Tupac Amaru II: The Last Stand of Incan Resistance against Spanish Rule

Túpac Amaru II, born José Gabriel Condorcanqui, is best remembered for the massive indigenous uprising against Spanish colonial rule that he led in the late 18th century. But before he became the symbol of resistance and rebellion, there’s much to know about his life and lineage.

Tupac Amaru’s Early Life & Lineage

José Gabriel Condorcanqui was born in 1738 in Surimana, a region in the highlands of present-day Peru. He belonged to the upper class of indigenous society, known as the “kurakas.” These were local leaders or chieftains who acted as intermediaries between the Spanish colonial authorities and the native population. The kurakas played a vital role in the colonial system, ensuring the collection of tribute from the indigenous people and overseeing the forced labor system, the ‘mita’.

Crucially, Condorcanqui claimed direct descent from the last rulers of the Inca Empire. He was believed to be a descendant of Túpac Amaru I, the last Inca leader who was executed by the Spanish in 1572. This lineage was more than just symbolic; it was a source of authority and respect among the indigenous population. José Gabriel would later adopt the name Tupac Amaru II, drawing on the power of this lineage and the memories of the Inca Empire’s last days.

Túpac Amaru II lived a relatively conventional life for a man of his status. He was educated, could speak both Quechua (the language of the Incas) and Spanish fluently, and was married with children. His position allowed him to travel frequently, interact with both Spanish officials and indigenous communities, and witness firsthand the abuses of colonial rule. These experiences, combined with his lineage, laid the foundation for his leadership in the rebellion against the Spanish.

Peruvian Politics, Economy, and the Hardship of the Indigenous People

The late 18th century in South America, particularly in the region which is today Peru, was marked by a complex interplay of economic distress, political discontent, and deep-seated local resentments. These multifaceted tensions created the kindling for Tupac Amaru’s rebellion, one of the most significant indigenous uprisings against Spanish colonial rule.

Economically, Spanish colonialism had imposed a heavy burden on the indigenous population and mestizos alike. The repartimiento system, a form of labor draft, forced native communities to supply workers for mines and other colonial enterprises. While this system was officially abolished in the mid-18th century, it was replaced by economic policies that continued to exploit indigenous labor. The Bourbon Reforms, aimed at increasing colonial revenue for the crown, resulted in higher taxes and stricter controls over the indigenous and mestizo populace. These taxes disproportionately affected the lower classes, creating widespread economic hardship.

Politically, the Bourbon Reforms sought to consolidate power and reduce the influence of Creole elites, leading to increased dissatisfaction among the local leadership. The crown’s attempt to centralize authority, combined with the marginalization of Creoles in administrative positions, fostered resentment and a sense of alienation. This centralization of power often manifested in policies that were out of touch with the realities and complexities of local life, further widening the chasm between rulers and the ruled.

At a local level, cultural and racial tensions exacerbated the situation. Spanish officials and Creoles frequently looked down upon indigenous culture, and the forced labor systems maintained by the Spanish led to widespread resentment. The memory of the once-glorious Inca Empire still lingered among the indigenous people. The reverence for the Inca past was not just an ode to its bygone splendor but a potent reminder of a time before Spanish subjugation. Tupac Amaru, claiming direct descent from the last Inca rulers, embodied this legacy. As economic hardships and political frustrations grew, many began to view him as a symbol of hope and a potential leader in the fight against Spanish oppression, setting the stage for the monumental rebellion that would soon unfold.

The late 18th century in South America, particularly in the region which is today Peru, was marked by a complex interplay of economic distress, political discontent, and deep-seated local resentments. These multifaceted tensions created the kindling for Tupac Amaru’s rebellion, one of the most significant indigenous uprisings against Spanish colonial rule.

Economically, Spanish colonialism had imposed a heavy burden on the indigenous population and mestizos alike. The repartimiento system, a form of labor draft, forced native communities to supply workers for mines and other colonial enterprises. While this system was officially abolished in the mid-18th century, it was replaced by economic policies that continued to exploit indigenous labor. The Bourbon Reforms, aimed at increasing colonial revenue for the crown, resulted in higher taxes and stricter controls over the indigenous and mestizo populace. These taxes disproportionately affected the lower classes, creating widespread economic hardship.

Politically, the Bourbon Reforms sought to consolidate power and reduce the influence of Creole elites, leading to increased dissatisfaction among the local leadership. The crown’s attempt to centralize authority, combined with the marginalization of Creoles in administrative positions, fostered resentment and a sense of alienation. This centralization of power often manifested in policies that were out of touch with the realities and complexities of local life, further widening the chasm between rulers and the ruled.

At a local level, cultural and racial tensions exacerbated the situation. Spanish officials and Creoles frequently looked down upon indigenous culture, and the forced labor systems maintained by the Spanish led to widespread resentment. The memory of the once-glorious Inca Empire still lingered among the indigenous people. The reverence for the Inca past was not just an ode to its bygone splendor but a potent reminder of a time before Spanish subjugation. Tupac Amaru, claiming direct descent from the last Inca rulers, embodied this legacy. As economic hardships and political frustrations grew, many began to view him as a symbol of hope and a potential leader in the fight against Spanish oppression, setting the stage for the monumental rebellion that would soon unfold.

The Uprising of Tupac Amaru

Tupac Amaru’s uprising, which began in 1780, is one of the most significant indigenous revolts in the history of colonial South America. Rooted in longstanding grievances against Spanish colonial policies, including the heavy burdens of taxation and forced labor, the rebellion was not just an isolated outburst of anger, but rather a culmination of decades of oppression felt by the native populace.

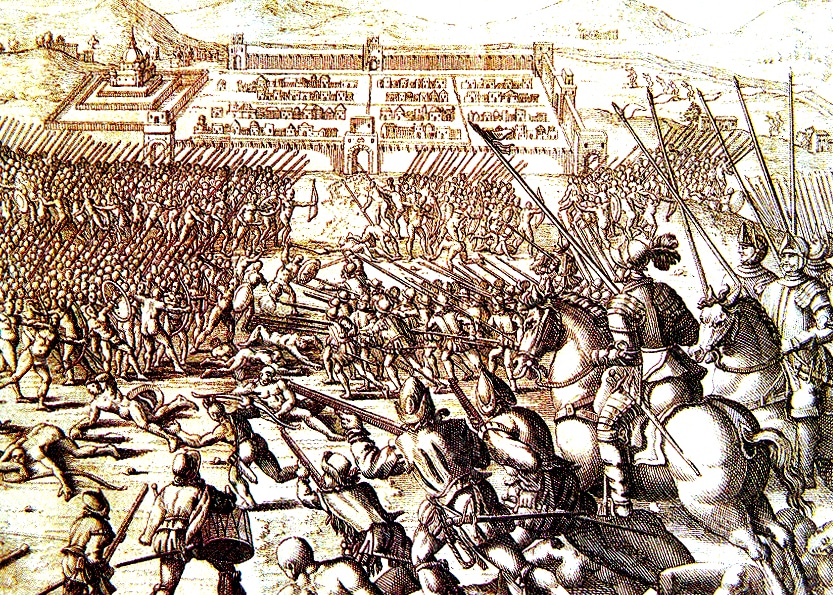

The spark that ignited the uprising was the maltreatment of indigenous workers by Spanish colonial authorities. The event that symbolically began the rebellion was Tupac Amaru II’s arrest of Antonio Arriaga, a particularly cruel corregidor (a local colonial administrator responsible for collecting tribute and labor drafts) in Tinta. On November 4, 1780, Arriaga was captured, tried, and then executed by Tupac Amaru II, who publicly announced his intention to overthrow the Spanish rule and reinstate the Inca Empire.

Tupac Amaru II’s troops, primarily composed of indigenous fighters, relied on a mixture of traditional Andean warfare tactics and adaptations in response to Spanish military strategies. One of their most notable strategies was leveraging the intricate knowledge of the rugged Andean terrain. By capitalizing on their familiarity with the high-altitude environment, Tupac Amaru’s forces could organize ambushes, quick raids, and swift retreats, often catching the Spanish off guard.

Moreover, the rebels utilized guerrilla-style warfare, avoiding direct confrontations when the odds were unfavorable. Instead, they focused on hit-and-run tactics, trying to wear down Spanish forces and supply lines over time. The indigenous warriors primarily wielded traditional weapons, such as slingshots, bows, and maces, but they also began to adopt some firearms and horses as the rebellion progressed. Their deep commitment to the cause, rooted in cultural and spiritual beliefs, was another driving factor in their resilience and determination to resist Spanish colonial oppression, making them formidable opponents despite their often technological disadvantages.

On the Spanish side, the initial response was marked by confusion and underestimation of the rebellion’s strength and reach. However, as the revolt spread, Spanish colonial forces, reinforced by loyalist indigenous troops, employed a combination of standard European warfare tactics, including cavalry charges, and siege tactics.

Before the major confrontation at the Battle of Cuzco, Tupac Amaru II and his forces managed to reclaim significant territory from the Spanish. This was an assertion of indigenous control and a direct challenge to Spanish colonial dominance. Starting with the capture and execution of Antonio Arriaga, a highly unpopular Spanish corregidor, in the town of Tungasuca, the rebellion quickly gained momentum. As word spread of Tupac Amaru’s defiance and the rebel army’s successes, more regions began to rally to the cause.

Within a short period, the uprising spread through a vast area of the southern Andes, with regions such as Tinta and Sangarará falling into rebel hands. After their decisive victory at the Battle of Sangarará against a well-equipped Spanish army, the morale of Tupac Amaru’s forces soared. This triumph served as a beacon, galvanizing support and swelling the rebel ranks. Towns and villages that had once been under Spanish control began to assert their independence, pushing out Spanish officials and aligning themselves with Tupac Amaru’s movement. This growing dominion not only bolstered indigenous spirits but also sent shockwaves throughout the Spanish colonial establishment, setting the stage for the critical Battle of Cuzco.

The Beginning of the End

One of the major engagements of the rebellion was the Siege of Cuzco in 1781. Tupac Amaru’s forces, numbering around 60,000, laid siege to the city but were unable to capture it due to its formidable defenses and the strategic use of artillery by the Spanish. The failure to capture Cuzco marked a turning point in the rebellion, as it stalled the momentum built by the indigenous forces. Casualty figures for the siege vary, but thousands are believed to have perished.

The Battle of Combapata was another pivotal confrontation in the rebellion led by Tupac Amaru II against Spanish colonial rule in South America. Taking place in 1781, the battle represented a significant strategic endeavor by the rebels to challenge the might of the Spanish Empire and liberate the indigenous peoples from colonial subjugation.

Tupac Amaru II had amassed a considerable force, with some estimates suggesting he had around 50,000 to 60,000 indigenous fighters, though actual numbers might have varied. They were armed primarily with traditional weapons, lacking the firepower and discipline of the Spanish troops. The Spanish, on the other hand, had a smaller but much better-equipped and trained force, relying on their cavalry, firearms, and cannons. At Combapata, the two sides clashed fiercely, with Tupac Amaru II hoping to leverage his superior numbers to encircle and overpower the Spanish. However, the Spanish troops, led by seasoned commanders, utilized their artillery effectively and exploited the terrain and the lack of experience in the rebel ranks.

The outcome was a devastating defeat for Tupac Amaru II’s forces. The rebels suffered heavy casualties, with thousands killed in the confrontation, while the Spanish losses were considerably lower. The Battle of Combapata not only dealt a significant blow to the morale of the indigenous resistance but also shifted the momentum in favor of the Spanish. Following this decisive Spanish victory, Tupac Amaru II’s rebellion faced even greater challenges, culminating in his eventual capture and the suppression of the revolt. The battle underscored the challenges that indigenous uprisings faced when confronting well-armed European colonial powers, even when they enjoyed numerical superiority.

The failures at Cuzco and Combapata displayed the fervor and might of Tupac Amaru’s forces but also exposed their vulnerabilities. The Spanish, although initially caught off guard by the magnitude and intensity of the indigenous uprising, began to strategize a more coordinated response after these confrontations. Recognizing the seriousness of the threat to their colonial dominion, the Spanish Crown poured resources into the region, mobilizing experienced troops from various parts of the empire to quell the rebellion.

Jose Antonio de Areche, the royal commissioner, was dispatched with the singular task of suppressing the uprising. Areche implemented a dual approach: a brutal military crackdown and a propaganda war. Spanish forces began to employ a scorched earth policy, targeting not just active rebels but also their supporting communities. This aimed to demoralize the indigenous population, breaking their will to fight by showcasing the might and ruthlessness of the Spanish Crown. Alongside this, Areche’s administration distributed leaflets and utilized local churches to convey messages that painted Tupac Amaru as a traitor, not the savior he claimed to be. This propaganda aimed to sow doubts among potential supporters and fracture the broad coalition Amaru had built.

Despite winning major battles, Tupac Amaru II’s forces began to wane under the sheer weight of the Spanish military machine and the tactics employed by Areche. After the failed attempts to seize Cuzco and the defeat at Combapata, many erstwhile supporters began to believe that the rebellion might not succeed, leading to defections and betrayals. It was during this phase of dwindling support and increasing pressure from the Spanish forces that Tupac Amaru made the fateful decision to retreat to the region of Vilcabamba, a move that would lead to his eventual capture. This region, historically significant as the last refuge of the Inca Empire against the Spanish, became the site where Spanish forces surrounded and trapped Amaru. An indigenous curaca, loyal to the Spanish, betrayed Tupac Amaru, leading to his capture near the town of Checacupe. This marked the beginning of the end for one of the most significant indigenous rebellions in colonial Latin American history.

The Fate of Túpac Amaru the “Last Inca”

The execution of Túpac Amaru II, whose birth name was José Gabriel Condorcanqui, was both a brutal act of deterrence and a symbolic end to the largest indigenous uprising against Spanish colonization in the Andean region. On May 18, 1781, in the main plaza of Cusco, Túpac Amaru II was subjected to a horrifying public execution meant to send a clear message to all who might think of resisting Spanish rule in the future. The Spanish authorities attempted to dismember him using four horses, but when this method failed, they opted to decapitate and quarter him. His body parts were then dispatched to various regions as a chilling reminder of Spanish power and retribution.

The suppression of Túpac Amaru’s rebellion was characterized by immense brutality. Following his execution, a massive campaign of reprisals was launched against those who had supported or sympathized with the uprising. Thousands were subjected to torture, execution, forced labor, or exile. The Spanish colonial authorities, eager to ensure that such a revolt would never occur again, implemented a series of policies aimed at diminishing the influence and autonomy of the indigenous nobility and further entrenching Spanish dominance. This included banning indigenous customs, dress, and languages in many areas.

In the immediate aftermath, the rebellion’s suppression had the desired effect for the Spanish authorities. The stark display of imperial might and the ensuing repressive measures quashed any similar large-scale uprisings for the duration of Spanish rule in the region. But the uprising also highlighted the deep-seated grievances of the indigenous population and underscored the inherent instability of a system built on oppression.

ideasGraves, CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

In the long run, Túpac Amaru’s rebellion had profound implications. While it didn’t achieve its immediate goals, it instilled a sense of resistance and became a symbol of indigenous defiance against colonial oppression. This spirit would reverberate through subsequent movements for independence and rights across Latin America. Túpac Amaru himself would become an iconic figure, evoked in later years as a symbol of indigenous resistance and pride.

Today, the legacy of the uprising and Túpac Amaru II’s sacrifice is evident in the political and cultural fabric of many Andean countries. The rebellion has been a source of inspiration for various indigenous rights movements, and Túpac Amaru’s name is invoked as a symbol of resistance against oppression, not only in Peru but throughout Latin America. His enduring legacy is a testament to the power of resistance and the indomitable spirit of those who stand up against injustice.