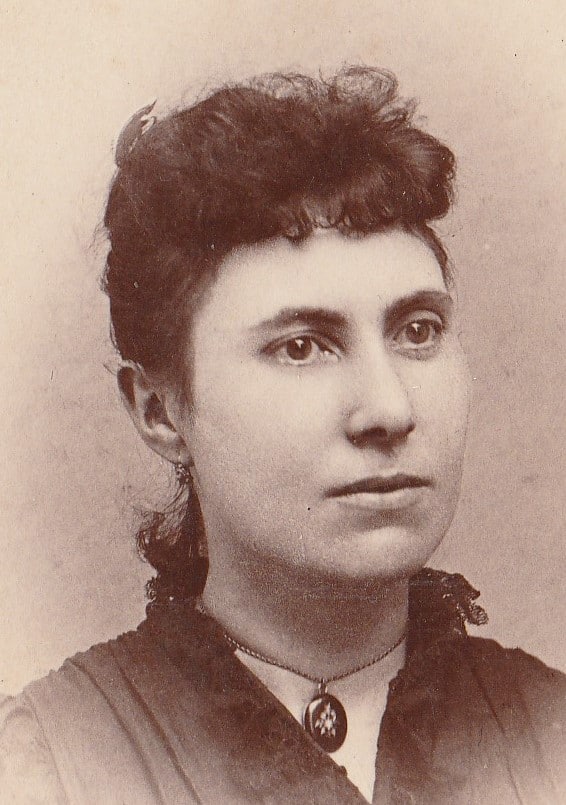

At the heart of this frontier town was John Shanssey’s saloon, where Holliday, dealing cards amidst the clinking of whiskey bottles and the boisterous revelries of patrons, crossed paths with a woman who was as tenacious as him, Mary Katharine “Big Nose Kate” Horony. Kate, a dance hall woman and at times a lady of the night, was a spirit unrestrained by the traditional norms of the time.

Though educated, she had chosen a life that offered her independence and liberation from societal expectations. In a world that was often cruel and unforgiving, she found a semblance of affinity with Doc Holliday, marking the beginning of a unique companionship. Their bond was a blend of mutual respect, camaraderie, and an understanding of the wild unpredictability that encapsulated their existences.

In the wake of October 1877, the echoes of outlaw roguery resonated through the frontier when a band led by “Dirty” Dave Rudabaugh looted a Santa Fe Railroad construction camp in Kansas. Rudabaugh’s flight south into Texas initiated a lawman’s pursuit; Wyatt Earp was deputized temporarily as a U.S. marshal and set out from Dodge City, tracing the outlaw over the sprawling distances to Fort Griffin.

Earp’s investigation led him to the buzzing hive of John Shanssey’s Bee Hive Saloon. Within the Saloon’s dimly lit confines, Shanssey hinted at Doc Holliday’s recent gambling duel with Rudabaugh. Acting on this clue, Earp consulted Holliday, who, while shuffling a deck of cards amidst the smoky milieu, pointed towards Kansas as Rudabaugh’s possible retreat. This instance marked the beginning of an acquaintance that would soon etch a deep mark on the annals of Wild West folklore.

With lawman duty calling, Earp veered back to Fort Clark and by early 1878 found himself vested as the assistant city marshal in Dodge City, under Charlie Bassett. As fate would have it, the summer of 1878 also saw Holliday and Kate arriving in Dodge City, where they lodged at Deacon Cox’s boarding house, taking on the aliases of Dr. and Mrs. John H. Holliday. Holliday, with a renewed spark, aspired to refurbish his dental practice. An advertisement in the local daily heralded the services of J. H. Holliday, Dentist, at Room No. 24 Dodge House, where unsatisfied patrons were assured a refund, a display of his undying confidence in his professional prowess.

The summer seemed to unfold in a calmer vein until a storm rode into town. Two hard-riding cowboys, Tobe Driscall and Ed Morrison, whom Earp had earlier driven out of Wichita, stormed into Dodge City alongside a menacing gang. They unleashed a wave of terror down Front Street, leading into the Long Branch Saloon where they shattered the peaceful ambiance with bullets and threats.

The ruckus alerted Earp, who stormed into the saloon only to be greeted by a barrage of hostile guns aimed at him. Unfazed, in the backdrop, Doc Holliday, with a steely gaze and a pistol aimed at Morrison’s head, orchestrated a swift disarming of the gang, thereby snatching Earp from the jaws of death.

Accounts of the event, though colored with various shades of exaggeration and dramatization over the years, unequivocally portrayed Doc Holliday’s decisive intervention as a life-saving act for Earp. Despite the murky details surrounding the encounter, this event fostered a bond of friendship and mutual respect between Doc Holliday and Wyatt Earp, a friendship that would soon intertwine their destinies in the unfolding saga of the Wild West. Their camaraderie, forged in the furnace of frontier lawlessness and gunpowder, would become the stuff of legends, narrated and celebrated in the annals of American folklore for generations to come.

The Unyielding Horizon: Doc Holliday’s Journey with the Earps to Tombstone

As the pages of 1878 slowly rustled towards its close, Doc Holliday, along with his steadfast companion, Kate Horony, ambled into the quaint township of Las Vegas, New Mexico, shortly before the cheer of Christmas filled the cold winter air. The beckoning warmth of the 22 hot springs near the town, believed to ease the iron grip of tuberculosis, might have offered some allure to the ailing dentist.

Despite the surrounding despondency of the season, Holliday reinstated his dental practice amidst the simmering hopes of card tables. However, the bitter cold of the winter was unrelenting, and the business at both the dentist’s chair and the gambling tables was sparse.

The following March brought an unanticipated frost to Holliday’s ventures as the New Mexico Territorial Legislature, in a sweeping move, outlawed gambling. Consequentially, Holliday found himself under indictment and was fined for “keeping [a] gaming table.” The relentless cold paired with the new legal restrictions on gambling, hurried Holliday and Horony back to the familiar turf of Dodge City as spring began painting the landscape.

The autumn of 1879 saw a notable diversion in the paths of Doc Holliday and Wyatt Earp. Earp, relinquishing his badge as the assistant marshal in Dodge City, set his compass towards the mystic lands of Arizona Territory, accompanied by his common-law wife Mattie Blaylock, his brother Jim, and Jim’s wife Bessie. Holliday and Horony, after a short sojourn in Dodge City, found themselves gravitating back to Las Vegas, New Mexico. Fate, as it often did in the turbulent lives of these frontier dwellers, twined their paths once again. In November, Holliday, Horony, and the Earps rendezvoused in Prescott, Arizona, amidst the mellow autumn winds.

The narrative of Holliday’s life soon enmeshed itself with the tales of the frontier once again. Amidst the burgeoning township near the tracks in Las Vegas, which the Santa Fe Railroad had brought to life, Holliday found himself embroiled in a deadly confrontation on a summer afternoon in 1879. As the dust settled, the saloon where Holliday and former lawman John Joshua Webb were seated became the focal point of tragedy.

A confrontation with a former U.S. Army scout, Mike Gordon, over a saloon girl’s affection led to lead being exchanged, ending in Gordon’s demise the subsequent day. In the wake of this event, Holliday and Webb partnered to open the “Doc Holliday’s Saloon,” a clapboard structure that stood as a testament to Holliday’s indomitable spirit amidst his turbulent journey.

The wheels of fortune spun once again when Wyatt Earp, on October 18, 1879, stepped into Holliday’s path, bearing tales of silver treasures awaiting in the far-flung town of Tombstone, Arizona Territory. The allure of prosperity and adventure coerced Doc Holliday and Horony to join the Earp caravan as it meandered through the vast stretches to Prescott, Arizona Territory. Upon their arrival, while the Earps continued their journey towards Tombstone, Holliday, intrigued by the gambling prospects, decided to linger in Prescott. He delved into the bustling gambling scene, his formidable reputation on the card tables echoing through the saloons of Prescott.

As the summer of 1880 tenderly folded into autumn, the call of camaraderie and the promise of frontier justice led Doc Holliday to the rugged terrains of Tombstone, where the Earps awaited. Arriving in September, amidst whispered tales of outlaw menace and the need for unyielding lawmen, Holliday once again found himself at the center of unfolding frontier lore.

His arrival in Tombstone wasn’t merely a geographical transition, but a herald of the tumultuous and legendary episodes that would etch the names of Doc Holliday and the Earps in the unyielding annals of the Wild West, awaiting to be narrated through the haze of time.

Turbulent Tombstone Tenures: Doc Holliday’s Early Brush with Frontier Justice

As the heat shimmered off the dusty streets of Tombstone, Doc Holliday’s stormy relationship with Kate Horony thrived amidst the rugged lawlessness of the frontier life. Their fiery confrontations were as known as the whiskey that fueled them. However, one particularly blistering row saw Horony cast out into the Tombstone night by an irate Holliday. This expulsion carried with it a ripple effect that would momentarily alter the course of Holliday’s tumultuous tenure in Tombstone. Seizing this delicate thread of discord,

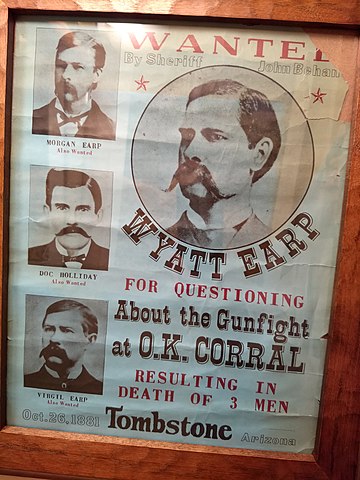

County Sheriff Johnny Behan and Milt Joyce, members of the opportunistic Ten Percent Ring, saw a chance to ensnare Doc Holliday in a web of criminal allegations. Pouring more alcohol into the already turbulent situation, they coaxed a vengeful Horony into signing an affidavit. This document, conceived in malevolent intent, accused Holliday of a grievous crime – an attempted robbery and murder on a Kinnear and Company stagecoach, laden with silver bullion, on the fateful day of March 15, 1881.

The attempted robbery of the stagecoach was not a trifling matter, with the assailants leaving behind a trail of blood and gunpowder. Bob Paul, running for the Sheriff’s seat in Pima County and working as a shotgun messenger for Wells Fargo at the time, had replaced the usual driver, Eli “Budd” Philpot due to his illness. When highwaymen accosted the stage between Tombstone and Benson, Arizona, gunfire erupted.

Paul fiercely defended the precious cargo, but not without casualties – both Philpot and passenger Peter Roerig lost their lives to the outlaw’s bullets. Among the robbers was a cowboy named Bill Leonard, a known associate of Holliday from New York. The affidavit, borne from spite and machinations, led to an arrest warrant being issued against Holliday by Judge Wells Spicer, igniting a swirl of rumors about Holliday’s involvement in the deadly hold-up.

The news of the arrest warrant greeted an already drunken Doc Holliday later that day as he staggered into Joyce’s saloon. Bitter words were exchanged, insults hurled, and demand for his firearm denied. The confrontation exploded into gunfire, with Holliday returning, a revolver in hand. In the subsequent hail of bullets, Joyce found a bullet through his palm, and his bartender, Parker, nursed a wounded toe. However, the chaos of the scene ended with Holliday being subdued by a pistol-whip from Joyce, landing him into a deeper quagmire of legal entanglements, as he found himself convicted of assault.

Amidst the rough tides of frontier justice, the Earps emerged as a beacon of hope for Holliday. They orchestrated a defense, unearthing witnesses who attested to Holliday’s absence from the scene of the stagecoach ambush. A now sober Horony, perhaps stricken with remorse or clarity, confessed to her manipulation by Behan and Joyce, exonerating Holliday from the grave accusations. Judge Spicer, seeing through the veil of deceit, released Holliday, while the district attorney dismissed the spurious charges as “ridiculous”.

The tumult ended with Doc Holliday furnishing Horony with some money and a ticket out of Tombstone. However, this episode did more than just agitate the dust of Tombstone; it added layers to the already complex relationship between Holliday and the Earps, tightening the bond of friendship and trust amidst the tempest of lawlessness that sought to engulf them. The whisperings of frontier justice were in the air, echoing the foreboding murmurs of confrontations yet to come.

The OK Corral: A Crossfire of Law and Outlaw

On the cusp of destiny, October 26, 1881 unfurled amidst an air tense with the smell of cold gunmetal in Tombstone. Virgil Earp, striding the dusty streets as both deputy U.S. marshal and the city’s police chief, had a storm brewing on his horizon. Rumors swirled through the wind of cowboys, their tempers as fiery as their threatened vendettas against the Earps and Doc Holliday, ambling around town with the cold steel of their guns against the town’s decree.

As per the ordinance, every newcomer to Tombstone was obliged to leave their firearms at a saloon or stable. Yet, these cowboys, laden with old grudges, seemed to be gearing up for confrontation. Foreseeing the clouds of trouble, Virgil Earp temporarily deputized Doc Holliday, rallying the support of his brothers Wyatt and Morgan. As preparations were underfoot, Virgil fetched a short coach gun from the Wells Fargo office, banding together with his makeshift posse to confront the defiant cowboys.

As they stepped onto the firmament of Fremont Street, a fateful encounter with Cochise County Sheriff Behan unfolded. The sheriff, either through words or implication, assured them that he had disarmed the rebellious cowboys. To maintain a semblance of calm among the townsfolk, Virgil handed the coach gun to Holliday, whose long coat would serve as a cloak of concealment. In exchange, Virgil carried Holliday’s walking stick. Their march led them to a narrow enclave on Fremont Street, nestled between Fly’s boarding house and the Harwood house. Given Holliday’s lodgings were at Fly’s, it was suspected that the cowboys might have been lying in wait to ambush him.

The confrontation that ensued is now etched in the annals of Wild West lore, its narrative often adorned with varying shades of truth depending on the teller. In the ensuing crossfire, witness accounts oscillated between versions. Some asserted that Holliday brandished his known nickel-plated pistol, while others claim the first roar of gunfire came from a longer, bronze-colored gun, perhaps the concealed coach gun. Amidst the thunder of gunfire, Tom McLaury fell, a shotgun blast tearing through his chest, courtesy of Doc Holliday.

The exchange was as swift as it was deadly; Holliday found himself grazed by a bullet, supposedly from Frank McLaury’s gun. As lore has it, a defiant Holliday faced his attacker, who shouted, “I’ve got you now!” to which Holliday retorted, “Blaze away! You’re a daisy if you have.” When the dust settled, Frank McLaury lay dead, a destiny of lead met both in his stomach and behind his ear. A secondary narrative also hints at Holliday wounding Billy Clanton amidst the chaotic skirmish.

The thorough examination of the fierce exchange presents a jigsaw of actions that point towards either Holliday or Morgan Earp as the harbingers of the fatal bullet that ended McLaury on Fremont Street. With Doc Holliday positioned to McLaury’s right and Morgan to his left, McLaury’s fatal shot to the right side of his head often attributes credit to Holliday. Yet, an earlier shot from Wyatt Earp had already met McLaury’s torso, a wound sufficient to spell demise.

Regardless of who delivered the coup de grace, the aftermath of this short-lived yet ferocious encounter reverberated through the courts. A 30-day preliminary hearing concluded the actions of the Earps and Holliday were within the bounds of their lawmen duties, yet Ike Clanton’s thirst for reprisal was far from quenched.

As the echoes of gunfire faded into the crisp Tombstone air, the legends of that day interwove into the cultural fabric of the Wild West. The gunfight at the OK Corral, despite its brevity, imprinted a tale of law, outlaw, and the fine line in between, immortalizing Doc Holliday and the Earps in a narrative retold through countless recounts and reenactments. Amidst the vast, open frontier, the OK Corral’s legend stands as a stark silhouette against the blazing Arizona sky, an epitome of the wild, unruly heart of the West that beats on in tales of courage, camaraderie, and confrontation.

The Aftermath of the OK Corral Shootout

The underbelly of Tombstone started boiling over post the dramatic OK Corral shootout. The situation exacerbated when, in December 1881, Virgil Earp was ambushed and suffered permanent injuries. Following suit, Morgan Earp met his end in a fatal ambush come March 1882. Eyewitnesses didn’t hesitate in pinning several Cowboys as the culprits behind Virgil Earp’s attack on December 27, 1881, and the fatal shooting of Morgan Earp on March 19, 1882.

More than just whispers in the wind, additional circumstantial evidence solidified the accusations. In the wake of his brother’s maiming, Wyatt Earp took up the role of deputy U.S. marshal, deputizing a squad including Doc Holliday, Warren Earp, Sherman McMaster, and “Turkey Creek” Jack Johnson.

The revenge narrative started penning its chapters when Wyatt Earp, accompanied by his deputies, escorted Virgil Earp and Allie to a train bound for Colton, California, to stay with their father whilst Virgil recovered from his shotgun wound. However, fate had scripted a detour.

On March 20, 1882, while at Tucson, they stumbled upon an armed Frank Stilwell and possibly Ike Clanton skulking among the railroad cars, seemingly with efarious intentions towards Virgil. The dawn of the following day saw Stilwell’s corpse alongside the railroad tracks, his body telling tales of buckshot and bullets. Later in life, Wyatt openly stated that he filled Stilwell with lead from his shotgun.

In reaction, Tucson Justice of the Peace Charles Meyer set forth arrest warrants for five members of the Earp party, Holliday included. They made a brief return to Tombstone on March 21, where Texas Jack Vermillion, among possibly others, joined their ranks. The next morning led the part of the Earp faction to Pete Spence’s ranch, trailing further to a wood-cutting camp.

Eyewitness Theodore Judah recounts the Earp group arriving around 11 a.m., enquiring about Spence and Florentino “Indian Charlie” Cruz. Discovering Spence in jail, they tracked down Cruz nearby, ensuing in a gunshot melodrama that ended with Cruz’s lifeless body riddled with bullets the next morning.

Gunfight at Iron Springs

The script of revenge trailed to Iron Springs in the Whetstone Mountains on March 24, where Earp’s posse planned to rendezvous with Charlie Smith, who was to bring $1,000 from their supporters in Tombstone. A reconnaissance led by Wyatt and Doc Holliday unraveled a group of eight cowboys camping by the springs. The face-off was inevitable. Curly Bill, recognizing Wyatt, took the first shot, which acted as a cue for the rest of the cowboys to draw their weapons. A hailstorm of bullets ensued with Wyatt dismounting, clutching his shotgun. “Texas Jack” Vermillion’s horse became an unintended casualty, falling and pinning him down, his rifle wedged underneath. Lacking cover, Holliday, Johnson, and McMaster beat a strategic retreat.

Wyatt avenged the shotgun fire from Curly Bill, his shotgun roar silencing Bill with a chest shot that nearly halved him, as per Wyatt’s account. Bill’s corpse found its resting place by the spring’s edge. The cowboys retaliated with a spray of bullets, with Vermillion’s horse being the sole casualty. Wyatt, clutching his pistol, managed to lodge a bullet in Johnny Barnes’ chest and another in Milt Hicks’ arm.

Vermillion’s desperate attempt to retrieve his rifle exposed him to the Cowboys’ rain of bullets, yet Holliday shielded him, helping him find cover. Wyatt’s efforts to remount were hindered as his cartridge belt had descended around his legs. Amidst the gunfight, bullets played with Wyatt’s long coat, boot heel, and even kissed the saddle horn, each narrowly missing him. With immense effort, Wyatt finally remounted, retreating with McMaster who too had a close call with a bullet.

Death of Johnny Ringo

The saga of vengeance seemingly transcended to a new chapter with the mysterious demise of Johnny Ringo on July 14, 1882. His body was discovered in West Turkey Creek Valley near Chiricahua Peak, Arizona Territory, with a bullet hole in his right temple, a revolver hanging from his finger.

While the coroner declared it a suicide, whispers of another narrative had begun. Glenn Boyer’s book “I Married Wyatt Earp” stirred the pot, suggesting that Wyatt and Holliday had taken a detour to Arizona in early July, finding Ringo in the valley, ending his life. Despite the controversy surrounding Boyer’s book, the narrative found its way into popular culture, notably being depicted in the film “Tombstone”, portraying Holliday as Ringo’s executor.

However, evidence surrounding Doc Holliday’s exact whereabouts during Ringo’s death remains foggy at best. Court records from Pueblo County, Colorado, mention Holliday and his attorney appearing in court on July 11 and again on July 14 for “larceny” charges.

However, a writ of capias on the 11th hints at Holliday’s possible absence from court. Further, Holliday was spotted in Salida, Colorado on July 7, a good 550 miles away from the site of Ringo’s corpse, and in Leadville on July 18. Karen Holliday Tanner, a biographer, mentions an outstanding murder warrant against Holliday in Arizona, making it quite improbable for him to venture into Arizona at that point.

The narrative, veiled with the heavy drapes of mystery, conjecture, and scarce reliable documentation, continues to incite curiosity, as does the character of Doc Holliday, whose life was anything but a calm stroll through the valleys of Georgia.

The Unyielding March of Justice: Holliday’s Struggles Post Arizona

Following the turbulent trails in Arizona, Doc Holliday and four of his compatriots, laden with the warrants for Frank Stilwell’s death, knew it was time to bid the desert land adieu. Their eyes were set towards the relatively peaceful landscapes of the New Mexico Territory, with Colorado being the final stop. Among the rugged posse, the steadfast camaraderie between Wyatt Earp and Holliday hit a rough patch leading to a grievous parting of ways in Albuquerque. Their guns, which once roared in unison against the foes, were now holster-bound by disagreements, as their pathways forked under the New Mexican sun.

Arriving in Colorado seemed like a new chapter, yet the echoes of past deeds followed. On May 15, 1882, Doc Holliday’s freedom was curtailed by the shackles of law in Denver, arrested on the warrant from Tucson regarding Stilwell’s demise. This news echoed through the plains reaching the ears of Wyatt Earp who now feared for Holliday’s fate in an Arizona courtroom. Eager to help, Earp reached out to Bat Masterson, a staunch ally and then the chief of police of Trinidad, Colorado. Masterson, heeding to the desperate call, fabricated bunco charges against Holliday in a crafty move to keep him away from Arizona’s harsh judicial claws.

The machinations of justice rolled on, setting Doc Holliday’s extradition hearing on the cusp of May’s end. However, the eve before the hearing saw Masterson, draped in desperation and hope, seeking a late-night audience with Colorado Governor Frederick Walker Pitkin. With E.D. Cowen, the capital reporter for the Denver Tribune, wielding political influence, Masterson presented the folly within the extradition papers and an existing Colorado warrant against Holliday. Through the veil of night, the plea reached Governor Pitkin, who, persuaded by the legal misgivings and Masterson’s earnest plea, decided to refuse Arizona’s request for extradition.

Masterson, with a breath of relief, escorted Doc Holliday to Pueblo, ensuring his release on bond a fortnight post his arrest. The sun of June 1882 saw the reunion of Wyatt and Holliday in Gunnison, after Wyatt’s relentless efforts played a crucial role in preventing Holliday’s conviction concerning Frank Stilwell’s murder charges. However, the spectre of lawlessness continued to shadow Holliday.

In 1884, the quaint town of Leadville, Colorado, witnessed Holliday’s last known confrontation in the murky halls of Hyman’s saloon. The circumstances were dismal; Holliday, once a feared gambler, was now whittling down to his last dollar. The narrative unfolded with a loan of $5 from William J. “Billy” Allen, a sum equivalent to a modest sum today, but significant in the rugged economic landscape of the wild west. As debts remained unpaid and threats loomed, Holliday’s fears manifested into a dangerous plan to confront Allen at Hyman’s, where eventually gunshots echoed, marking another dark chapter in Holliday’s turbulent life.

Following the Leadville shooting, Doc Holliday once again found himself before the court, with the tenuous claim of self-defense standing between him and the gallows. Though acquitted on March 28, 1885, the face of the deadly dentist reflected the wear of time and turmoil. His remaining days in Colorado were a battle against not just the law but a harsher judge – his deteriorating health. The high altitudes of Leadville proved unsparing to Holliday’s frail frame, already ravaged by tuberculosis. As his days trickled down amidst alcohol fumes and laudanum vapours, so did the tales of his gambling prowess, leaving behind a legacy intertwined with both the gavel and the gun in the annals of the wild west.

Fading Embers: Doc Holliday’s Final Draw

The sunset years of Doc Holliday’s tumultuous journey began to dim following his acquittal from the Leadville shooting trial. The ill-fated yet resolute figure of the wild west carried with him a legacy that swung between the realms of dread and reverence, evoking tales that would meander through the sands of time. The tumult and gunfire that once punctuated his life were slowly giving way to a quiet, albeit persistent, confrontation with mortality.

As a chilling frost draped the late winter of 1886, the Windsor Hotel in Denver cradled a poignant reunion between Holliday and his steadfast companion, Wyatt Earp. The encounter was immortalized in the words of Sadie Marcus, as she recounted a skeletal Holliday, propped on unsteady legs, his relentless cough a haunting melody to the tales of their shared past. Their farewell echoed the melancholy that time often weaves around camaraderie, marking a somber yet memorable chapter in the annals of their kinship.

The year 1887 saw a prematurely gray and haggard Doc Holliday, weaving through the tapestry of his ailments towards the hopeful respite of Hotel Glenwood, located near the warm embrace of Glenwood Springs, Colorado. Nestled amid the promise of healing waters, Holliday sought to tame the relentless tuberculosis that now held him in a vice grip. However, the sulfurous whispers from the springs seemed to gnaw at his already frail constitution, possibly exacerbating his affliction rather than alleviating it.

On the morning of November 8, 1887, as death beckoned, a tinge of humor colored Doc Holliday’s final moments. His request for a shot of whiskey was met with denial, prompting a glance towards his bootless feet followed by a quirk, “This is funny.” Doc had always envisioned a death amidst gunfire, with boots on; however, fate had scripted a different tale. His passing remained veiled from Wyatt Earp until months later, whilst Kate Horony claimed a tender vigil by his side during those concluding hours, a claim resonated by several sources of the time.

Within the labyrinth of tales surrounding Holliday’s life, his persona, fiercely enshrined within the gambler’s guise, was both a veil and a sword. His expertise in both gunfights and gambling was a duality that carved respect and fear alike on the visage of those who crossed his path. Noteworthy was Holliday’s encounter with Johnny Ringo, wherein the quick-draw confrontation was thwarted by timely interference by Tombstone law enforcement.

His involvement in the infamous Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, and the subsequent Earp Vendetta Ride, showcased his ruthless efficiency with firearms—a dance with death that Holliday remarkably excelled at, despite the vicious grasp of tuberculosis. A recounting of his adventures by Holliday noted numerous arrests, attempted hangings, and ambushes, an odyssey that seemed as relentless as the tuberculosis that plagued him.

Despite his reputation, the annals of time and law only whisper of a handful of men meeting their fate at Holliday’s hands. The folklore enveloping his figure often embroidered many a tale, which Holliday neither confirmed nor refuted, perhaps finding the notoriety useful. It was a double-edged sword that brought both fear and respect to his name in the turbulent theaters of the wild west. Through the words of Virgil Earp in a conversation with the Arizona Daily Star, the enigmatic nature of Doc Holliday shone through.

“There was something very peculiar about Doc Holliday. He was gentlemanly, a good dentist, a friendly man, and yet outside of us boys I don’t think he had a friend in the Territory. Tales were told that he had murdered men in different parts of the country; that he had robbed and committed all manner of crimes, and yet when persons were asked how they knew it, they could only admit that it was hearsay and that nothing of the kind could really be traced up to Doc’s account.”

Virgil Earp – March 1882 interview with the Arizona Daily Star

An epitome of dichotomies, Doc Holliday’s legend was that of a gentleman, a skilled dentist, a formidable gambler, a deadly gunfighter, and above all, a resilient character who left an indelible imprint on the tapestry of the wild west, much akin to the lingering smoke of his Colt’s barrels against the crimson horizon.

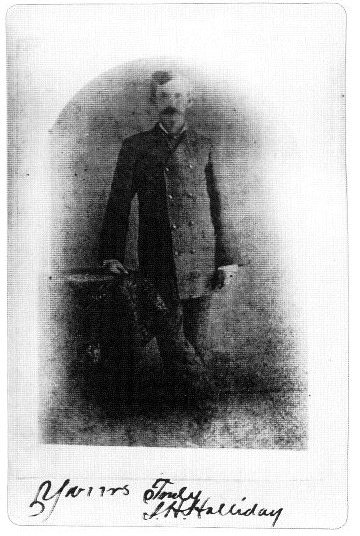

Featured Image Attribution: tifoultoute, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons