Unveiling the Barbary Wars: Jefferson’s Bold Stand Against Pirates

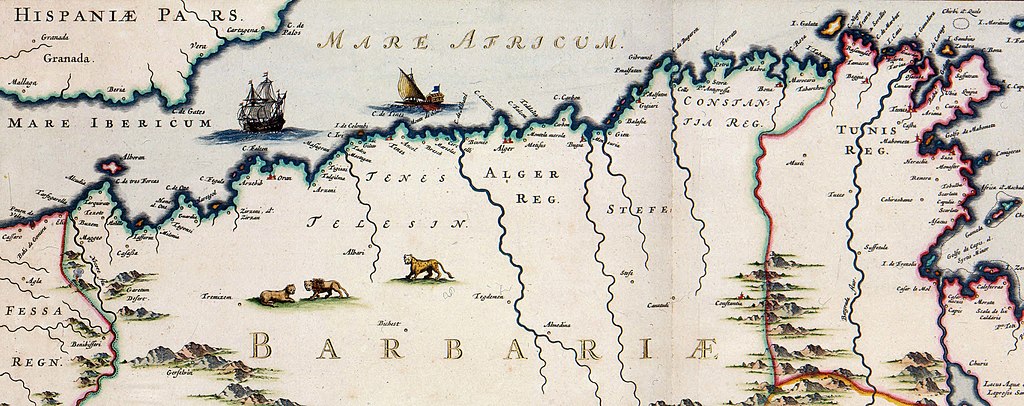

The Barbary Pirates of North Africa, based in Morocco, Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli, had raided shipping in the Mediterranean for centuries. With the support of their governments, these state-sponsored pirates would capture merchant ships and hold their crews for ransom, or demand an annual tribute to guarantee safe passage of a nation’s ships. Paying the tribute was often cheaper than waging war, so European powers had done so for decades. The newly independent United States no longer had the British Royal Navy’s protection and, after the American Revolution, began to experience pirate attacks on its merchant shipping.

When Thomas Jefferson became president in 1801, he decided that the US should stop paying tribute to the pirates. This decision led to a series of naval battles known as the Barbary Wars. Jefferson’s decision to stop paying the tribute was the first time the United States used military force abroad. It was a formative moment in American history and helped establish a new era of US foreign policy based on principles of sovereignty, strength, and self-determination.

The Rise of the Barbary Pirates

Barbary Pirates, or corsairs as they were often known, became a major force off the coast of North Africa during the 16th century. As semi-independent provinces of the Ottoman Empire (Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli) and later, independent Morocco, the North African coastal powers were built on the twin resources of plunder and tribute, with corsairs being armed, financed, and encouraged by their rulers. Armed with fast, maneuverable galleys, they patrolled the Mediterranean, capturing merchant ships, enslaving their crews and cargo, and raiding coastal cities. As new naval technology enabled them to range farther out into the ocean, they became bolder and began preying more heavily on European, and later, American shipping.

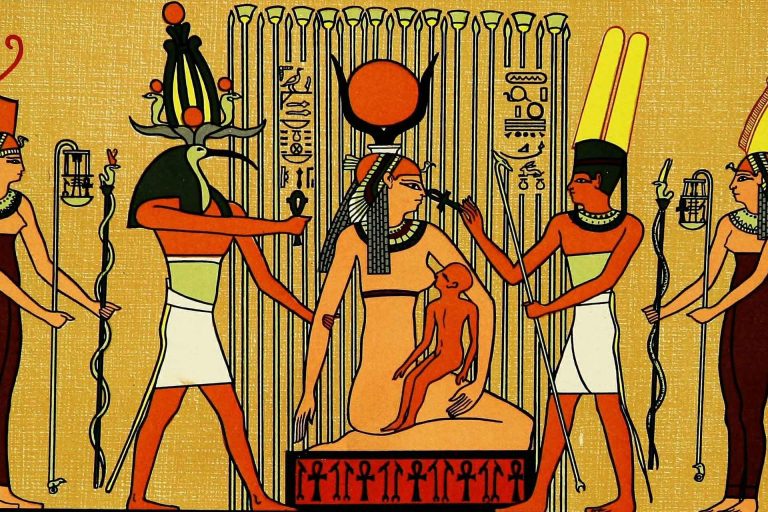

Raiding and piracy were officially licensed. All the Barbary States considered raiding an official enterprise of the state and were within their rights according to Islamic law to do so when at war with non-Muslim states. Captives taken on raids were generally held for ransom or were enslaved. If they were wealthy or important enough, they might be ransomed for cash, supplies, or diplomatic concessions. Others were sold as galley slaves for life. As the distinction between piracy and outright war was often deliberately obscured by the corsairs, it was difficult to address within traditional diplomatic means.

European states lacked a unified naval force and were often distracted by their land wars. As a result, most preferred paying tribute rather than entering into prolonged naval wars, a policy that Barbary leaders openly encouraged. This tribute took the form of annual bribes, the gift of ships to local leaders or their representatives, and other extravagant gifts to the rulers of the Barbary States in return for “peaceful” passage for European ships. Spain, France, Britain, the Dutch Republic, and others all paid tribute in this manner to avoid conflict, indirectly financing the corsairs. Even Papal naval fleets were not immune from attack, with the Vatican itself located in the heart of the central Mediterranean.

Exploits of the Barbary Pirates

The Barbary Pirates were also a significant threat to coastal settlements, with European villages from Italy to Iceland targeted in fast-moving raids where the inhabitants were abducted, killed, or ransomed. In one famous attack in 1631, nearly 100 men, women, and children were kidnapped from Baltimore, Ireland, and sold into slavery in North Africa.

Historians believe that an estimated 1 to 1.25 million Europeans were captured and sold into slavery between the early 1500s and 1800s by the Barbary corsairs. According to the book Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters, historian Robert C. Davis notes that these numbers are likely to be possible when averaged over multiple centuries of raiding. Other scholars debate the accuracy of the 1 million figure, but no one debates the scale and frequency of the kidnappings, which were a constant threat to European security and commerce.

Barbary pirates were indiscriminate in their targets, attacking ships from any nation they deemed had not paid a sufficient tribute. They commonly held hostages for ransom and forced their captives into labor, typically under harsh and violent conditions. These slaves rowed galleys, worked in quarries, or were sold in North African marketplaces. Survivors who were ransomed or escaped recall years of abuse; most of the captives never returned home. Memoirs of those who did were published throughout Europe and helped to fuel public sentiment against the corsairs.

In addition to their naval attacks, Barbary pirates targeted poorly defended European coastlines and towns as well. In addition to the raids in Ireland, they also sacked towns in Cornwall, the Balearic Islands, and southern France, and, in 1627, Iceland. European monarchies were often too busy fighting wars or managing domestic upheavals to expend the resources necessary for a military response—instead, many paid ransoms.

The economic impact on maritime trade was especially significant, as it was critical to both European and early American economies. Piracy caused insurance rates to increase, which discouraged commercial shipping. .

Some nations signed treaties with the Barbary States to make annual tributes in exchange for safe passage; others, like Spain and Portugal, opted for punitive naval campaigns against the pirate states with little success. The corsairs were a constant and extremely adaptable threat, able to take advantage of their unique combination of opportunism, state sponsorship, and maritime skill

The success of the Barbary pirates was as much a product of the geopolitical fragmentation of Europe and North Africa as it was of their own naval skill. A lack of coordination among European states meant the merchants were fair game for exploitation. It would take a new kind of power, a power unwilling to pay tribute, to disrupt the status quo—and that power would be the infant United States under Thomas Jefferson.

The Young American Republic and the Barbary Threat

In the aftermath of the American Revolution, the United States had been left high and dry. The Royal Navy no longer sheltered American merchant vessels from Barbary corsairs, and the new United States Navy was not yet created. With no way to protect American shipping, the United States was vulnerable to attack from Barbary pirates, whose predatory incursions in the Mediterranean threatened to humiliate the infant country and strangle its trade.

By the mid-1780s, Barbary corsairs had captured several American ships and sailors and began taking American crews hostage for ransom or enslavement. In 1785, Algerian pirates captured two U.S. ships, the Maria and the Dauphin, and enslaved their crews, which caused consternation and outrage in Congress, which was still cash-poor and lacked a military to respond. Instead, early American leaders sought to resolve the situation through diplomacy: the U.S. sent special envoys, such as John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, to parley with the Barbary leaders.

The first efforts focused on tribute payments, which Europeans had long used to buy peace from the corsairs. In 1796, the United States paid $40,000 and agreed to regular tribute to the Tripolitan ruler, in exchange for a nonaggression treaty. The U.S. also reached tribute agreements with Algiers and Tunis, agreeing to provide ships, supplies, and gifts to the three regimes. By this time, nearly one-sixth of the U.S. federal budget was being spent on payments to the Barbary states, a heavy burden for a government still solidifying its finances.

Jefferson, who was minister to France in the 1780s, had opposed the use of tribute as both “dishonorable” and an impractical drain on the government’s budget. He believed that “the longer we pay tribute, the more it will be expected.”

Jefferson was outvoted by Adams and other advocates for appeasement, who argued that it was better to pay for peace rather than risk bloodshed. The U.S. continued its appeasement policy for the rest of the 1790s, even as pirates preyed on American shipping and U.S. captives languished in slavery.

American public outrage at pirate attacks increased, and Congress began spending ransom money to free captives. In 1795, Congress set aside nearly $1 million to free American prisoners in Algiers and pay for ongoing protection. By the end of the decade, over 100 American captives had been released in this way. But as the problem was papered over, it was not solved, and by 1799, the Barbary States were ratcheting up their demands on the U.S.

With the problems unresolved, Jefferson, who was now president, faced a challenge when he took office in 1801. The young nation needed to protect its interests abroad without relying on European navies or appeasement, and the Barbary pirates became the means by which this was achieved. Jefferson took an aggressive approach to the threat, and war with the Barbary States ensued: the First Barbary War.

American frustrations with Barbary piracy were coming to a head, and with Jefferson as president, the stage was set for an American response.

Jefferson Takes a Stand

President Thomas Jefferson had a long-held conviction against paying tribute to foreign powers. Despite his compliance with previous negotiations, Jefferson believed that tribute was both unsustainable and dishonorable. He saw appeasement as a policy that only encouraged the Barbary States to be more aggressive and diminished the reputation of the American republic.

In early 1801, shortly after Jefferson’s inauguration, the Pasha of Tripoli, Yusuf Karamanli, demanded an increase in tribute from the United States. Jefferson refused to pay the increased demand, and Tripoli responded by declaring war on the United States on May 14, 1801. The decision by Tripoli to go to war with the United States was an extraordinary and shocking one. America was a young nation, and this was the first time it had been engaged in a declared conflict with a foreign power overseas.

Jefferson did not back down. Instead of acquiescing to the demands or sending more diplomats with bags of gold, he ordered a squadron of U.S. Navy ships to the Mediterranean. This was a historic moment in U.S. foreign policy. It was the first time the United States had used its military might to defend its rights and interests abroad. It was also the first time the United States had taken military action beyond its own borders.

Jefferson’s decision to send the Navy to the Mediterranean demonstrated his willingness to take a more assertive and independent stance in foreign affairs. He believed that the United States should not rely on European powers to protect its interests and that it should be prepared to defend itself by force if necessary. Jefferson’s move also reflected the growing power of the United States. In the late 1790s, Jefferson had established the Department of the Navy, and the United States had quietly built up a small but modern fleet of warships.

The decision to send the Navy to the Mediterranean was a risky move, but it paid off in the long run. The deployment of the Navy helped to protect American commerce in the Mediterranean and established the United States as a significant power in the region. The decision also set a precedent for future U.S. foreign policy, demonstrating that the United States was willing to use force to defend its interests abroad.

Jefferson’s decision to send the Navy to the Mediterranean was both a strategic and symbolic move. It was a clear message to both allies and adversaries that the United States was a power to be reckoned with. The move was a departure from the more cautious diplomacy of previous administrations and signaled a new era of American engagement in world affairs. The Barbary conflict would become the proving ground for this new approach to foreign policy, with the United States using its naval power to project influence and protect its interests across the world.

The First Barbary War (1801–1805)

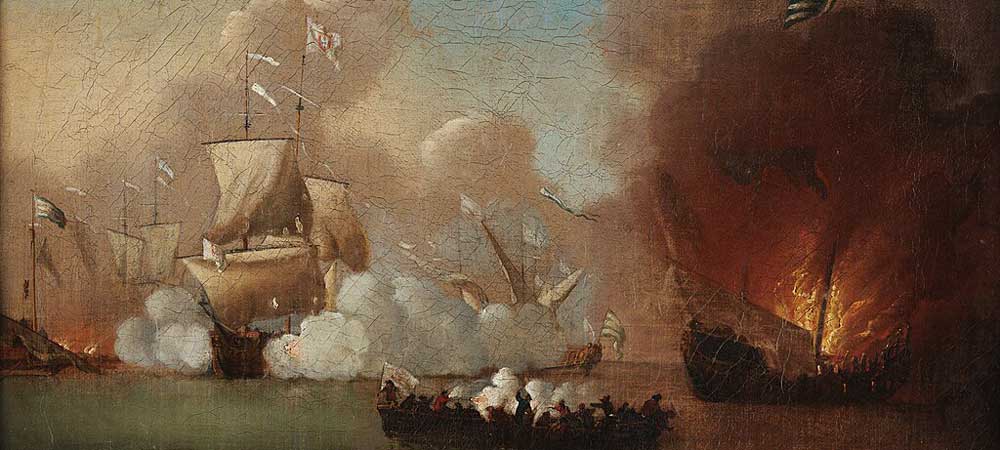

The First Barbary War was now in full swing. Jefferson’s naval presence in the Mediterranean forced the hand of the corsairs. The U.S. Navy blockaded the coast of Tripoli in an attempt to strangle the economy of the Pasha. A series of naval skirmishes and coastal bombardments ensued, each side probing the other’s mettle. Victory was far from certain, and the conflict revealed the strengths and weaknesses of America’s infant navy. Though small steps, these were the first battles fought by United States forces on foreign soil.

The momentum of the war changed in 1803 with the capture of USS Philadelphia. The American frigate was chasing a Tripolitan vessel when it ran aground near the harbor of Tripoli. Enemy forces quickly overran the Philadelphia, capturing her entire crew of over 300 men. The ship’s surrender gave the Pasha a naval prize, which he then had to refit and use in his own fleet. A small but stealthy force under U.S. Navy officer Stephen Decatur snuck into Tripoli in February 1804 and overran the Philadelphia, setting her on fire to prevent her capture. British Admiral Lord Nelson is quoted as saying that Decatur’s mission was “the most bold and daring act of the age.

The U.S. also decided to back a rebellion in Tripoli, hoping to dethrone the Pasha, Yusuf Karamanli, from power. They supported his exiled brother, Hamet, in a military campaign against the Pasha. A combined force of U.S. Marines, sailors, and Arab mercenaries was carried overland toward Derna in 1805. The subsequent Battle of Derna was the first recorded raising of the U.S. flag in victory on foreign soil, and served to rattle the Pasha further. Yusuf’s army was defeated in the field, and he was forced to negotiate.

Tripoli was now at the end of their rope. With the American navy preying on their shores, no revenue from piracy, and another rebellion to fear, Tripoli sued for peace in June 1805. The Treaty of Peace and Amity between the United States of America and the Regency of Tripoli ended the war, released American prisoners, and set no further tribute. The United States paid a ransom to end the war, but did so while keeping its pride and policy intact. It was a win for Jefferson.

The First Barbary War was a proving ground for the infant U.S. Navy, which began to show itself as a force to be reckoned with on the world stage. The war also brought a new foreign policy, in which the United States would no longer pay tribute. America would instead fight back against those who would plunder. Jefferson gambled with his decision to engage the Barbary States with naval force and won, setting a new tone for how the young republic would handle its foreign enemies.

The Second Barbary War (1815)

The First Barbary War had curtailed the pirate menace, but it would not stay that way for long. A resurgence in North African piracy came during the War of 1812. The United States was at war with the British when the Barbary States, especially Algiers, once again preyed on American merchant shipping. American merchantmen were seized and sailors sold into slavery as they had been in years past, the U.S. Navy having been redeployed to home waters to deal with the British. Peace was restored to a degree, but by 1815, the situation had deteriorated to the point where the Americans had to act again.

President James Madison, fresh from his election victory, ordered a powerful squadron of ships into the Mediterranean to restore order. The new American President, flush with a hard-won second term, gave command of the ten warships to Commodore Stephen Decatur, the newly minted hero of the First Barbary War. The squadron was to be the most potent force ever sent to sea by the United States and would put an end to piracy and tribute payments once and for all. In less than a month, Decatur’s ships had captured Algerine ships and placed the Dey of Algiers under siege.

On June 30, 1815, Stephen Decatur, with a show of force from his squadron, concluded a treaty with Algiers on very favorable terms to the United States. It demanded the release of all American captives, the payment of compensation for lost ships, and a permanent end to tribute payments. Similar treaties were quickly arranged with Tunis and Tripoli. The war lasted less than two months, but it would have permanent effects both at home and abroad. The Barbary States would never again threaten American shipping, and other European nations that had previously paid tribute would follow the American example.

The Second Barbary War marked the end of state-sponsored piracy in the Mediterranean and demonstrated that the United States Navy had become a world-class naval power. More importantly, it showed that the time for the United States to “buy peace” had passed. The new nation had found its voice, and it would not again be bought off with tribute. Decatur’s victory and the resulting peace signaled a new day in American foreign policy.

Legacy of the Barbary Wars

The Barbary Wars had significant long-term implications for the United States. Militarily, these wars were the first large-scale overseas operations for both the U.S. Navy and the U.S. Marine Corps, setting precedents and shaping their future roles in American defense and foreign policy. The experience gained during these conflicts highlighted the necessity of a robust naval presence and spurred the development of maritime infrastructure, further professionalizing the country’s military service.

The conflicts marked a shift in American foreign policy, moving from acquiescence to the active defense of national interests. The United States, having shown a willingness to engage militarily rather than submit to extortion, emerged from the Barbary Wars with a newfound sense of its role in protecting its trade and citizens abroad. Jefferson’s refusal to negotiate or pay tribute to pirates became a policy stance that resonated in future American foreign policy decisions, reinforcing a tendency towards assertiveness over appeasement, especially during the formulation of the Monroe Doctrine and subsequent U.S. military interventions.

Diplomatically, the Barbary Wars represented the end of the European tradition of paying tribute to Mediterranean powers, as the United States, a former European colony, refused to follow suit. The American response, rooted in the Enlightenment ideals of freedom and self-determination, set a new tone in international relations, one that some European powers found challenging to ignore or reconcile with their own diplomatic practices. While European countries continued to grapple with piracy and tribute payments, they were forced to reconsider the sustainability and legitimacy of these practices amid American resistance. The conflicts ended a centuries-old tradition of European tribute payments to the North African states.

The cultural impact of the wars on the United States has also been lasting. The U.S. Marine Corps hymn includes the line “To the shores of Tripoli,” a reference to the Marines’ early involvement in the First Barbary War. This line, and the hymn as a whole, serve as a tribute to the bravery of the Marines and a reminder of the nation’s willingness to project power overseas. The Barbary Wars became a formative chapter in the lore of the Marine Corps and the Navy, contributing to their identities as institutions that defend American interests far from home.

Politically, the Barbary Wars elevated national figures like Thomas Jefferson and Stephen Decatur, whose decisions during the conflicts helped shape their legacies. The successful conclusion of the wars became part of the narrative of the young republic’s emergence as a significant power. Public opinion and national morale were positively affected, as victories in these conflicts demonstrated that the United States could hold its own against more established powers, further unifying the country around its achievements.