The 7 Biggest Impacts the Industrial Revolution had on the Working Class

The Industrial Revolution, which took place between the late 18th and early 19th centuries, was a period of massive economic and social change worldwide. The most visible change during this period was the shift from human or animal labor to mechanized production. New technological developments also began to influence how work was done. During this time in history, what was seen as work was redefined as factories began to replace smaller production models.

Mass production with the aid of machinery had become the norm, and the lives of ordinary workers changed accordingly. This period was seen by some historians as a breakthrough in the development of human culture, even as rapid economic growth brought noticeable changes in the lives of the working class. In this chapter, we will discuss the seven most significant ways the Industrial Revolution impacted the lives and reality of the working class.

Urbanization: The Rise of Industrial Cities on Both Sides of the Atlantic

The process of urbanization was, in many ways, inextricably linked with the changes of the Industrial Revolution. The expansion of factories brought a workforce, with migration from rural areas into newly industrialized cities becoming a dominant trend. This can be seen on both sides of the Atlantic in both the UK and the US. The major centers of this expansion in the UK were Manchester, known as “the Cottonopolis,” Liverpool, and Birmingham.

Likewise, in the US, the expansion of Pittsburgh’s steel industry and of Lowell, Massachusetts, and its textile mills attracted an industrial workforce to these cities. This process soon spread across most of the modernized world, with cities and industrial works springing up across many countries, and they soon became the dominant places of employment.

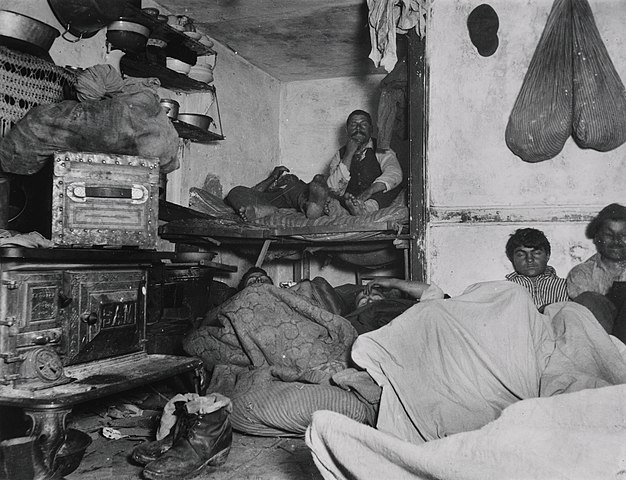

However, this brought with it its own host of problems. Cities often found themselves ill-equipped to handle sudden population demands and sometimes struggled to provide for the new workers. Overcrowding was a serious problem, with the poorest living in tenements where whole families shared a single room with other families on each floor. Sanitation was often inadequate, and could lead to health problems such as cholera in the poorer areas of the rapidly expanding cities of both the US and the UK.

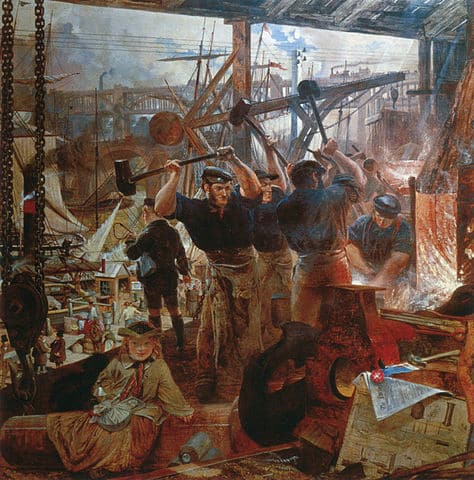

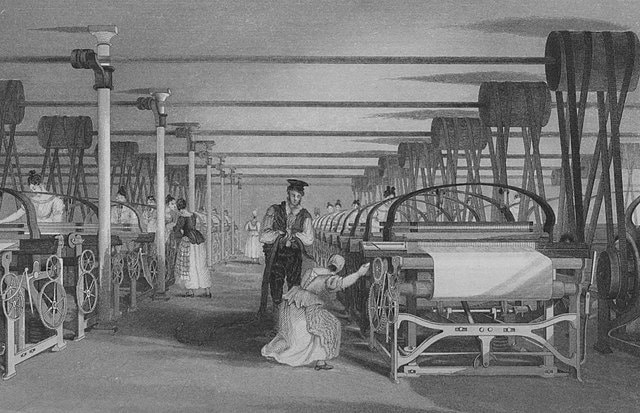

Working Conditions: Grueling Realities Inside the Factories

Before the Industrial Revolution, the concept of work was far different from what it would become afterward. In fact, for most of the working class, work involved the tasks and labor of an agrarian lifestyle, with its seasons and fluctuations in duties. When the Industrial Revolution began, however, people started working in factories, places where machines, steam, and the tick of the clock would rule.

Workers were confined to large rooms, forced to work as if part of a giant human machine. Not only were the workers required to perform the same tasks repeatedly, a straightforward action that was part of a larger production, but they also worked incredibly long hours. Instead of a 12-hour workday being considered terribly long, a 16-hour workday was common. Additionally, workers would have had to work while extremely tired, with little rest, due to the incessant need to keep production up.

Fatigue and monotony were only some of the difficulties of the working class. In the early Industrial Revolution, worker safety was a seemingly unimportant issue. Factories were dangerous places with belts, gears, and steam. It was easy to get caught in these and suffer a severe injury or death. This issue of safety, along with the grueling work many did, was a major part of a common refrain during the early Industrial Revolution: the outcry for better working conditions.

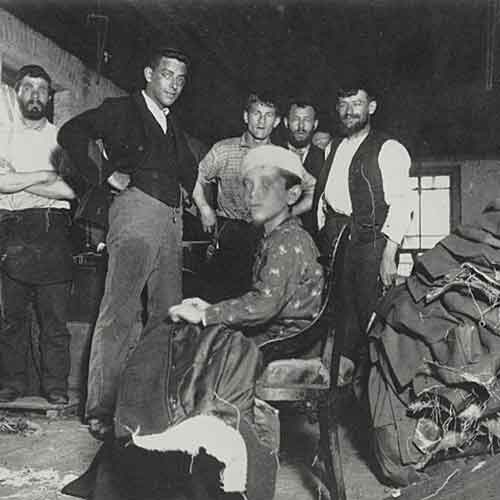

Child Labor during the Industrial Revolution

One of the most tragic aspects of this period was, however, the use of child labor. The sight of children working in the same factories as adults was common during this time, and the thought of small children, as young as toddlers, working in the harsh conditions of these factories is one of the most pitiful aspects of this period of industrial growth.

Children were assigned specific roles in these factories, and a significant factor in their assignment was their size. Their small size allowed them to change spools, correct minor machine malfunctions, and even crawl into small spaces where larger people could not fit. The only other reason for the use of child labor was the nature of children themselves at the time.

Children were not seen as important or as special as they are now; in fact, in some cases, they were actually seen as an annoyance. Children of the poor were no exception to this, so they were often sent to work at the factories. The factories were also quite willing to take advantage of this low-income labor for less than they would pay a normal worker.

However, this was not the only problem that occurred with child labor. The psychological and physical toll of such work on the young laborers was extensive. Children sent to work at these factories were forced to work long hours for long days, time that could have been spent having a childhood and learning. Furthermore, they were more likely to be hurt from both accidents and from the long-term health effects.

The Shift to Wage Labor: A Double-Edged Sword

Work and employment in the industrial era were distinctly different from those in the pre-industrial era. Before the Industrial Revolution, the majority of people were involved in subsistence agriculture, handicraft, or small-scale trade. In many cases, work was organized around family or community units, and people had direct access to and control over the means of production and the goods they produced. This type of work allowed individuals to have a clear sense of the purpose and outcome of their labor, as well as a direct impact on their economic well-being.

The Industrial Revolution brought about a fundamental change to the nature of work and employment. The rise of factories and the mass production of goods led to the growth of a new class of workers who sold their labor to factory owners in exchange for a fixed wage. This new mode of work was called wage labor or salaried work. The shift to wage labor changed the relationship between workers and the products of their labor. Instead of producing goods themselves, workers became part of a larger system of production and distribution, often with little or no connection to the final product. This could lead to a sense of alienation and disconnection from one’s work.

Additionally, dependence on wages made workers vulnerable to economic fluctuations. While a fixed wage could provide stability during times of prosperity, workers faced the risk of unemployment or wage cuts during times of economic downturns. Their livelihoods were at the mercy of factory owners and managers, who could close down operations or lay off workers at any time. In short, while the Industrial Revolution brought about economic growth and prosperity for many, it also created new challenges and uncertainties for the working class, who had to adapt to a new mode of work and employment.

The Rise of Labor Movements: A Quest for Dignity and Rights

Amid the rise and prosperity of the Industrial Revolution, factory owners and their kin reaped success from the large-scale production at their factories. At the same time, the working class in those settings suffered due to poor working conditions, low wages, and insufficient rest, which were all that workers received at the height of industrial progress. The unions and worker groups who were out fighting for their rights soon began to form based on what they were going through – a miserable life.

The experience workers had to undergo when employed at an industrial establishment was enough to spark labor movements. It is no exaggeration to mention that the unions that began during this age were acts of rebellion by the oppressed working-class society against the overfed factory owners and their cronies. They wanted to improve the industrial world so they would no longer be at the mercy of their employers in those workplaces. These unions in the industrial age fought for workers to have some rest from the overwhelming work schedule, to have at least some level of workplace safety and fairness, and to be paid a fair wage.

The workers who formed unions fought for the pay and conditions they deserved. The labor force, no matter the intensity of the strikes and go-slows they put forward, used them as attention-grabbing campaigns to make factory owners consider their needs.

There were victories on some accounts, but factory owners, in most cases, used their power to retaliate, figuratively and sometimes literally, beating the working class back down. They called in their private security details, and in some extreme cases, the state militia was made to deal with the protesting masses. The strikes and protests were put down; however, through all of this, the labor movement managed to make its voice heard, and many of its initial demands are rights that employers are now obliged to provide their workers.

Social Stratification: The Wealth Divide in the Era of the Industrial Revolution

Amidst the smoke and clamor of the Industrial Revolution, there lurked an unintended and oft-forgotten consequence: the widening chasm between the affluent and the destitute. As the gargantuan wheels of industry turned and the tectonic plates of capitalism shifted, a new breed of super-rich emerged. From factory owners to investors and industrial tycoons, these nouveau riche, often referred to as the “captains of industry,” found themselves at the helm of a wealth accumulation that was nothing short of astronomical. Living in grandiose mansions, attending opulent balls, and wielding an influence that reached far and wide, the nouveau riche stood in stark contrast to the masses.

On the flip side of this economic coin were the legions of factory workers, coal miners, and laborers who toiled for a pittance. As their employers reveled in their newfound fortunes, these workers endured the soul-crushing monotony of long working hours in squalid factories and returned home to equally dismal living quarters.

As the nouveau riche basked in their lavish banquets, there were those in the burgeoning industrial cities who could barely afford a morsel of food. Children worked in mines and factories to supplement the meager family income, and whole families huddled together in overcrowded and unsanitary tenements.

The disparity in living conditions served as a stark reminder of the growing wealth gap. The contrast between the dilapidated slums and the grand mansions and estates of the wealthy was a clear manifestation of the economic divide. The cities themselves became a patchwork of haves and have-nots, with distinct districts of affluence and poverty.

The chasm between the nouveau riche and the impoverished working class wasn’t just a material divide; it was a catalyst for social and political unrest. The glaring differences in quality of life, opportunity, and prospects between the two classes became a flashpoint for simmering discontent. This set the stage for social reform movements and political ideologies aimed at rectifying these inequities.

The Echoes of Industrial Change

In hindsight, it’s clear that the massive shift from individual craftsmanship to machine-driven mass production transformed the working class. Artisans, craftsmen, and farmers who once enjoyed a degree of autonomy found their roles and routines disrupted. Factory schedules replaced traditional work hours, machines dictated the pace of work, and workers became increasingly dependent on wages. These changes, from financial dependence to the emergence of workers’ rights, from wealth disparity to skill adaptation, have had a ripple effect, shaping societal upheaval and resonating deeply within working-class communities.

Looking back, however, a silver lining of the Industrial Revolution era was the groundwork it laid for the modern working class. The struggles and challenges faced by Industrial Revolution workers sparked advocacy for better working conditions, leading to a rise in worker solidarity and unity that would shape labor movements for generations to come. The modern working class has much to thank the Industrial Revolution for; from legal protections and rights to the structure of employment itself, the shadows of the past still shape the working world of today.