George Washington’s Secret Weapon: The Culper Spy Ring

The Culper Spy Ring was one of the most closely guarded secrets during the American Revolution. Formed by General George Washington, the spies were based in New York and Long Island when the country’s future was still undecided.

A select group was well-versed in espionage, and their work was vital in the fight for independence. Their work was unknown to the public during the war, but we do know a bit about them.

The Foundations of Espionage in the American Revolution

The significance of intelligence in the early years of the American Revolution was demonstrated by the difficulties encountered by George Washington. In the initial phases of intelligence, information gathering was more haphazard and unstructured, based on bits of information from a wide range of sources, such as Lawrence Mascoll.

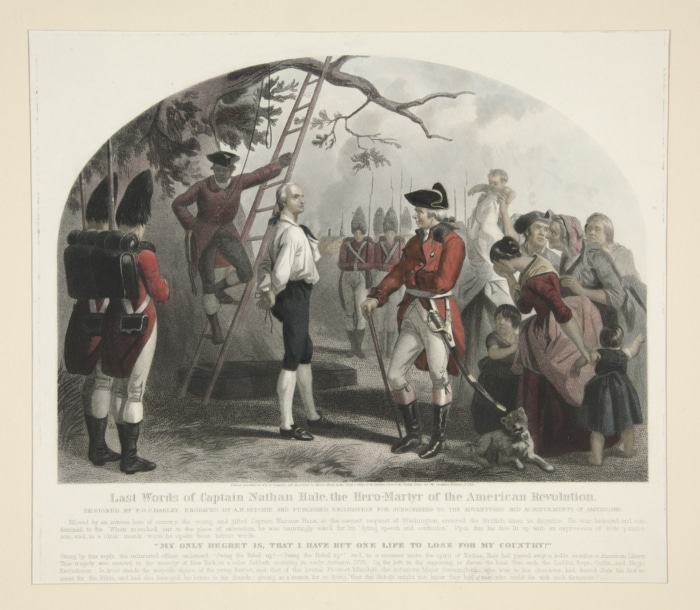

Early efforts were more tenuous, and in some cases futile, as was the case of Captain Nathan Hale, who was captured and hanged by the British in 1776, while on a mission to spy on the British in New York City. Hale had crossed into the city disguised as a Dutch schoolteacher to ascertain the British strategy, and his death underscored the need for a more effective clandestine information system.

Washington, recognizing the need for a “channel of information,” asked William Heath and George Clinton to organize a regular system of espionage, as one did not yet exist. Intelligence gathering was sporadic and short-lived, clearly showing the dangers of such an endeavor and that military personnel were typically unsuited to this work.

The beginnings of an organized spy network can be attributed to William Duer, who proposed Nathaniel Sackett as an agent. Sackett’s early accomplishments, including uncovering British plans for an attack on Philadelphia using flat-bottomed boats, established the value of strategically placing sources. Washington sought a more efficient flow of intelligence with greater accuracy, eventually leading to Sackett’s dismissal and the pursuit of more effective operatives.

This hunt for better information led to a series of networks, one of which was a system on Staten Island under the auspices of American Colonel Elias Dayton, which worked in conjunction with the Mersereau Ring. The shifting tide of the war and the occupation of Philadelphia in 1777, following the Battle of Brandywine, led to a renewed effort in intelligence gathering in the occupied city. Major John Clark was the man given this daunting task, but he was soon replaced because of illness.

These experiences in intelligence led Washington to place greater value on espionage during warfare and to develop a larger network, such as the Culper Spy Ring. Washington’s policies in this area changed throughout the war as he realized that espionage, in the form of well-organized, clandestine operations and civilian collectors, could be used to gain an edge over the British.

Foundation of the Culper Spy Ring: A Necessity for Revolutionary Intelligence

In 1778, George Washington faced a critical disadvantage: there was no unified intelligence service to coordinate information against the British. He was so in need of information that he welcomed a request from Lieutenant Caleb Brewster of the Continental Army for intelligence reports from Connecticut. The first ones provided intelligence of British ship movements before the Battle of Rhode Island.

The war’s evolving complexity and the need for more organized intelligence soon led Washington to charge General Charles Scott with managing Brewster’s efforts and recruiting a broader network. Major Benjamin Tallmadge, working under Scott, would prove key to this endeavor, effectively creating the Culper Spy Ring. Tallmadge saw the merit in a system of organized networks rather than relying on individual, short-term spies. He would suggest placing embedded agents in New York City to gather intelligence and maintain an effective, constant line of communication.

The first to be engaged was Abraham Woodhull, a childhood friend of Tallmadge’s from Setauket, Long Island. Washington recommended using the alias “Samuel Culper” for Woodhull. Woodhull began taking regular intelligence trips to New York City. This activity was supported by a complex communication system, including couriers such as Austin Roe, who carried messages along dangerous routes connecting the spies with Washington’s headquarters.

Operating with a blend of resourcefulness and caution, the spy ring’s activities often involved the use of ciphers and codes to safeguard the information they handled. One of their tactics reportedly involved using a black petticoat hung on Anna Strong’s clothesline in Setauket as a signal of Brewster’s location. These methods allowed for the relatively safe transfer of important information and demonstrated the adaptive strategies employed by the Culper Spy Ring.

Successes continued to be scored as the network expanded. Danger was always present—perhaps most so when Woodhull narrowly evaded a British checkpoint at night. Despite these perils, information of all kinds was being brought to Washington. Detailed dispatches concerning British troop movements, fortifications, and supply lines in New York were provided by Woodhull and Paulding, giving the Continental Army the kind of timely intelligence they needed in order to make strategic decisions that could shape the course of the Revolutionary War.

Expansion and Evolution of the Culper Spy Ring in 1779

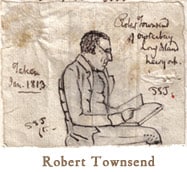

The growth of espionage kept pace with the intensity of the American Revolution. In June 1779, Abraham Woodhull, who was using the code name “Samuel Culper Sr.,” hired Robert Townsend, code name “Samuel Culper Jr.,” to provide intelligence in New York City. Townsend, who was running business operations in New York City as a cover for his spy work, could mingle with British officers as a tailor and wrote a society column for a Loyalist newspaper to get up close and personal with British gossip and plans.

Townsend’s occupation as a businessman and journalist, as well as his financial interest in a coffeehouse he ran with the newspaper’s owner, James Rivington, who was also a spy for the Culper Ring, enabled him to easily fit into British circles and gather information without arousing suspicion.

Townsend’s presence in New York changed the face of the Culper Ring. With Townsend in New York, Woodhull did not have to be there as well, reducing the likelihood that the spy network would be discovered and Woodhull arrested. The Culper Spy Ring’s intelligence communication system also became more effective.

Townsend would deliver information to a courier, first Jonas Hawkins, and later Austin Roe. The courier would provide the information to Woodhull, who would decipher it, make any recommendations or additions, and send it to Caleb Brewster, who would ferry the reports across the Long Island Sound to Benjamin Tallmadge, who would send it to George Washington.

The network, however, still experienced problems, including issues with its courier system. Jonas Hawkins, the original courier, became overwhelmed by the increased British patrols and started to fear the consequences of his role. The ring began to question his reliability in mid-1779 after Hawkins burned important correspondence rather than risk capture by the British. Tensions quickly rose between Hawkins and the other members of the spy ring, and Austin Roe became the main courier later that year. This change created a more secure, less noticeable connection between Townsend and the spy ring’s leadership.

The changes in Townsend’s operations in 1779 increased the effectiveness of the Culper Ring and established the spy network as an integral part of the war. By remaining in deep cover in New York City, Townsend’s work provided the Continental Army with reliable intelligence, giving the rebels the upper hand against the British. This shift in operations for the Culper Spy Ring demonstrated their ability to adapt to the changing nature of war and espionage, becoming a standard for intelligence operations today.

Intricate Operations of the Culper Spy Ring

Culper Spy Ring’s members used an elaborate code that ensured information was communicated successfully and, more importantly, safeguarded each member’s identity. Even George Washington did not know the identities of some agents. Robert Townsend has been identified as a primary source of information to Washington, but Townsend, like most other spies, used an alias. Townsend specifically asked that those he met regularly who gathered information and transferred funds to the Culper network not disclose his true identity to anyone else.

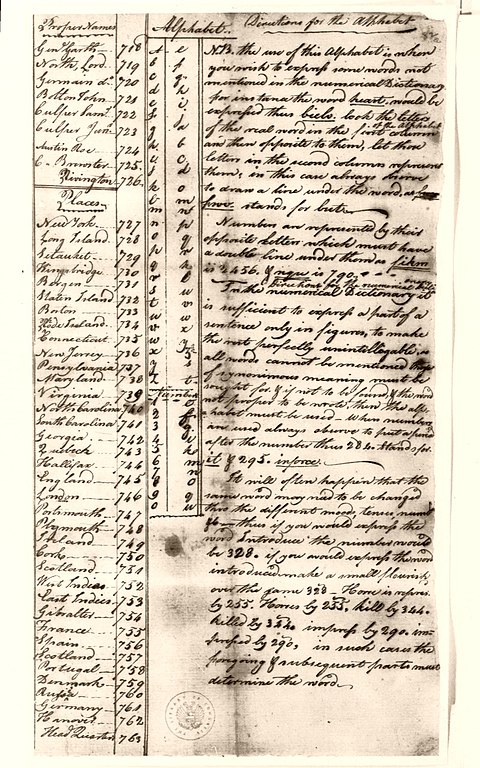

Communication was a creative challenge. At first, they embedded coded information into innocuous messages that appeared in newspapers or were written in invisible ink, or “sympathetic stain”. These ordinary-looking messages were replete with strategic information about the locations and plans of British troops. The ring initially used a small number of memorized codes. They used numbers for places and some important people to hide key information if an agent were captured.

As the war continued, Benjamin Tallmadge, the ring’s quartermaster, saw that they needed to improve their system. In 1779, he devised a codebook that greatly expanded the ring’s coded vocabulary. The codebook included lists of verbs, nouns, and people and place code numbers that the spies used to construct coded messages that were increasingly difficult for outsiders to decode. Ring members, including Washington, were also assigned code numbers for additional anonymity and security in communications. Washington’s code number was 711.

The Culper Ring’s methods marked an evolution in spycraft. Where earlier efforts like Nathan Hale’s had been unsophisticated, their operations, with invisible ink and a codebook, showed impressive innovation for the time. The information they relayed to Washington helped the war effort, and their tactics advanced the field, setting precedents for future espionage.

Expanding the Network: Associates of the Culper Spy Ring

The Culper Spy Ring was also made more effective by other people who did not serve as a primary member of the ring. In New York, James Rivington owned and published a newspaper that served as a significant source of information. Rivington, who was also a primary member of the spy ring, was a known Loyalist, though his involvement as a spy was kept secret by most of the patriots. Rivington would often provide information to Washington, often by publishing it in his newspaper as news or in the society column.

In 1781, George Smith, whose codename was “S.G.”, became part of the ring. Smith, a Nissequogue resident, was the great-grandson of Smithtown’s founder. He took over Culper Jr.’s role as a field agent in the network and was chosen for his local ties and knowledge of the area, both of which would be helpful to the ring’s operations on Long Island. He was the first to acknowledge the existence of the Culver Spy Ring after the war. His role in the network was later detailed by local historian Virginia Eckels Malone, who brought his work to light.

Brothers Nathaniel and Phillip Roe also assisted, especially in areas north of Setauket and Oyster Bay. Nathaniel gave information, and Phillip provided material aid, to the spy ring.

Selah Strong, another essential figure but heretofore unrecognized, was similarly posthumously identified and credited for his role decades later. It was determined that his position and subsequent activities were vital to the movements and safety of Caleb Brewster’s whaleboat crew that carried critical dispatches across Long Island Sound and back. The uncovering of Strong’s involvement illustrates how historical narratives can change over time as new evidence emerges.

Unraveling the Enigma of Agent 355

Agent 355 was a code name given to a spy who was part of the Culper Spy Ring. She is one of the least known members of the spy ring, and her identity has been a source of debate among historians. Historical references indicate that 355 was an agent within this spy ring and, in the code, is credited with the most critical work on one of the ring’s most significant accomplishments: the revelation of Benedict Arnold’s treachery. Her true identity is still debated, and historians have speculated that she could have been a lady of high society, a servant, or a slave in the British encampment.

Whoever Agent 355 was, the continued speculation about her identity reminds us that women had certain advantages in the spy game during the Revolution. Rarely considered players in political or military affairs, women were able to see and hear without attracting much notice. Thus, while American and British commanders were otherwise occupied, women like Agent 355 were able to gather information that passed right under their noses. Indeed, her intelligence is thought by some to have led directly to the capture of Major John André, Arnold’s British contact.

Agent 355’s identity has been the subject of much speculation. Several have proposed that she was part of a Loyalist family or even a slave. This would have allowed her to overhear information about British plans and troop movements. Her usefulness as a spy to Washington was that she had access to information, but could not be identified.

Adding to the enigma, some sources claim that “355” may not have been an individual at all, but a generic code name for female agents in the spy ring. Given the lack of concrete information, this theory has also been the subject of much speculation. Regardless of whether Agent 355 was one person or represented many, her story symbolizes the critical, often unrecognized contributions of women to the revolutionary cause.

Culper Spy Ring’s Critical Alert Warning of Tryon’s Raid

One of the Culper Spy Ring’s most important pieces of intelligence was an advanced warning that British Major General William Tryon planned a raid in July 1779. The information allowed Washington to prepare for Tryon’s attack. The British plan, as communicated by the spy ring, was to divert Washington’s forces with Tryon’s raid. The diversions would then allow Lieutenant General Sir Henry Clinton to carry out a piecemeal attack on the Americans.

The timely departure of this spy ring helped Washington learn the true purpose of the British military and assisted him in neutralizing the threat as much as possible before Tryon’s raid. This early warning from the Culper Spy Ring allowed Washington to save his strength for more critical battles.

Strategic Insights: Thwarting British Plans in Rhode Island and the Currency Plot

The Culper Spy Ring was key to foiling British plans for military operations that would have changed the outcome of the American Revolution. The Culper ring learned about a plan for a surprise attack on the French forces of Lieutenant General Rochambeau in Newport, Rhode Island. The French had joined the American rebels in 1780, and Rochambeau’s troops were still suffering from their long, arduous voyage across the Atlantic.

The British wanted to exploit their weakness before the Americans recovered and presented a larger military threat. The information provided by the Culper Spy Ring enabled American reinforcements to arrive promptly and support the French troops, preventing a potentially crippling blow to the newly forged Franco-American alliance.

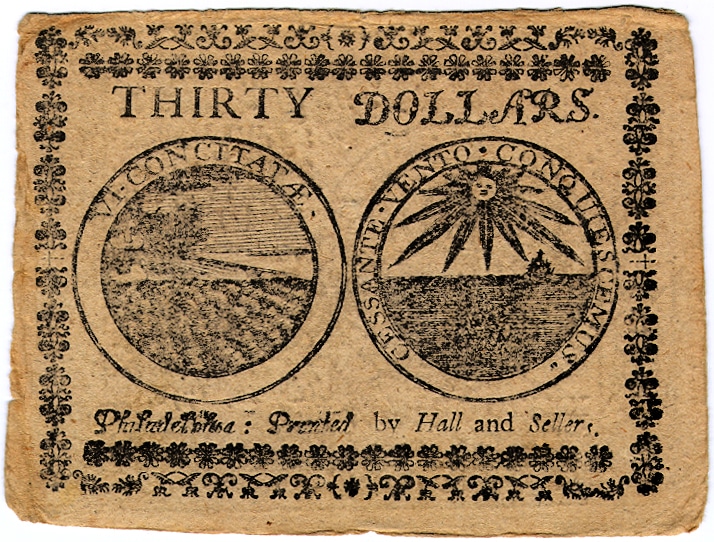

Furthermore, it uncovered a British economic warfare plot to cripple the American economy. The British hoped to hurt the American war effort by printing counterfeit Continental dollars. The British intended to drive the Colonial currency worthless by flooding the market with counterfeits. The ring also revealed that the counterfeit dollar operation was no small-time scheme of economic sabotage. The British planned to use the same stock paper as the Continental currency, making the fake bills indistinguishable from the real ones.

Armed with this intelligence, the American leadership is greatly concerned about the potential ramifications of the British counterfeiting operation. Recognizing the threat to the American economy and the war effort, the Continental Congress took action to implement new currency measures to stabilize the situation.

The Culper Spy Ring’s success in uncovering and thwarting the British counterfeiting operation had a profound impact on the war effort on multiple fronts. By preventing the enemy from gaining a foothold in the American financial system and jeopardizing crucial military supplies, the ring’s actions helped safeguard vital military alliances and maintain the economic viability of the American cause.

The disruption of the British counterfeiting operation marked a significant victory in the ongoing battle of wits and counterintelligence between the Culper Spy Ring and the British forces. It highlighted the critical importance of timely and accurate intelligence in protecting national security and shaping the outcome of the Revolutionary War.

Exposing Betrayal: The Culper Spy Ring and the Arnold-André Conspiracy

One of the most infamous betrayals in American history was foiled by the Culper Spy Ring. Benedict Arnold’s plan to betray West Point to the British in 1780 was thwarted by information from the spy ring. Arnold, who was a general in the Continental Army, planned to turn the fort over to the British in an attempt to strangle the rebellion. The spy ring became suspicious when they intercepted a letter from a high-ranking American officer addressed to the British Major John André.

The trail of evidence continued to grow stronger as the Culper Ring collected more solid proof with the help of its vast network. Agent 355, whose identity remains unknown, sent important information that also zeroed in on Arnold. The spies also infiltrated deep into the British and Loyalist communities. They received copies of letters from Arnold to André as they both plotted to lessen American strength and deliver West Point.

The ultimate success of the ring was when American forces captured John André just north of Tarrytown, New York, while he was dressed in civilian clothes and was trying to return to the British lines. Hidden in his boot were papers revealing the plot. When the documents were turned over to American officials, they clearly stated Arnold’s plot and the terms under which he had agreed to surrender the fort. The exposure of André and his plot also highlighted the role the Culper Spy Ring had played in protecting American interests.

Arnold, who had been warned of André’s capture in advance, was able to escape to a British ship. He ruined his reputation and career as one of America’s foremost military figures. John André was court-martialed and hanged as a spy, becoming a martyr to the British cause and a traitor to the Americans. American troops were now on high alert, and the morale of the Continental Army improved as the Culper Spy Ring eliminated a serious threat to the American cause.

On September 29, 1780, the tribunal found that André had unlawfully entered American territory under an assumed name and in disguise. The tribunal judged him to be the British Army’s Adjutant-General and declared that “as a spy” he should “suffer death, according to the law and usage of nations.” Sir Henry Clinton, who esteemed André as his aide-de-camp, tried desperately to spare him. During the course of their correspondence, however, George Washington demanded that the British trade André for Arnold, who was now safely in British hands in New York.

Clinton, who loathed Arnold, was not going to give him up. But André’s behavior from the time of his capture did earn him the respect of many Americans, including Alexander Hamilton. He was captivated by what he described as André’s “peculiar elegance of mind and manners, and the advantage of a pleasing person.” John Andre

On September 29, 1780, Major John André was convicted of the charge of having penetrated the American lines in a false name and in disguise by a board of officers. The board announced that “John André, Adjutant-General of the British Army, is adjudged a spy, and that as such, according to the law and usage of nations, from the evidence before us, he ought to suffer death.” Sir Henry Clinton, who was partial to André, used all his influence to obtain a reprieve.

In the meantime, Washington, in his negotiations with Clinton, made it a condition that André’s life should be given for Arnold, who was in British hands in New York. Clinton, although he hated Arnold, would not surrender him.

From his arrest onward, André came to the attention of many Americans. Some of them, such as Alexander Hamilton, came to bitterly regret their sentence, and Hamilton wrote of André as having “a gentle, polished, and captivating deportment, and an elegant, fluent mind.

On the eve of his execution, André petitioned for a soldier’s death by firing squad rather than a spy’s death by hanging. He wrote to Washington: “I trust that the request that I make to your Excellency at this serious period, and which is to soften my last moments, will not be rejected. Sympathy towards a soldier will surely induce your Excellency and a military tribunal to adapt the mode of my death to the feelings of a man of honor.”

Washington, however, refused to comply. André was hanged on October 2, 1780, in Tappan and was commended for his courage in the act of execution as he put the noose around his own neck. The day before he was executed, he sketched a self-portrait in pen and ink that is now in the possession of Yale College. A religious poem written by André two days before he was hanged was also discovered in his pocket. It is said that Lafayette wept when he saw André being hanged. Hamilton later wrote that “Never perhaps did any man suffer death with more justice, or deserve it less.”

Legacy of Shadows

The Culper Spy Ring is one of the most fascinating and significant American Revolutionary War espionage networks. The work of this intelligence gathering is an embodiment of General Washington’s strategies in George Washington’s intelligence network. Their secret activities and crucial contributions significantly shaped the war’s outcome, providing critical information that helped ensure American victory and independence. The unsung heroes of the Culper Spy Ring’s operations not only displayed extraordinary courage but also set a precedent for future intelligence operations, leaving an indelible mark on the art of espionage.

The profound impact of the Culper Spy Ring is a testament to the transformative power of information in shaping historical events. The legacy of their brave service and sacrifice reverberates through the annals of history, as their unwavering dedication to the cause of freedom played a crucial role in safeguarding a nation’s future. By exposing the weaknesses of the British forces, the Culper Spy Ring not only contributed to the success of the American Revolution but also redefined the role of intelligence in warfare, forever changing the course of history.