Vlad Tepes: Madman or Mastermind of Medieval Terror

Was Vlad Tepes a bloodthirsty monster, a power-crazed madman, or a master of psychological warfare? To his enemies he was a monster, to his people a hero, and to history a prince whose story has passed into legend: Vlad Tepes, Dracula, the Impaler.

This notorious son of Wallachia has been immortalized in more bloodthirsty legends than any other figure from Medieval Europe, but what was the real story behind the myth? The real Vlad Tepes was both maniacal and a pragmatist, a man who understood the power of fear and made it his most potent weapon.

It is said that when Sultan Mehmed II finally withdrew his forces from Vlad’s capital, he declared to his commanders, “What can we do against a man who would do such things to his people?”

To understand how a local lord became a living symbol of horror, we will need to examine his early life as an Ottoman hostage, his bloody ascent to the Wallachian throne, and his wartime dealings with both domestic rivals and foreign invaders.

Origins of a Prince Shaped by Betrayal

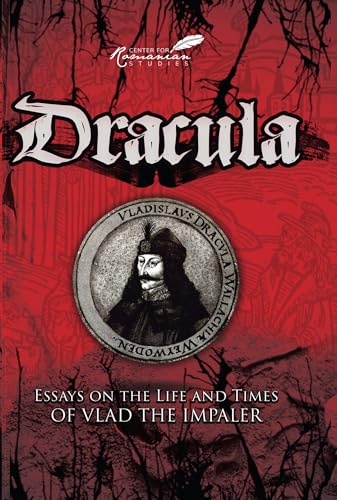

Vlad Tepes was born into the House of Drăculești, a branch of the Wallachian nobility. His father, Vlad II Dracul, had been elected to rule Wallachia in 1431. He received his notorious moniker in 1431 after being inducted into the Order of the Dragon. This chivalric order, founded by Emperor Sigismund of Luxembourg, was devoted to defending Christendom against the advance of the Ottoman Turks. In taking his oath, Vlad Dracul had pledged to defend Christendom and its people at all costs, bringing his family into the middle of one of the most tumultuous conflicts of the 15th century.

In 1442, with the Ottoman menace on the rise, Sultan Murad II sent for Vlad Dracul to his court. The Sultan took Vlad’s sons, Vlad and Radu, as political hostages in exchange for his safe return to Wallachia. Their father was thus able to return to Wallachia under the grudging terms of an Ottoman non-aggression pact, but the young princes were held as hostages to ensure their father’s good behavior.

Vlad and Radu were still boys when they were separated from their family and sent to the heart of the Ottoman Empire. Everything about the Sultan’s empire was strange to them: its language, its faith, its customs. The sultan’s court at Edirne was a palace of wonders, but they were foreigners in that world, little more than prisoners.

The Ottoman court influenced the two brothers in starkly different ways. Radu, later called “Radu the Handsome,” was perfectly content to become Turkish. He embraced Islam, found his place at court, and became close to the sultan’s son, Mehmed II. Vlad, on the other hand, could not abide the place. He hated everything about the empire, which seemed to him to be little more than a glittering cage, and he never overcame his animosity. While Radu saw an empire ripe for diplomacy and advancement, Vlad saw a foe who used flattery and underhanded tactics to get what he wanted.

Captivity at the court of Murad II did one thing for sure to young Vlad: it taught him to fear. Taken from his home, his people, and the trust of even his father, Vlad was stripped of everything but his will to live and his pride. He would later rule by fear and employ cruelty as a calculated tool to achieve his goals, likely drawing inspiration for these actions from his early life in the Ottoman Empire.

Alexandru Simon writes, “Captivity did not break Vlad—it redefined him.” He spent his childhood and adolescence in the sultan’s court, never quite Turkish enough to be trusted, never quite foreign enough to be comfortable. The seeds of his reign were sewn during those years of Ottoman captivity.

Further betraying the young Vlad was the later murder of his father and older brother at the hands of Wallachian boyars. These powerful nobles found it more convenient to defect to the Ottomans than to serve Vlad Dracul and his sons. Vlad Dracul’s uneasy alliance with the Ottomans and his perceived softness toward them made him vulnerable. His death in 1447 left young Vlad without illusions of honor or brotherhood. He returned to Wallachia not as a prince-in-waiting but as a man who had seen up close the cost of complacency.

Vlad would later be a ruler who trusted no one, who acted first and struck hard, who would use cruelty not for its own sake but as a deliberate tool of terror. He became the figure he did because of the early betrayals he had experienced.

Vlad Tepes’ First and Second Rise to Power

Political intrigue and power struggles followed. The death of Vlad II Dracul and his eldest son Mircea created a vacuum in Wallachia. With Hungarian backing, rival boyars plotted the family’s demise in 1447. Mircea was reportedly blinded and buried alive. Vlad II was ambushed and killed outside Târgoviște. Vlad Tepes, then a political hostage of the Ottomans since 1442, now found himself heir to a throne run red with blood.

Late in 1448 Vlad capitalized on an opening. With Ottoman support, he made a move for the throne of Wallachia. The effort lasted but a few months. But his first reign set the tone for what would follow: friends were temporary, foes were many, and only the callous thrive. Ousted by rivals backed by the Hungarians, Vlad would spend the next few years in Moldavia and Transylvania working to re-establish himself.

In 1456, with Hungarian military support, especially that of the famed Hungarian regent John Hunyadi, Vlad made another successful bid to rule Wallachia. He bested Vladislav II in battle and reclaimed his title. This second reign marked a turning point. Vlad had been burned by the treachery that had felled his family, and he would no longer be the first to pardon or accept disloyalty, whether from foreign powers or his own boyars.

Revenge and Ruthless Order

Beginning with the Easter Massacre of 1457, Vlad viewed terror as the cornerstone of his power and authority, not the regrettable byproduct of it. For this feast day celebration, he invited hundreds of the most powerful boyars in Wallachia to a banquet in his new capital of Târgoviște, then had his soldiers round them up. Vlad had the elders impaled; the young men were spared and instead forced to march to Poenari, where they would rebuild the fortress. He continued to impale thousands, according to Greek chronicler Laonikos Chalkokondyles, to rid the land of disloyalty and treachery.

Fear was Vlad’s most potent political instrument. Vlad ruled with an iron fist. Authority was his to wield, through the public spectacle of punishments and executions, and by constant surveillance over every corner of Wallachia. Peasants and aristocrats were held to the same unbending standard. Stealing a loaf of bread was punishable by impalement.

“He was very cruel,” the German pamphlet The Story of a Bloodthirsty Madman Called Dracula said, “but he achieved great things.” It was said that a man could leave a gold coin in the street without it being stolen—a sentiment from several fifteenth-century accounts. The Russian Skazanie o Drakule voevode boasted, “He placed a cup of gold at a public fountain, and no man dared steal it.”

Vlad was no less harsh with his enemies outside Wallachia’s borders. When the Transylvanian Saxons of Kronstadt refused to swear allegiance to Vlad, rejected his trading edicts, and lent their support to rival claimants, Vlad had their trading posts and merchant towns burned to the ground. The Saxons who were captured were impaled by the hundreds. In Transylvania as well as within Wallachia, Vlad’s acts were never arbitrary; they were meant to terrify his enemies into submission, discourage subversion, and serve as a reminder that he would not be opposed.

In regions where allegiances were often fickle and Ottoman pressure was constant, brutality became a necessary measure to maintain stability. He put an end to bribery and insubordination, discouraged dissent, and secured Wallachia’s borders—but he did so through force, not through politics or diplomacy. As historian Constantin C. Giurescu wrote, Vlad “restored order through fear, and his authority was absolute.”

When Vlad Tepes died, after only two years on the throne, he had changed Wallachia. He avenged his father and brother, overcame the treacherous boyars, and earned the respect and dread of foreign enemies and his own people. He was either a madman who left a bloodstained legacy or a necessary leader who boldly imposed order upon a nation that had no idea how to govern itself except in chaos. Whatever he was, one thing was sure: in Vlad’s Wallachia, peace was only achieved through fear.

War with the Ottoman Empire

By the early 1460s, the Ottoman Empire had cast a shadow over Eastern Europe. Sultan Mehmed II, the conqueror of Constantinople, was setting his sights on Wallachia. The small principality was technically a vassal of the Ottoman court, expected to pay tribute to the Sultan’s court. However, Vlad Tepes had no intention of continuing these payments. Haunted by his time in captivity and driven by an unquenchable thirst for vengeance, Vlad defiantly cut off the tributes to the Ottoman Empire. His rejection was more than mere words. Vlad Tepes simply stopped paying and openly announced his resistance to the Ottomans, thrusting Wallachia into a direct conflict with one of the era’s most formidable powers.

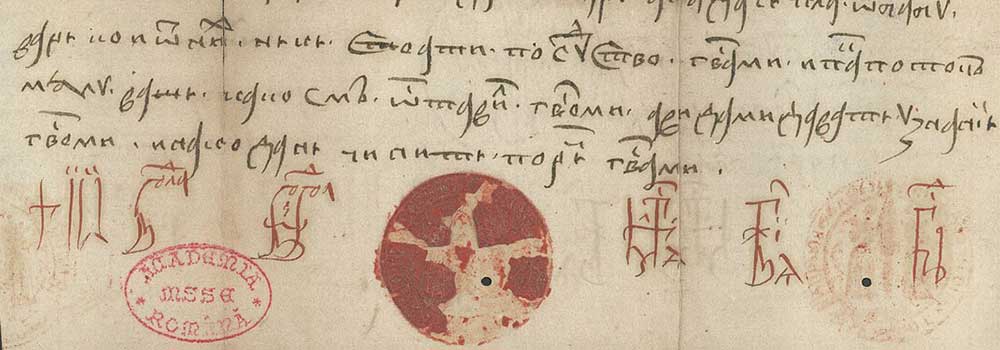

Vlad Tepes would not wait for the Ottoman Empire to attack, however. In the winter of 1461, Vlad Tepes led daring raids across the Danube River into Ottoman-occupied territories in what is now Bulgaria. In a letter to the King of Hungary, he boasts, “I have killed peasants, men and women, old and young… We killed 23,884 Turks without counting those we burned alive in homes.” These preemptive raids against the Ottomans were meant to sow panic among the Sultan’s vassals while denying the enemy valuable time to gather forces.

The initial impact of Vlad’s surprise raids was remarkable. Vlad’s men burned villages and outposts, massacring Ottoman soldiers in the process, and advanced deep into enemy territory. They pillaged without mercy, using speed, the element of surprise, and intimate knowledge of the land to catch the Ottomans off guard. Vlad’s tactics in the first stages of his campaign won him a mixture of admiration and fear among the region’s other Christian leaders. He also ensured that the Ottomans would strike back hard and fast. In response to Vlad’s raids, Sultan Mehmed II mobilized a vast army to bring Wallachia to heel.

In June 1462, a large Ottoman army numbering over 90,000 men crossed the border into Wallachia. Vlad Tepes, meanwhile, could put only 15,000 troops into the field. He knew that he stood little chance of besting Sultan Mehmed II’s veterans in a traditional field battle. Vlad Tepes instead opted for a scorched-earth campaign of deception and attrition.

Vlad Tepes met the massive Ottoman army not on the battlefield but with a campaign of sabotage and guerrilla warfare. He ordered his men to burn fields and crops, poison wells, and leave the Ottoman army without the resources they needed to fight. These tactics not only slowed the invaders but left them vulnerable to disease and famine. Though he was heavily outnumbered, Vlad’s intimate knowledge of his homeland and cruel determination to avoid defeat made Wallachia a hard place for the Ottomans to occupy.

Many of the battles Vlad Tepes fought were not large set-piece engagements but skirmishes fought in the forests and mountains of Wallachia. Vlad Tepes personally led his men into battle and gained a reputation as a fierce fighter and master horseman. His forces would make quick strikes and then disappear into the wilderness. Vlad’s use of hit-and-run tactics transformed his conflict with the Ottomans into a prolonged and grueling campaign that eroded Ottoman morale and their willingness to continue the fight.

This was not conventional warfare, but a purposeful form of resistance. Fueled by a desire for revenge and a stubborn will to avoid defeat, Vlad Tepes made Wallachia’s own rugged landscape into a weapon and himself into its fierce champion.

While Vlad Tepes could not ultimately defeat the Ottomans, his efforts did buy him time and demonstrated to the Sultan that Wallachia was not as easily taken as it may have first seemed. Vlad Tepes also showed the rest of Europe that, even against a colossus like the Ottoman Empire, resistance was possible. His brutal campaign against the Ottomans left Wallachia bloodied but unbowed and cemented Vlad Tepes’ own place in history both as an agent of terror and a symbol of defiance.

Psychological Warfare: Vlad’s True Weapon

Two infamous episodes–the Night Attack at Târgoviște and the creation of the so-called “Forest of the Impaled”–prove how he used fear as a weapon of war. In both cases, his aim was not simply to defeat the Ottoman Empire in battle, but to petrify them. Sultan Mehmed II, despite leading a large and powerful army, was forced to face a horror so deliberate and calculated that it unnerved even the toughest of soldiers.

The Night Attack at Târgoviște (1462)

The fateful night of June 1462 would become one of the most legendary ambushes in medieval history. Vlad Tepes, with a select group of his soldiers, infiltrated the large Ottoman camp near Târgoviște while it was still dark outside. Equipped with information from his spies and a thorough knowledge of the Ottoman camp layout, Vlad set out not to annihilate the enemy but to confuse and terrify them. His men, moving silently, cut through sleeping guards and set fire to tents. One account of the event describes it by saying, “men stumbled from their sleep only to be met with daggers and flames.”

In the chaos of that terrifying night, Ottoman troops were awoken by the noise of torches and the cries of their fellow soldiers. Men killed other men by mistake in the darkness; assassins found their way into the center of the Ottoman camp to dispatch important leaders. Vlad himself was supposedly one of the men who made it into the center of the camp in an attempt to find and kill the Sultan. He failed to find and kill Mehmed II, but his efforts did not go without cost. Exhausted and terrified, the Ottoman army lost its cohesion and aggression. Rumors about supernatural intervention or demonic support plagued the camp.

What was special about this surprise attack, though, was not its violence, but its implications. Vlad was not an army to beat the Ottomans in an open fight, and he was fully aware of it. By proving that even their camp in the center of Wallachia was not a safe place, he broke their confidence. He showed them that he did not have to wait for the Ottomans to attack him—he could hit them from behind, in their sleep, and he would do it again if he had to. He would make every moment of their campaign a torment, and no one in the army was safe.

Mehmed II was able to rally his forces and continue the campaign, but it was no longer the same as it had been before the Night Attack. His army suffered minimal losses, but its spirit was crippled. Nightfall now inspired dread in the hearts of the Ottoman soldiers, and every sound was the product of a deadly and vengeful Wallachian ready to strike. The Night Attack may not have won the battle, but it had sown a seed of doubt in one of the most fearsome fighting machines of the 15th century.

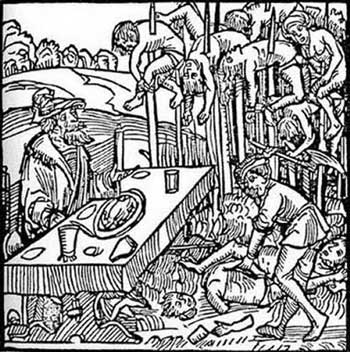

The Forest of the Impaled

If the Night Attack was a tactical victory, a blow to Ottoman morale, Vlad had something far more sinister in store for them just outside Târgoviște. As Mehmed’s army marched on, they were confronted with a bizarre and sinister spectacle: thousands upon thousands of impaled corpses, their bodies fixed upon tall wooden stakes as a fence for the damned. The rows of naked torsos and hacked-off limbs went on for miles. Modern historians have conservatively estimated the number of Ottoman prisoners who were executed in this manner at 20,000. It was a battlefield, but it was also a monument.

The sight was so shocking that it unnerved even the battle-hardened Mehmed II. “What can we do with a man who does such things?” the Sultan supposedly asked one of his chroniclers. He ordered his army to turn back a short time later. The rows and columns of impaled bodies, men, women, and children, were arranged so that the highest stakes impaled the highest-ranking victims. The wood bore its grisly message as clearly as the blades had cut. This was not the last word in butchery—this was psychological warfare on an epic scale, the point of which was to turn a battle in its tracks.

The forest of death Vlad constructed was not the product of insanity, but of a keen understanding of his enemy. He knew the Ottoman forces were as dependent on psychological dominance as they were on physical strength. By turning the very land into a living nightmare, Vlad inverted the equation. His own became an abyss of fear where no victory would come cheaply. To the Ottomans, Wallachia was no longer just an errant vassal state to be conquered—Wallachia was a place of terror, ruled by a man not bound by the rules of war. And that is precisely how Vlad wanted them to see it.

Perception: Monster, Hero, or Strategist?

Vlad Tepes’s reputation depends mainly on who is telling the story. In Western Europe, particularly in German-speaking countries, he was demonized as a sadistic brute. Pamphlets printed in the late fifteenth century recount harrowing tales of impalement and mutilation, even cannibalism. One popular story says that Vlad “lunched among forests of the impaled.” These often exaggerated and sensationalized accounts were some of the first instances of mass-produced media and contributed to a lasting image of Vlad as a monstrous figure.

In the East, especially in Romania and the Balkans, Vlad’s story is very different. He is remembered as a strong and righteous ruler who restored order to a lawless land. Folk tales celebrate his strict discipline and unwavering will. His use of terror was seen not as madness, but as necessary to maintain justice and protect Wallachian independence.

The Ottoman chronicles tell a different story. Vlad is remembered as a fearsome and dangerous enemy. He challenged the power of Sultan Mehmed II, refused to pay tribute, and raided deep into Ottoman territory. His tactics – including psychological warfare and scorched-earth retreats – made him both infamous and respected. The Ottomans saw him as a threat to their power, but they also acknowledged his skill as a tactician. Vlad’s use of fear and symbolism gave him an advantage against overwhelming odds.

Fall of a Prince: Radu, the Ottomans, and Vlad’s Imprisonment

After the unsuccessful Ottoman invasion of Wallachia in 1462, Sultan Mehmed II retreated the majority of his forces back to Constantinople. Nevertheless, he did leave behind a considerable force, not consisting of Ottoman Turks, but rather of Vlad’s own younger brother, Radu the Handsome, and the vassal troops supporting him. Radu’s forces were left in Wallachia with a clear mandate – to retake the throne from Vlad and to place a more Ottoman-friendly prince upon it.

The invasion, however, was not immediately a military one. Radu began a war of politics and words against his elder brother, sending his emissaries and letters across Wallachia that threatened another, more powerful invasion of the entire Ottoman Empire, should Vlad remain on the throne for any longer. Vlad was still not yet defeated, and in the coming months, he was able to defeat both Radu and his Ottoman vassals in two separate campaigns. However, while still in the field with his army, Vlad was unable to muster full support to his cause.

Radu had already begun the process of earning the support of the boyars and the burghers, promising safety, continuation, and peace to a nation that had suffered greatly under the campaigns of Mehmed II. Slowly, but surely, support for Vlad Tepes began to wane, not on the battlefield, but on the level of words and assurances. Radu had promised a return to stability and tradition, whereas Vlad was now viewed as an agent of chaos and retribution. In a political sense, Vlad was isolated and forced to flee. Loyalty to him had not yet been bought, but had been lost.

In the winter of 1462, the majority of the Wallachian nobility defected to Radu’s side. Vlad, on the run from his brother and his allies, took up a short-lived campaign of evasion and distraction in the Carpathian Mountains, before making for the Hungarian borders in the hope of some assistance from the Hungarian court and his erstwhile ally, Matthias Corvinus. Waiting, however, for the Hungarian military to come to his aid was a weak proposition, even if Matthias was ever inclined towards such a course of action. Vlad’s only recourse, in the meantime, was the defection of the Saxons.

Radu, a canny and diplomatic individual himself, had made an interesting proposition to the burghers of Brașov, a powerful center of Wallachian industry and commerce. Radu had promised the burghers of Brașov the confirmation of all of their existing commercial privileges with Wallachia, along with a considerable sum of 15,000 ducats as a sign of good faith.

This clever move effectively blunted whatever remaining support Vlad was to muster in Transylvania and Hungary as well, as in the midst of this political maneuvering, Albert of Istenmező, an essential political functionary in Hungarian governance, had suggested to the Saxons that they make common cause with Radu, who would be the most stable option for a Wallachian prince. Vlad Tepes was now politically isolated and outmaneuvered, still in the field and with no guarantee of Hungarian support.

As if all this had not been enough, by the time Vlad could do little but make a play for Hungarian support, Matthias had had Vlad arrested on suspicion of treason. Vlad Tepes was imprisoned by the end of the year, according to the Hungarian king’s own account, based on forged letters that implicated him as a secret ally of the Ottomans. These charges, though probably untrue, provided Corvinus with a politically and diplomatically satisfying explanation as to why Vlad had been removed from power. Vlad would be exiled from Wallachia for over a decade, imprisoned at Visegrád and effectively out of any political or military influence.

The imprisonment would mark a turning point in Vlad’s political career and reputation. Supporters would take it as a sign of his victimization and betrayal by both foreign and domestic allies. At the same time, detractors would have been content to see his fall from grace as retribution for his crimes, real or imagined. Either way, the removal of Vlad from the Wallachian political equation allowed the Ottoman Empire to make a more direct inroad into Wallachia, with Radu’s rule cementing a political buffer in the south for the next decade and more.

Radu, however, was never a figure of quite the same respect and fear as Vlad was. The defection of Wallachia to an Ottoman-friendly prince was not equivalent to complete conquest or occupation. Still, it did signal a shift in the tides of conflict and the difficult position that Wallachia, as a state, had found itself in, serving as a buffer between three larger powers.

Vlad, despite his machinations and successes, was but a temporary fix for Wallachia’s geopolitical position, and his eventual return to the political stage could never quite right the course that had shifted so suddenly from victory to imprisonment. Even so, his later return to rule and eventual death are stories of a far-diminished political influence, though still potent in its own ways.

The fall of Vlad Tepes from his position of power remains one of the most intriguing aspects of his life and rule. As with most things about Vlad, history had distorted and colored his reputation both for good and for ill, and even today, his downfall from power often serves as a more interesting footnote than the rule itself. It is a strange fall from grace, however, to go from the victor of battle and of the battlefield to the conquered subject and prisoner of another. The drama of that short-lived campaign of evasion and distraction is, for all of its shortness, one of the more memorable chapters of Vlad the Impaler, the man and the myth.

Third Rule and Death of Vlad Tepes

Matthias Corvinus of Hungary, eventually acknowledged Vlad Țepeș as the legitimate ruler of Wallachia. He bestowed the title of prince on Vlad and his brothers and later he was given the court title of acomes, but he did not provide Vlad with an army to retake his throne. Vlad was under a half-hearted and uneasy protection of Matthias Corvinus in Pest, and his character did not mellow. According to Slavic sources, a raid by some soldiers in his house to catch a thief, resulted in Vlad having the commander of these soldiers hanged, because he had violated his house without permission. In June 1475, Vlad moved to Transylvania and he attempted to take up residence in Sibiu.

This did not last long, as his reign was marked by constant maneuvering by local factions for and against the Ottomans. Vlad was living in poverty and obscurity. Corvinus occasionally gave him the use of a couple of hundred horsemen, in return for allowing him to act as the vassal of Hungary. In early 1476 Corvinus, together with the Serbian leader Vuk Grgurević, led a campaign in Bosnia against the Ottomans, and Vlad was one of their leaders. Vlad’s men captured and destroyed many strongholds, including Srebrenica, Kušlat, and Zvornik.

The Serbian hvalno-pohvalni spomen, a popular work by a wandering Serbian minstrel, stated that in their campaign, Vlad’s men “slaughtered great numbers of Turks, hanged and impaled others; they took, burned and looted many cities and markets, leaving behind only ashes and stench.” This was not a great campaign, but the massacres and impalements were enough to recall Vlad’s earlier methods in Wallachia.

That summer, Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II invaded Moldavia and defeated Stephen III of Moldavia at Valea Albă. Stephen Báthory and Stephen III of Moldavia responded by leading their forces into Moldavia, with Vlad following them. Mehmed was forced to lift his siege of Târgu Neamț. Christian forces scored a short-term victory against the Ottomans, and by autumn 1476, preparations were already underway to invade Wallachia. Matthias Corvinus ordered the Transylvanian Saxons to join the invasion, and Stephen III of Moldavia advanced from the north. Vlad confirmed trade privileges to the merchants of Brașov as he prepared to reclaim his throne.

In November, the Christian army captured Târgoviște, then Bucharest, and drove Basarab Laiotă, Ottoman-backed ruler of Wallachia, into exile. Vlad Țepeș was crowned prince again before the end of the month. The coalition forces were not to have long in Wallachia, however. Basarab Laiotă returned with Ottoman support and attempted to reclaim the throne.

In late December 1476 or early January 1477 Vlad Țepeș died in battle against Basarab Laiotă’s army near Snagov. He was outnumbered and surrounded. The chronicles are vague on this event: one version claims a Turkish assassin killed him, the other that his own men accidentally killed him during the battle, as he was known to wear Turkish clothes during his campaigns. The manner of his death has never been verified.

It is thought that when he died, his body was dismembered, and his head was sent to Mehmed II. The sultan had Vlad Tepes’s head impaled and put on display on a stake in Constantinople to prove to his subjects that the Wallachian ruler was dead. According to peasant lore at the Snagov Monastery, the monks discovered and buried the remains. Excavations were made in the monastery’s cemetery in the 20th century to search for the remains of Vlad III, but no trace of the body was found.

Some historians believe that Vlad Țepeș is actually buried at the Comana Monastery, a church he built himself and which is close to the battlefield where he died. This theory, put forward by Constantin Rezachevici, is the one most historians believe to be true.

Terror with a Purpose

Vlad Tepes remains a figure suspended between infamy and admiration. Was he a madman consumed by cruelty, or a mastermind who used terror to defend his homeland? The answer may lie somewhere in between. His cruelty was undeniable, but it served a strategic purpose—to instill fear so powerful that even the mighty Ottomans hesitated. Reports of forests being impaled were not just acts of madness, but warnings: Wallachia would not submit easily. In a world ruled by brute power, fear was a language understood by all.

Vlad’s legacy endures not solely because of impalement but because of his ability to defy an empire through psychological warfare. He did not merely punish enemies—he made examples of them. His methods were harsh, but the times were equally harsh. Whether hailed as a hero or feared as a monster, Vlad Tepes proved that terror, when used with precision, could serve as a shield. In resisting one of the greatest empires of his era, he carved out a place in history not just for brutality—but for brilliance.