William Adams: The Real-Life Anjin Behind ‘Shogun

William Adams, the real-life Anjin, was the primary inspiration for the character in the epic novel and television series ‘Shogun.’ As the first Englishman to reach Japan, his extraordinary journey from a humble seafarer to a respected samurai under the Tokugawa shogunate encapsulates a unique chapter in the annals of cultural exchange.

Stranded in Japan in 1600 after a perilous voyage, Adams navigated the complexities of Japanese society at a time when foreigners were rare and often viewed with suspicion. His ability to adapt and thrive in a vastly different culture transformed his life and left a lasting impact on Japanese history and Anglo-Japanese relations.

Early Life of William Adams: Foundations of a Navigator

William Adams was born in the small town of Gillingham, Kent, England, in 1564. His childhood was marked by tragedy as he lost his father when he was just twelve years old. This pivotal event led him to an apprenticeship with Master Nicholas Diggins at Limehouse, a critical moment that would set the course for his future.

During this period, Adams dedicated himself to mastering the arts of shipbuilding, astronomy, and navigation. His apprenticeship prepared him for life at sea and instilled in him the rigorous discipline required for the adventures that lay ahead.

Launch of English fireships against the Spanish Armada, 7 August 1588

/ National Maritime Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

After his apprenticeship, William Adams entered the Royal Navy, where he served under the renowned Sir Francis Drake. His naval career included active participation in the defense against the Spanish Armada in 1588, where he served as master of the Richard Dyffylde, a ship tasked with resupplying the English fleet. Following his naval service, Adams became a pilot for the Barbary Company.

During this time, Jesuit sources attribute to him an expedition to the Arctic in search of a Northeast Passage, though this claim is contested and not mentioned in Adams’ writings. His extensive experience and the skills he honed throughout these years would later prove invaluable when he embarked on his historic voyage to Japan.

Perilous Journey: The Ordeal Before Reaching the Pacific

When William Adams, then 34, embarked on a daring expedition to the Far East in 1598, he was driven by the lucrative Dutch trade opportunities with India and beyond. Accompanied by his brother Thomas, Adams joined a fleet of five ships organized by a Rotterdam merchant company, aiming to exploit the riches of Chile, Peru, and other parts of New Spain.

This formidable fleet, a precursor to the Dutch East India Company, set sail with a daunting mission: navigate the treacherous Strait of Magellan to the west coast of South America, then move on to Japan if the initial plan faltered.

The voyage was fraught with challenges from the start. After departing from the isle of Texel, the fleet endured lengthy delays and soon faced dire shortages of provisions. To replenish their supplies, they anchored off the coast of North Africa, where Simon de Cordes, one of the expedition leaders, was forced to implement strict rationing.

The scarcity of fresh water and fruit drove them to the Cape Verde Islands, but their efforts to secure supplies there led to disease outbreaks among the crew, including the death of their admiral, Jacques Mahu. This early adversity set a grim tone for the journey ahead.

As the fleet ventured further into the southern hemisphere, their situation grew increasingly difficult. They navigated with inaccurate charts and faced relentless adverse weather, which pushed them off course to Cape Lopez in Gabon. Here, a desperate stop on Annobón Island resulted in further calamity as many crew members fell victim to dysentery and scurvy.

The sailors’ desperation reached a point where some resorted to eating leather to stave off starvation. Despite these hardships, the fleet pressed on, reaching the Rio de la Plata and finally approaching the dreaded Strait of Magellan, where their ordeal would continue amidst icy waters and hostile conditions, culminating in the loss of about two hundred men before ever seeing the Pacific.

From the Pacific to Japan: The Final Leg of William Adams’ Odyssey

William Adams and his fleet faced new challenges after surviving the treacherous Strait of Magellan and finally entering the Pacific Ocean on September 3, 1599. A severe storm soon struck, scattering the ships. The Trouw and the Geloof were pushed back into the strait. At the same time, the Geloof eventually made a harrowing return to Rotterdam in July 1600, carrying just 36 survivors from its original crew of 109. This dramatic reduction in their numbers was a stark testament to the journey’s brutality.

The expedition’s fragmented fleet attempted to regroup on Santa María Island, Chile, as ordered by Simon de Cordes, but failed coordination led some ships to miss the rendezvous. The islands offered some respite, providing the sailors with sheep and potatoes, but the relief was short-lived. In early November, tragedy struck at Mocha Island, where native Araucanians killed de Cordes and 26 others. The Liefde, now carrying Adams, encountered difficulties but managed to escape to Punta Lavapié near Concepción, Chile, where they engaged in a skirmish alongside a Spanish captain against the Araucans.

Amidst these continuous hardships and changes in leadership, Adams found himself aboard the Liefde, which had dramatically changed course for Japan. By November 1599, fearing further encounters with the Spanish, the remaining ships decided to cross the vast Pacific. Their journey was difficult, and they possibly made brief landfalls on uncharted islands, where several sailors chose to desert. By late February 1600, the Liefde was alone; the Hoope was lost to a typhoon, taking all hands with it.

This final leg of their journey was as dangerous as before, marked by uncertainty and the relentless threat of the sea. Yet, this part of the voyage would lead Adams to his unprecedented role in Japan, transforming him from a beleaguered navigator to an influential foreign samurai. The arrival of the Liefde in Japan marked the beginning of a new and unexpected chapter in Adams’ life, forever intertwining his fate with this distant land.

Arrival in Japan: William Adams and the Liefde’s Fateful Landing

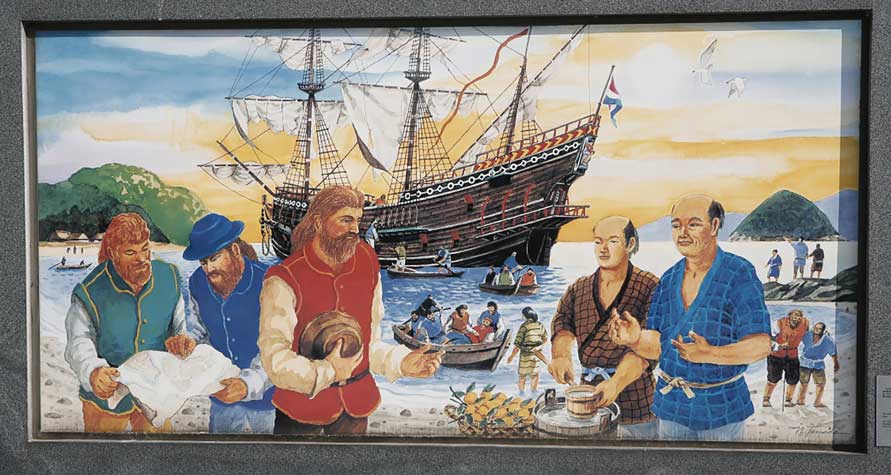

On April 19, 1600, after enduring a grueling 19-month journey, the battered ship Liefde, carrying a mere 23 of the original 100 crew members, anchored off the coast of Kyushu, Japan. The survivors were in dire condition, plagued by sickness and exhaustion. Among their cargo were trade goods like woolen cloth, glass beads, and spectacles, alongside a formidable arsenal of iron tools, bronze cannons, cannonballs, muskets, and chain-shot. This eclectic mix of merchandise was intended for trade but also served as a testament to their harrowing voyage across unknown seas.

Upon making landfall at Bungo (now Usuki in Ōita Prefecture), the crew was initially received with cautious hospitality. The local lord, Otomo Yoshimune, provided for their needs while awaited interrogation by Japan’s Council of Five Elders. However, the situation quickly deteriorated when Portuguese Jesuit priests, serving as interpreters, accused the crew of piracy and urged their execution. This led to the crew’s harsh imprisonment under the authority of Ota Shigemasa, lord of Usuki Castle, marking a stark turn from their brief period of comfort.

Amid these tensions, William Adams and the ship’s merchant, Jan Joosten, were summoned to Osaka Castle by Tokugawa Ieyasu, the powerful daimyo and soon-to-be shogun. Over several meetings in May and June 1600, Adams impressed Ieyasu with his extensive knowledge of shipbuilding and navigation, communicating through the interpreter Suminokura Ryoi. Ieyasu’s interest in Adams’ skills and understanding of the wider world became evident, offering a glimpse of hope for the beleaguered crew.

During his interrogations, Adams engaged in a detailed discussion with Ieyasu, utilizing a world chart to explain his journey via the Strait of Magellan, which Ieyasu initially found unbelievable. Adams’ candid answers about his faith, his country’s conflicts with Spain and Portugal, and his reasons for venturing to Japan struck a chord with Ieyasu, who ultimately rejected the Jesuits’ calls for execution.

Adams’ ability to navigate this complex interaction saved his and his crew’s lives and paved the way for his unique role in Japanese history. This encounter highlighted the stark cultural and diplomatic divides Adams would continue to bridge during his time in Japan.

William Adams’ (The Anjin) Service to the Tokugawa Shogunate

William Adams’ remarkable journey from a stranded sailor to a trusted advisor in the Tokugawa shogunate is a testament to his adaptability and skill. After surviving the perilous voyage to Japan, Adams and his crew were initially imprisoned. However, their fortunes changed when Tokugawa Ieyasu, recognizing Adams’ potential usefulness, offered him and his crew their freedom in exchange for assistance in the looming civil war.

Adams’ knowledge of artillery and naval tactics quickly made him an asset. He trained Tokugawa’s troops to use the cannon from the Liefde and participated directly in key battles, including the pivotal Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, which secured Ieyasu’s control over Japan.

Following Tokugawa’s victory at Sekigahara, Adams was rewarded handsomely but was not allowed to leave Japan. Instead, Ieyasu saw greater value in retaining him as a permanent advisor. In 1603, Adams was granted a substantial estate in Edo, complete with a large house, housekeepers, and a generous allowance. His crew also benefited from regular stipends, solidifying their roles as technical advisors to the shogunate. The Anjin’s’ unique position was further enhanced when he piloted the first Spanish merchant ship into Edo Bay, facilitating Edo’s emergence as a significant trading port.

By late 1604, Tokugawa Ieyasu decreed that Adams would remain in Japan for life, a decision underscored by granting him the prestigious status of samurai in 1605. Adams’ transition from a foreign navigator to a samurai and a direct retainer of the shogun exemplified his complete integration into Japanese society. He was also given the title of hatamoto, highlighting his proximity to the shogunal power. Additionally, Adams was entrusted with a fief in Hemi, within present-day Yokosuka City, which included numerous servants and substantial land, reflecting his high standing and the trust bestowed upon him by Ieyasu.

Adams’ tenure in Japan was marked by his service to the shogunate and his personal adaptation to Japanese customs and practices. Despite his profound connection to England, Adams grew to respect and admire Japanese culture, praising its civility, justice, and religious devotion. His life in Japan illustrates a profound cultural immersion and adaptation journey, culminating in a legacy that bridged two vastly different worlds.

William “Anjin” Adams: Pioneering Navigator and Diplomat in Tokugawa Japan (1603-1611)

In late 1603, the deteriorated Liefde was dismantled under the supervision of William “Anjin” Adams and Jacob Quaeckernaeck, marking the end of the vessel’s navigational days but the beginning of Adams’s influential role in Japan. At Tokugawa Ieyasu’s behest the following year, Adams helped construct Japan’s first Western-style ship in Itō on the Izu Peninsula. This 80-ton vessel was instrumental in surveying the Japanese coast, and the success led to the commissioning of an even larger 120-ton ship the following year. Adams’s involvement showcased his naval expertise and ability to integrate Western technology into Japanese society.

By 1604, Adams had become a key intermediary in international trade relations. Ieyasu sent him and other key crew members of the Liefde on diplomatic missions to Southeast Asia to establish contact with the Dutch East India Company, aiming to break the Portuguese trade monopoly. Despite numerous challenges, the Dutch eventually arrived in Japan in 1609, establishing a trading post on Hirado Island. Adams’s negotiations, marked by his astute understanding of international trade dynamics, were pivotal in securing expansive trading rights for the Dutch. This significant alteration in Japan’s foreign trade landscape underscored the depth of Adams’s diplomatic skills and his influence on Japan’s global engagement.

Adams’s diplomatic skills were further demonstrated in 1609 when he assisted in the aftermath of the Spanish galleon San Francisco wreck on the shores of Onjuku. This incident led to friendly relations between Japan and New Spain. In 1610, the ship he helped build, the San Buena Ventura, was lent to the Spanish for their return voyage, symbolizing a new era of diplomatic relations facilitated by Adams. His increasing influence and the trust placed in him by Ieyasu were evident when he was invited to visit the shogun’s palace at his leisure.

Throughout these years, Adams also found himself at the center of religious and geopolitical intrigue. His staunch Protestant beliefs and close ties with the shogunate made him a significant figure in the political landscape of Japan, often at odds with the Catholic Jesuits.

By 1614, his influence, a testament to his political acumen and the trust placed in him by Ieyasu, contributed to the shogunate’s decision to expel Portuguese Jesuits from Japan and restrict the activities of Catholic missionaries. This decision, reflecting the deep-seated concerns about European intentions of political domination under the guise of religious conversion, underscored the weight of Adams’s political influence and his role in shaping Japan’s religious landscape.

Significant naval technology, diplomacy, and international trade achievements marked William Adams’s service from 1603 to 1611 under Tokugawa Ieyasu. He was vital in Japan’s engagement with the global community during the early 17th century. His legacy as a bridge between Japan and the West and as a trusted advisor to one of Japan’s most powerful shoguns highlights his unique and pivotal role in the history of this period.

William Adams: Bridging Continents and Cultures (1611-1617)

In 1611, amidst growing global trade networks, William Adams reached out to the English East India Company’s settlement in Banten, Indonesia, attempting to re-establish communication with his homeland and encourage English trade with Japan. His letter, carried by English sailor Thomas Hill, emphasized the lucrative opportunities Japan offered, contrasting it with the monopolistic practices of the Dutch. This action marked the beginning of direct English involvement in Japan, highlighted by the arrival of Captain John Saris in 1613 aboard the ship Clove.

Upon Saris’s arrival in Hirado, the Anjin, demonstrating his deep integration into Japanese culture, chose to reside with a local magistrate rather than his fellow Englishmen. This decision underlined his unique position in Japanese society, straddling the line between his English origins and adopted Japanese lifestyle. During this period, Adams was critical in securing a Red Seal permit from Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu, granting the English broad trading privileges across Japan. Despite plans to return to England, Adams opted to remain in Japan, taking up a significant role at the newly established English trading post in Hirado.

Adams’s engagement with global trade continued to expand in the following years. In 1614, he orchestrated a trade expedition to Siam aboard the Sea Adventure, aiming to bolster the financial state of the English factory with valuable goods like sappan wood and deer skins. Although the voyage faced challenges, including a typhoon and resistance from local authorities, it ultimately proved profitable and showcased Adams’s adeptness at navigating the complex trade networks of Asia.

Throughout this period, Williams “Anjin” Adams continued to leverage his unique position to influence Japanese foreign policy and trade. His efforts culminated in 1617 with a voyage aboard the Gift of God to Cochinchina, where he aimed to expand trade further. Upon his return, he secured new trading licenses from Shogun Hidetada, further solidifying his role as a pivotal figure in Japanese maritime trade.

William “Anjin” Adams’s activities from 1611 to 1617 highlight his transformation from a marooned sailor to a critical player in international diplomacy and trade. His deep integration into Japanese society and his efforts to connect Japan with global trade networks illustrate his significant impact during this transformative period in Japanese history.

By 1604, Adams had become a key intermediary in international trade relations. Ieyasu sent him and other key crew members of the Liefde on diplomatic missions to Southeast Asia to establish contact with the Dutch East India Company, aiming to break the Portuguese trade monopoly. Although hampered by various challenges, the Dutch eventually arrived in Japan in 1609, establishing a trading post on Hirado Island. Adams’s negotiations were crucial in securing expansive trading rights for the Dutch, significantly altering Japan’s foreign trade landscape.

The Anjin’s diplomatic skills were further demonstrated in 1609 when he assisted in the aftermath of the Spanish galleon San Francisco wreck on the shores of Onjuku. This incident led to the establishment of friendly relations between Japan and New Spain. In 1610, the ship he helped build, the San Buena Ventura, was lent to the Spanish for their return voyage, symbolizing a new era of diplomatic relations facilitated by Adams. His increasing influence and the trust placed in him by Ieyasu were evident when he was invited to visit the shogun’s palace at his leisure.

Throughout these years, Adams also found himself at the center of religious and geopolitical intrigue. His staunch Protestant beliefs and close ties with the shogunate made him a significant figure in the political landscape of Japan, often at odds with the Catholic Jesuits. By 1614, his influence contributed to the shogunate’s decision to expel Portuguese Jesuits from Japan and restrict the activities of Catholic missionaries, reflecting the deep-seated concerns about European intentions of political domination under the guise of religious conversion.

The Anjin’s service from 1603 to 1611 under Tokugawa Ieyasu was marked by significant achievements in naval technology, diplomacy, and international trade, making him a key figure in Japan’s engagement with the global community during the early 17th century. His legacy as a bridge between Japan and the West and as a trusted advisor to one of Japan’s most potent shoguns highlights his unique and pivotal role in the history of this period.

The Family, Death, and Enduring Legacy of William Adams

William “Anjin” Adams remembered as one of the first Englishmen to reach Japan, had a complex and bifurcated family life spanning two continents. Before his historic voyage, Adams married Mary Hyn in 1589 in England, with whom he had two children, John and Deliverance. His unintended permanent stay in Japan led Mary to face financial hardship, ultimately becoming destitute, though she later received some of Adams’s wages from the East India Company. Deliverance continued the family line in England; she married and had her own children.

In Japan, the Anjins formed a new family by marrying a Japanese woman, commonly believed to be named Oyuki, who was the adopted daughter of Magome Kageyu. They had two children, Joseph and Susanna. Adams’s integration into Japanese society was profound; he became deeply culturally and professionally embedded. Despite his significant roles and responsibilities in Japan, he maintained his connections with his English family, sending funds back home and making provisions for them in his will.

Adams died in 1620 in Hirado, leaving a considerable legacy and complex estate that included property and assets in Japan and England. His will stipulated that his assets be divided equally between his families in both countries. However, the transfer of his English family’s inheritance was delayed, and they only received it after his wife Mary’s death. Adams was buried in Hirado, and despite the initial destruction of foreign gravesites during periods of Christian persecution in Japan, his remains were later safeguarded and reinterred.

After his death, Adams’s son Joseph inherited the title of Miura Anjin and continued his father’s work, engaging in several trade voyages across Asia. The continuity of Adams’s influence through his children in Japan underscores the profound impact of his life and work there. Over time, the Anjin’s story has captured the imagination of many, influencing various cultural depictions and commemorations, from literature and television to video games, highlighting his unique role as a bridge between the East and West during a pivotal era in global history.

This was helpful in understanding some of Adams’ history but FYI the paragraphs repeat toward the end. Error.