Why the St. Brice’s Day Massacre Still Haunts English History

The St. Brice’s Day Massacre of the Danes in 1002 was one of the most shocking moments in early English history. On a single day, by the king’s command, Danish men and women were massacred in every corner of his realm. It was sudden, unexpected, and horrified the men and women who heard about it. Royal charters surviving from the time tell us that the Danes were killed because they were plotting to overthrow the king and his councillors. Historians doubt this, but either way, it’s likely that the bloodshed that began on November 13, 1002, quickly got out of control, devastating towns across England and unleashing forces which would have consequences for years to come.

The massacre of 1002 was not a chance act; it was part of a pattern. For several decades, England had been under pressure from Viking raids, an uncertain government, and anxieties about the presence of foreign settlers. Danish men and women were to be found in many towns across the country. Some were merchants, some were families, some had lived in England for a generation or more, and might have been Viking warriors who had made their peace with the English.

Killing them was easy for the king to command, but much harder for his men to carry out. The massacre was a decision that would have enormous consequences for Æthelred’s reign, stirring up his enemies in Scandinavia and setting the stage for the conquest of England by Sweyn Forkbeard and Cnut the Great. The St. Brice’s Day massacre of 1002 remains part of English history because it shows how easily mistrust, fear, and political desperation can tip a nation onto a new path.

England Before the Massacre: A Kingdom Under Pressure

The years leading up to the St. Brice’s Day Massacre were characterized by increasing pressure from the Vikings. English shores had first been subject to raids from Scandinavian pirates in the late 8th century, but attacks during the 10th and early 11th centuries became more frequent, more organized, and more brutal. The English kings frequently resorted to paying off the raiders with large sums of silver, a practice called Danegeld, to avoid destruction and buy a few years of peace. Unfortunately, this only made further attacks more likely.

At the same time as these raids were taking place, large numbers of Danes had settled in England. The Danelaw was a large area of eastern and northern England where Scandinavian law, customs, and language became dominant from the 9th century, and many people living there or in other parts of England still had family and cultural connections with Denmark and other Scandinavian countries.

The existence of the Danelaw in England had mixed effects on English politics. On the one hand, many of the Danish settlers living in English territory had been under English rule for several generations and had adopted many English customs. On the other hand, many of these people retained their own leaders, customs, and languages. In some towns, the Danish community was large enough to make up a significant part of the population, and the two peoples did not mix easily.

To the mind of King Æthelred II and his councillors, this combination of settled Danes and new invaders created a significant degree of uncertainty: were these foreign raiders the enemies of the English king, or were his own subjects on the borders willing to cooperate with them? As the Viking armies swept across the land, the distinction between them became harder to see.

King Æthelred’s personal weaknesses further complicated matters. Æthelred was later vilified by chroniclers as “Æthelred the Unready”, whose name, when translated from Old English, ironically meant “ill-advised”. They believed that Æthelred had proved unable to consistently exert strong royal power over his kingdom.

Nobles were constantly squabbling for influence over the king, military plans were hastily changed or broken, and personal treachery seemed to characterise many of the nobility. In contrast to his predecessors, who had frequently fought and died to resist the Viking raids, Æthelred had opted for payments and treaties, which only seemed to make further attacks more likely. The strength of the English resistance was rapidly decreasing, and his own leadership came under increasing criticism.

The English government’s internal divisions hampered its response to these problems. The legacy of the Danelaw and its associated Danish settlements resulted in a split between regions with strong Scandinavian traditions and those without. Moreover, loyalties were not always clear, as Danish armies often returned to raid areas where Danish-descended families lived, raising questions about whether these families could be trusted. The nobility had their own internal rivalries, leading to shifting alliances from one year to the next. In many cases, it was even left to local lords to make their own deals with the raiders, further reducing the sense of national unity.

Out of these political and cultural divisions, paranoia began to increase at Æthelred’s court. Rumors spread that Danish settlers in England might rise and support any future Viking invasions, creating a hostile, coordinated front on England’s borders. A royal charter issued in the aftermath of the massacre stated that the Danes living in England had been “seeking to destroy the king and his councillors”, suggesting that the government genuinely believed that there was a conspiracy afoot. Modern historians have debated whether this statement was true, but the fact that it was made shows the level of fear the government felt at the time.

The English government’s diplomatic relations with Scandinavian rulers also increased the sense of pressure. Sweyn Forkbeard, the king of Denmark, had launched increasingly large-scale attacks against English towns and cities over the previous years. These attacks had been met with counterattacks and payments, but haphazardly, and each time Sweyn had returned with a larger army and more confidence.

The repeated attacks increased the tension between the English government and the Danish-descended population of the Danelaw. As what had seemed like an unstoppable threat loomed over the kingdom, Æthelred began to view the thousands of Danes in his kingdom as a potential fifth column. It was in this climate of fear, distrust, and political weakness that the decision to carry out the killings of November 13 was made, a decision that would reverberate across England for many years to come.

The Events of St. Brice’s Day, 1002

The St. Brice’s Day Massacre began with a written order. On November 13, 1002, the English king Æthelred issued a writ (royal decree) instructing his officials to kill all Danes in certain parts of the country. The original document is lost, but a later royal charter states the grounds for the order: the Danes “plotted against his life and his councillors.” The words are revealing. As well as Æthelred’s evident fear, they give a political explanation for later audiences, a kind of rationalisation of the event.

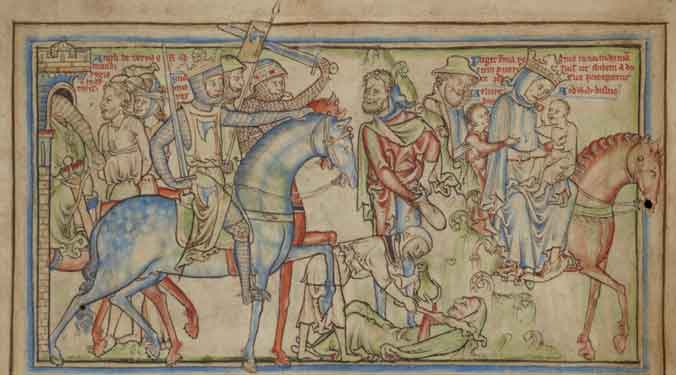

It is important to emphasise that this was not an order to fight: on St. Brice’s Day, 1002, mass killings took place in several different regions, coordinated over a period of days or weeks. They were not a response to an invasion force but to an internal population.

The victims were a diverse group. They included traders who had long-established communities in outport towns along the great rivers; craftsmen who worked in English towns; whole families who had lived for decades as part of the English community; and political hostages held by the king as an assertion of power. The most famous victim, named in later accounts, was Gunhilde, identified by some medieval writers as the sister of Sweyn Forkbeard, the king of Denmark.

The story cannot be proved, but medieval chroniclers were in no doubt that Sweyn was outraged by her death, and that the massacre shaped his invasion plans and campaigns. Whether or not the story is true, it is a potent symbol of the event’s violence and its political impact.

The people killed were not soldiers or raiders. The English of 1002 had long experience dealing with raiding parties and even with Danish settlers, and the Danes themselves often intermarried and adopted English language and customs while remaining loyal to their own leaders. On St. Brice’s Day, these differences made little difference. Some towns seem to have carried out the order, apparently with speed and violence. Others appear to have done so more reluctantly or, in some cases, to have refused it entirely. This varied response tells us as much about the complexity of English society in regions where the Danelaw had long ago ceased to exist.

Archaeologists have identified the sites of several killings from this period. In Oxford, the excavation of a college car park at St. John’s College in 2019 turned up a mass grave of human remains, which seem to be the victims of the massacre. The bodies, all young Danish men, appear to have taken shelter in a church and been burned alive after the townsfolk set fire to the building; they show signs of being stabbed and mutilated. DNA analysis of the bones suggests a Scandinavian origin, providing physical corroboration of the written sources for this location; other sites from the same period are known, although their exact locations are not yet certain.

The different response of communities along Æthelred’s command also tells us something about regional political differences, in areas that were close to or far from the old Danelaw: the fewer killings in the north may be explained by the difficulty of separating English from Dane in that region, or by a reluctance to carry out the order. In Wessex and along the Thames, the evidence suggests a more decisive approach: towns acted either out of fear of royal retribution if they refused, or, perhaps, less equivocally because they were more opposed to Danes in their communities. The massacre was not a centrally coordinated national event, but a patchwork of local flare-ups given royal blessing.

The St. Brice’s Day massacre is, then, both a political act and a social catastrophe. It both exposed and exploited the fragile boundaries between coexistence and fear in a kingdom battered by decades of raiding, tribute payments, and cultural and economic mingling. The brutality of the event – and of its uneven advance across the country – is a large part of what makes it one of the most disturbing episodes in the history of early England.

Immediate Consequences: England Sets the Stage for Invasion

The St. Brice’s Day Massacre had an immediate and spectacular impact. Sweyn Forkbeard, the king of Denmark, used the killings as both a personal and political casus belli. Historians record that he was furious about the story of his sister’s death and determined to take revenge on King Æthelred. The purported murder of Gunhilde and the larger massacre provided a potent narrative. Viking armies subsequently ravaged England with renewed vigour, attacking with fire, plunder, and methodical terror.

The invasions continued, and England’s tenuous defences were soon overwhelmed. The country had long since been paying off Danegeld, or tribute, to keep its southern shores relatively free of marauding Viking armies. The massacre put an end to this. Sweyn’s forces ransacked towns along the coast and soon moved inland. The raids were sustained and had the character of a military invasion rather than piracy. English efforts at resistance were met with crushing defeat. The kingdom’s internal divisions and an increasingly erratic king now appeared as glaring weaknesses. Each fresh humiliation further sapped the country of it’s will to fight.

By 1013, things had reached a crisis point. Sweyn successfully invaded and overran the kingdom with startling rapidity. Many English nobles, at this point jaded by Æthelred and no doubt with a memory of Sweyn’s previous dalliance as King of England, opted to submit to the Danish king rather than continue to fight a losing war. Sweyn’s army marched north even as King Æthelred, facing domestic failure and military defeat, fled the country. The king abandoned England for Normandy, taking his family and court with him, an act that effectively marked the end of his reign. It remains one of the most ignominious episodes in English royal history.

Sweyn Forkbeard died shortly after crowning himself King of England, but he had set in train significant political changes. His son, Cnut the Great, returned to England in 1015 and, by 1016, was crowned king, founding a dynasty that would last for almost three decades.

England would enjoy a degree of relative stability under Cnut, but of a kind very different from before. The new king’s rule marked a dramatic change of direction for the English monarchy, even as his reign would help lay the foundations for the future Angevin conquest.

The St. Brice’s Day Massacre played a vital role in this. It was not just the immediate Scandinavian reaction that was important, but the longer-term implications. The massacre altered the strategic context of northern Europe. England’s internal paranoia and external provocations mutually reinforced each other. The combined effect was to debilitate the English monarchy and to open the way for Scandinavian rule. The massacre of 1002, intended to secure and protect the English kingdom, ultimately hastened the fall of the Anglo-Saxon polity. In this sense, the killings remain important for English history, a turning point that offers a dramatic example of the costs of short-sighted and fear-driven policies.

Long-Term Effects on English Identity

In the following centuries, the St. Brice’s Day Massacre became part of the English cultural memory of traumatic events. Medieval chroniclers, including the authors of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, presented the massacre as a time of panic, repentance, and prophecy. They wrote of the massacre as if it had disrupted the nation’s sense of justice and guilt, and had been a foreshadowing of the kingdom’s doom. To some, the massacre was an example of what an autocratic monarchy might do in a panic, and it remained part of a cautionary narrative for later centuries.

The massacre also became part of King Æthelred II’s posthumous reputation. While he was not given the epithet “Æthelred the Unready” for several centuries, he was seen as a monarch who had lost control of his kingdom and failed to understand the consequences of his own actions. The massacre was a central reference point for historians, poets, and other storytellers seeking evidence of his ineptitude, and they used it to argue that a more effective monarch would not have stooped to indiscriminate violence or started a reprisal so vast as that of Sweyn. Gradually, the massacre became a primary reference point for interpreting Æthelred’s reign as an age of chaos.

The killings also had consequences for Anglo-Danish relations in the generations that followed. For many decades, the St. Brice’s Day Massacre contributed to a hardening of ethnic and cultural divisions, and it fixed ideas about English communities and people of Scandinavian origin that would last for generations. The massacre was framed as an act of betrayal for some, and an act of justified vengeance for others. In the generations after 1002, the event could be seen and heard in local folklore, in laws and legal practices, and in the sermons of local clerics.

Ironically, these consequences for Anglo-Danish relations were affected by the later reign of Cnut the Great. Relations between the two cultures improved as Cnut’s regime stabilized, and a new mixed Anglo-Danish identity was developed that fully assimilated Scandinavian military and political customs and cultural influences. At the same time, the contrast between the 1002 massacre and Cnut’s era, in which the two cultures coexisted more harmoniously, may have made the killings seem all the more pointless. A relationship based on trade, settlement, and occasional hostility had been disrupted by one order from one king.

The long-term consequences of St. Brice’s Day can also be felt today in how the English view their early medieval history. It is seen as a moment in which fear overwhelmed reason, in which political hysteria informed national action, and in which the results of those actions were felt for decades after the crisis that had caused them. The massacre is not only remembered as having left wounds on the land, but as having marked the identity of a kingdom in crisis, looking for ways to define itself against the foreign threat.

Archaeology and Historical Reassessment of the St. Brice’s Day Massacre

Archaeological investigations have recently shed new light on the St. Brice’s Day Massacre. The most significant breakthrough was the discovery of a mass grave at St. John’s College in Oxford in 2008, which we previously mentioned. The skeletal remains of 37 men, most of them in their 20s or 30s, displayed cut marks, broken bones, and signs of burning. Carbon dating put the time of death within the possible range of the year 1002, and forensic analysis of the skeletons’ injuries suggested that they had been killed by severe trauma. These findings support the description of the massacre in the early chronicles.

The Oxford excavations have provided an opportunity to examine the massacre in a forensic light. According to the archaeological team, many of the victims had been from Scandinavia, as determined by isotopic analysis of their teeth. This finding supports the theory that the massacre was primarily against men and that it had targeted Danish settlers. Furthermore, several skeletons had defensive wounds on their hands and arms, suggesting they had tried to fight back or escape. Other skeletons had been burned after death, consistent with some buildings being set on fire to flush out Danish residents. The archaeological evidence has transformed the massacre from a textual enigma into a violent, concrete event.

In light of the archaeological evidence, some historians have reinterpreted the massacre as an example of ethnic cleansing, or one of the first occurrences of such a phenomenon in England. The argument for ethnic cleansing centers on the indiscriminate nature of the royal edict and the presence of Danish settlers in multiple shires. The archaeological discovery of the mass graves has added to this interpretation by providing physical evidence of the scale of the killings. Others, however, argue that medieval chroniclers often inflated numbers and were prone to dramatic characterizations. They suggest that the killings were more politically selective and aimed at local rivals than a full-scale extermination.

The extent and scale of the St. Brice’s Day Massacre have also been subject to renewed debate. Medieval chronicles often provided approximate numbers and vague descriptions of the events, and some areas seem to have left no archaeological record of killings. Furthermore, some historians point to the logistical difficulties of organizing a massacre across several shires to suggest that the number of victims may have been exaggerated. The challenge remains in reconciling incomplete and often imprecise written records with limited material evidence. However, the discovery of mass graves suggests that the massacre was not symbolic or limited in scope but was a bloody event that affected many communities.

As part of the historical reassessment of the St. Brice’s Day Massacre, some historians have also sought to reevaluate Æthelred II’s legacy. In this view, the king did not issue the edict out of malice or paranoia, but as an attempt to avert what he saw as an imminent Danish rebellion.

Instead of being a tyrannical ruler, the massacre would have been a strategically motivated, if ultimately misguided, attempt to reassert control in a time of great insecurity. Others, however, see the massacre as a grave error in judgment, an event that alienated loyal settlers, invited savage retribution, and accelerated the end of Anglo-Saxon rule in England.

The archaeological discoveries and new lines of scholarly inquiry into the St. Brice’s Day Massacre are ongoing. As more evidence comes to light and new interpretations emerge, the understanding of this event in English history continues to evolve. It is clear, however, that what was once a barely-known footnote has now emerged as a pivotal episode. One that reveals not only the inherent risks of fear-driven governance but also the precarity of medieval polities and the long-term effects of state-sanctioned violence.

Why the St. Brice’s Day Massacre Still Haunts English History

The St. Brice’s Day Massacre endures in English historical consciousness due to its dramatic nature, its reflection of deep-seated issues, and its subsequent portrayal in various cultural and historical narratives. Æthelred’s actions, driven by fear and perceived need for decisive action, underscore the potential for panic and rash decisions to drive policy at the highest levels. By acting on impulse rather than through careful deliberation, Æthelred not only demonstrated the flaws and vulnerabilities of his rule but also provided a stark example of how easily the social contract could be violated, with long-lasting repercussions for governance and societal stability.

The massacre also brings to light the persistent themes of multicultural tension and the treatment of minority groups within a broader society. The relatively peaceful coexistence of Anglo-Saxons and Danes in the English towns and villages before the edict of 1002 was abruptly disrupted. The order to kill Danes upended the lives of those who had settled in England, contributing to its economy and culture. This aspect of the massacre is frequently discussed in the context of broader historical and contemporary issues, as it highlights the fragility of tolerance and the speed with which an entire ethnic group can be turned into scapegoats by political machinations and societal fears.

The narrative of the St. Brice’s Day Massacre has been perpetuated and kept alive through its inclusion in English literature, chronicling, and historiography. Chroniclers of the time, such as William of Malmesbury, depicted the massacre as a moment of divine retribution and a reflection of the king’s folly, which helped shape its perception in the immediate aftermath. In the centuries that followed, the event was referenced in historical novels, academic works, and eventually television documentaries as a representation of the era’s volatility. It has also been a subject of interest in the study of medieval governance and Viking history, ensuring that it remains part of the educational and cultural discourse.

The continued relevance of the massacre is also due to its thematic resonance with current events. Discussions around the treatment of ethnic minorities, the rhetoric of fear in politics, and the responsibility of leadership often echo the circumstances surrounding St. Brice’s Day. By serving as a historical parallel, the event encourages reflection on modern issues, thereby remaining pertinent and of interest to both historians and the general public.

The enduring interest in the St. Brice’s Day Massacre reflects its complex legacy as both a historical atrocity and a turning point in English history. It forces a reevaluation of the romanticized view of early medieval England and serves as a reminder of the consequences of decisions made in fear. The massacre is a testament to the intricate tapestry of Anglo-Saxon and Danish influences that would eventually shape the English nation. By continuing to study and discuss the event, modern audiences keep its memory alive, ensuring that its lessons are not forgotten and that the past continues to inform the present.