The Welsh Rebellions: How Princes Defied English Kings

The remarkable story of the Welsh rebellion is filled with bold acts of defiance and determination that echo through history. The Welsh have been an enduring source of inspiration for their tenacity and their fight for freedom.

Their rebellion’s history dates back to the Middle Ages, when numerous Welsh princes rose in open revolt against English rule. Each rebellion had its own cause and impact, but all were driven by the hope of safeguarding their homeland, culture, and autonomy. For example, Llywelyn the Great’s strategic matrimonial alliances, Owain Glyndŵr’s fiery campaigns, and Llywelyn ap Gruffudd’s unyielding spirit painted a vivid picture of resistance. Although the English Crown eventually solidified its control over Wales, the acts of defiance by Welsh kings and princes left an indelible mark on British history.

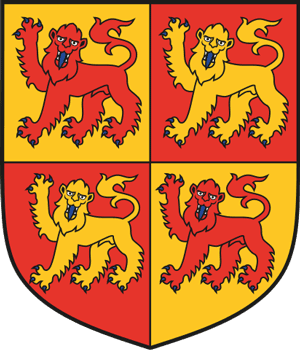

Llywelyn ap Iorwerth (Llywelyn the Great)

Jorellaf, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

| King of Gwynedd | |

|---|---|

| Reign | 1195–1240 |

| Predecessor | Dafydd ab Owain Gwynedd |

| Successor | Dafydd ap Llywelyn |

| Born | c. 1173 Dolwyddelan |

| Died | 11 April 1240 Aberconwy Abbey |

| Burial | Aberconwy Abbey |

| Spouse | Joan, Lady of Wales |

Llywelyn ap Iorwerth (1173–1240), known as Llywelyn the Great, was the most powerful prince in early thirteenth-century Wales. During his long reign, he established the most effective and sustained period of Welsh resistance to English rule since the Norman conquest. Llywelyn grew up in the turbulent 1180s and 1190s, a time of intense internal competition among the descendants of Prince Rhodri.

By around 1200, he had wrested sole control of Gwynedd from his rivals, and from this time on, he set out to rebuild the power and prestige of the principality. He aimed to preserve as much of Welsh independence and native rule as possible, and he did so by a gradual policy of defiance, a mixture of rebellion, opportunistic warfare, and diplomacy. Llywelyn was, however, not averse to fighting when circumstances were favorable, and between 1211 and 1216 he took advantage of English weakness to stage a successful rebellion.

He married the illegitimate daughter of King John in 1205, and his marriage served to check English aggression for several years. At this time, Llywelyn solidified his control over Gwynedd and began to assert his authority over the other Welsh rulers.

These efforts were dealt a blow by John’s actions after 1210, when the King began to take a more interventionist approach to the Marches and to demand greater submissiveness from Llywelyn. Llywelyn’s refusal led John to invade Gwynedd in 1211, after which Llywelyn was forced to offer a humiliating submission. The English king seized Gwynedd territory and Llywelyn’s daughters as hostages, and exacted a large annual tribute. However, this submission was a low point for Llywelyn, and it strengthened rather than ended his resistance to the English king.

In 1215, Llywelyn was able to turn this defiance into an all-out Welsh rebellion. John’s measures to impose his will on the Welsh princes had contributed to widespread opposition in England. In the summer of 1215, much of the English baronage rose in rebellion. Llywelyn took this opportunity to join forces with the English rebels, and he called for a general Welsh uprising. He moved quickly, and many of the English castles in Wales fell to Llywelyn’s forces. Many of the most important strongholds were taken in the south of Wales and along the Marches.

Once in control, Llywelyn isolated the garrisons with raids and sieges, and avoided open battles. English communications were cut, and their ability to concentrate forces was significantly reduced. Llywelyn demonstrated a firm command of mountain warfare, taking advantage of narrow passes to ambush the English and starve them into submission. These successes saw a further erosion of English power in Wales, and by the end of the year, the rebellion was in full swing.

This success allowed Llywelyn to establish his overlordship over the other Welsh rulers. In 1216, Llywelyn held a council of Welsh rulers at Aberdyfi. Most of the rulers were present, and many of them paid homage to Llywelyn as their overlord. It was a symbolic step, but one that united most of Wales and showed that English authority in Wales could be overcome by armed resistance. Llywelyn was neither an opportunist nor was he reacting to the pressures that England was exerting. He had begun to push back against English power and control, and he was leading an effective Welsh rebellion against it.

Llywelyn made the best of this opportunity and quickly turned it to diplomatic advantage. King John had died in 1216, and the new king, Henry III, was less willing to acquiesce to Llywelyn’s demands than his predecessor. Despite the threats he had received in 1211, Llywelyn submitted to the young king but soon used the rebellion as an opportunity for negotiation.

He met the English king, and the Treaty of Worcester in 1218 recognized Llywelyn as the first among equals among the Welsh rulers, with power over Gwynedd and most of Powys. While he submitted himself and his lands to the English Crown, Llywelyn remained independent for the most part and preserved the independence he had gained by limited military action and political maneuvering.

In later years, Llywelyn maintained his resistance to England and would fight on a limited scale when provoked to preserve this independence. During Henry III’s reign, a period of weak royal government in the Marches, Llywelyn was quick to respond when the Crown began to assert its authority more forcefully. He supported his Welsh allies and correspondents, and when war did come, he proved a thorn in the side of the English forces.

Llywelyn built and repaired castles, reoccupied and controlled lands, and kept up pressure on the Marcher Lords where he could. When Henry’s interventionism ended with the appointment of Robert of Gloucester as Justice, relations were more peaceful. But even though they were not in open rebellion, Llywelyn and Dafydd used war on a limited scale to resist English control of their lands in the south of Wales, north of the Dee. This limited war, combined with periods of peace, would characterize Welsh-English relations until Llywelyn died in 1240. Llywelyn the Great was the most powerful Welsh ruler of the early thirteenth century, and he spent much of his life using rebellion, diplomacy, and war to keep English power at bay.

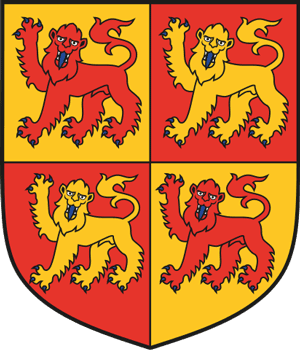

Dafydd ap Llywelyn

Jorellaf, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

| King of Gwynedd | |

|---|---|

| Reign | 1240–1246 |

| Predecessor | Llywelyn ab Iorwerth |

| Successor | Llywelyn ap Gruffudd |

| Born | March 1212 Castell Hen Blas, Coleshill, Bagillt, Flintshire, Wales |

| Died | 25 February 1246 (aged 33) Abergwyngregyn |

| Burial | Aberconwy Abbey |

| Spouse | Isabella de Braose |

Dafydd, son of Llywelyn the Great, born circa 1212, became Prince of Gwynedd after his father died in 1240 and found himself embroiled in a conflict with King Henry III of England, who sought to reduce the Welsh autonomy established by his father. Unlike his father, who skillfully balanced diplomacy and warfare, Dafydd was more reliant on armed resistance to counter English aggression.

Dafydd is most known for his surprise attack on Mold Castle in 1241. Mold Castle was an important English stronghold in North Wales, and its capture was a significant symbolic and strategic victory for the Welsh rebellion. The assault weakened the English presence in North Wales and showcased Dafydd’s willingness to employ direct military action against English outposts. The victory, however, was short-lived. In response, Henry III launched a large-scale military expedition against Dafydd, leading to the young prince’s submission at the Treaty of Gwerneigron in 1241. As part of the treaty, Dafydd was forced to surrender key territories and hostages to the English crown, marking an early defeat in his resistance against Henry III’s influence.

The reign of Dafydd ap Llywelyn saw the renewal of the Welsh rebellion in 1244, as he sought to expand his influence and resist the English crown once again. This time, Dafydd received the support of other Welsh lords who were disillusioned by Henry III’s interference in Welsh affairs. One of his most notable actions during this period was the siege of Dyserth Castle. Dyserth Castle was a strategically located English stronghold in northeastern Wales, and its capture was crucial for Dafydd’s campaign.

Although the siege was ultimately unsuccessful, Dafydd’s efforts against the castle marked a period of intensified guerrilla warfare and regional uprisings that significantly disrupted English control in Wales. The renewed campaign of 1244 underscored Dafydd’s determination to reverse the territorial and political losses he suffered after the Treaty of Gwerneigron and to challenge Henry III’s authority directly.

In 1245, Dafydd’s forces clashed with English troops at the Battle of Montgomery, a significant encounter fought near the border. The battle was a protracted and bloody engagement, with Dafydd’s forces initially successfully holding their positions against the English. However, the tide turned as the English managed to reinforce their army, and the Welsh troops suffered casualties. The Battle of Montgomery was significant, marking a turning point for Dafydd, as he subsequently lost his territorial gains and failed to secure additional alliances. Montgomery’s failure heralded the decline of his military campaign and the eventual need to adopt a different strategy.

Dafydd ap Llywelyn died suddenly in 1246 under mysterious circumstances. His unexpected death had significant consequences for the Welsh rebellion, leaving Gwynedd politically unstable and vulnerable to renewed English intervention. The power vacuum created by his death led to internal strife among the Welsh princes, further weakening the collective resistance against the English crown. Despite these challenges, Dafydd’s actions and defiance against Henry III inspired future generations of Welsh leaders. Notably, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, who emerged as a prominent figure in the later stages of the Welsh struggle for independence, considered Dafydd one of his direct predecessors and was influenced by his legacy.

Dafydd ap Llywelyn’s role in the Welsh rebellion is marked by his efforts to maintain his father’s hard-won independence against Henry III’s encroachments. His actions, including the successful but temporary capture of Mold Castle and the subsequent military campaigns of 1244, reflect a ruler forced to rely more on military resistance than on his father’s diplomatic acumen. Dafydd’s reign illustrates the challenges of maintaining internal unity and mounting an effective long-term resistance against a more powerful adversary. Despite his ultimate defeat and mysterious death, Dafydd’s legacy lived on in the continued struggle for Welsh autonomy and the inspiration he provided to future leaders.

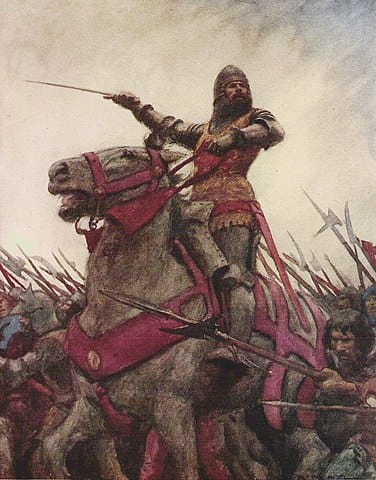

Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (Llywelyn the Last)

Jorellaf, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

| King of Gwynedd | |

|---|---|

| Reign | 1246–1282 |

| Predecessor | Dafydd ap Llywelyn |

| Successor | Dafydd ap Gruffudd |

| Prince of Wales | |

| Reign | 1267 – 1282 |

| Predecessor | Vacant |

| Successor | Dafydd ap Gruffudd |

| Born | c. 1223 Gwynedd |

| Died | 11 December 1282 Cilmeri |

| Spouse | Eleanor de Montfort |

Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, commonly known as Llywelyn the Last, was the last native Prince of Wales and a pivotal figure in the history of the Welsh rebellion. Born around 1223, he became a symbol of Welsh resistance against English rule and continued his father’s and grandfather’s dream of an independent Wales. Llywelyn ap Gruffudd inherited the title from his brother Dafydd and expanded his authority over most of Wales. Significant victories characterized his reign, but also by crushing defeats, leading to the eventual end of native Welsh rule under the reign of King Edward I of England.

The Welsh rebellion of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd is notable for its significant triumph in 1256, in which he sought to regain the Perfeddwlad (Four Cantrefs) from English rule. The success of this campaign solidified his position as the dominant power in North Wales, and from then on, he controlled most of Wales. This victory was a critical moment in the history of the Welsh rebellion, as it allowed Llywelyn to expand his power and influence, and it is seen as the high point of the native Welsh resistance. The Welsh lords rallied behind Llywelyn as their leader, and he was declared Prince of Wales in 1258. This title was formally recognized in the Treaty of Montgomery in 1267.

After this period, the relationship between Llywelyn ap Gruffudd and Edward I of England deteriorated. In 1277, Edward launched a campaign against Llywelyn, who was forced to submit to the king’s demand for homage and tribute. The Welsh suffered a crushing defeat at Deganwy, and Llywelyn was forced to sign the Treaty of Aberconwy, which resulted in him losing most of his power and land.

The defeat at Deganwy was a critical turning point in the history of the Welsh rebellion, as it effectively marked the end of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd’s power and the beginning of the end for the native Welsh rule. It is considered a decisive victory for Edward I and the English Crown and marked the start of a period of English domination over Wales.

In 1282, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd renewed the Welsh rebellion, taking advantage of growing unrest among his subjects. The campaign began with some early successes, but the turning point came in December 1282 at the Battle of Orewin Bridge. Llywelyn was killed in the battle, and with his death, the Welsh rebellion effectively ended. The Battle of Orewin Bridge is seen as a critical moment in the history of the Welsh rebellion, as it marked the end of native Welsh rule. The defeat at Orewin Bridge was a complete and utter rout, and without Llywelyn ap Gruffudd to lead them, the Welsh resistance quickly collapsed.

The impact of the defeat at Orewin Bridge on the Welsh rebellion was significant. In 1283, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd’s brother, Dafydd ap Gruffudd, was captured and executed by the English. With the deaths of Llywelyn and Dafydd, the Welsh rebellion was effectively over, and Wales was firmly under English control. This had a lasting impact on Welsh identity and culture, as Llywelyn ap Gruffudd became a symbol of Welsh resistance and martyrdom. His legacy inspired future generations of Welsh rebels, most notably Owain Glyndŵr, who led a rebellion against English rule over a century later.

The life and achievements of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd reflected the history of the Welsh struggle for independence. His victories showed what could be achieved with a united Wales, while his defeats and eventual death demonstrated the futility of resisting the might of the English Crown. The Welsh rebellion of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd is a powerful symbol of Welsh identity and the enduring struggle for self-determination.

Dafydd ap Gruffudd

| Prince of Gwynedd | |

|---|---|

| Reign | 1246–1282 |

| Predecessor | Dafydd ap Llywelyn |

| Successor | Abolished |

| Prince of Wales | |

| Reign | 1282–1283 |

| Predecessor | Llywelyn ap Gruffudd |

| Successor | English title: Edward of Carnarvon (1301-1307) Welsh title: Owain Glyndwr (1400/15) |

| Born | 11 July 1238 Gwynedd, Wales |

| Died | 3 October 1283 (aged 45) Shrewsbury, England |

| Spouse | Elizabeth Ferrers |

Dafydd ap Gruffudd, the brother of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, was one of the more prominent figures in the final years of the Welsh rebellion against the English crown. A notorious turncoat who switched sides between the Welsh and English crowns, Dafydd even went so far as to attack his own brother before finally joining the resistance. Dafydd’s role as leader of the resistance movement is considered the last organized effort to maintain Welsh independence after Llywelyn died in 1282.

The resistance under Dafydd, though heroic, was not well received as it was an uphill battle against a powerful and vengeful opponent. After his eventual capture and execution, Dafydd became known as the last Prince of Wales to have ever openly rebelled against the English Crown.

Dafydd’s initial entry into the fray as a leader began as a co-ruler along with his brother, Llywelyn. However, they were not always completely united and had some significant disputes. Following the death of Llywelyn at the Battle of Orewin Bridge in 1282, Dafydd became the de facto leader of the Welsh rebellion and rallied what was left of his forces to make a stand and carry out defensive operations. One of the more notable victories for Dafydd was the successful defense of Dolbadarn Castle. This victory was significant because it gave Dafydd and his forces a temporary stronghold and a foothold against the advancing English forces.

The significance of this victory cannot be understated, as it bought Dafydd some time and helped slow Edward I’s army. The respite Dolbadarn provided allowed Dafydd to regroup and reorganize his forces in the more northern regions of Wales while the English army prepared for another push forward. However, this was a reprieve, as the English recovered and returned in even greater force.

Another major loss for Dafydd and the Welsh forces was the fall of Castell y Bere in 1283. Located in the strategic region of Gwynedd, the castle was a key defensive position for the Welsh but fell after a prolonged English siege. The importance of Castell y Bere’s fall cannot be understated, as it signaled the fall of key Welsh strongholds and left Dafydd with little to which he could retreat.

The loss of this castle was not only a significant blow to the material resources available to the Welsh forces, but it also hit morale hard. With Edward I’s forces continuing their campaign with greater force and coordination, it became clear that Dafydd and his remaining forces were no match.

The final defeat and capture of Dafydd was when he was betrayed and ultimately captured near Bera Mountain in June of 1283 by his local allies. The defeat was significant because it ended the Welsh rebellion for good, as Dafydd was the last native Welsh leader able and willing to continue the fight. After his capture, he was taken to Shrewsbury, where he was hanged, drawn, and quartered. Dafydd’s execution was significant because it was the final nail in the coffin for the Welsh rebellion and represented the end of an era for Wales.

The implications of his death were far-reaching, as it not only ended the Welsh rebellion but also signaled the end of Welsh independence, as Wales was now firmly under the control of the English crown and legal system.

Dafydd’s role in the Welsh rebellion against the English crown is considered significant for many reasons. His involvement in the events, his rise to power, and his ultimate downfall all serve to add another chapter to Wales’ history of resistance against English domination. Though he was a lesser-known figure in Welsh history, Dafydd’s contributions to the rebellion and his role in Wales’ fight against the English crown are significant.

Owain Lawgoch (Owain ap Thomas ap Rhodri)

| Born | Owain ap Thomas ap Rhodri c.1330 Tatsfield, Surrey, England |

|---|---|

| Died | July 1378 The siege of Mortagne, France |

| Cause of death | Assassination |

| Resting place | Church of Saint Leger |

Owain Lawgoch (Owain ap Thomas ap Rhodri), also called Owain of the Red Hand, was a Welsh prince of the royal house of Gwynedd. He is an often-forgotten leader of the later Welsh rebellions against the English crown. Owain spent most of his life outside Wales, in France, as an exile. He rose in revolt against the English during the Hundred Years’ War, when Wales was used as a platform to strike at England, and he took the French side in the conflict. His battles were mainly outside Wales, but they were nonetheless part of the rebellion.

Owain’s most significant victory was in 1372 when he landed with a fleet of ships in Wales and undertook an invasion of the Principality. Owain commanded his own small army and successfully used the sea-borne nature of his campaign to attack English coastal towns. These raids were devastating for English coastal trade and defences, which were effectively pillaged by Owain’s ships. Owain’s victory was significant because he proved that an alliance with a foreign power, in this case the French, could achieve results outside of Wales itself. This invasion also showed that the dream of an independent Wales was not yet dead.

Owain was repulsed at Guernsey in 1372 by a numerically superior English force. The battle, which took place on Guernsey Island, ended in a decisive English victory as his own troops were too weak to successfully invade such a heavily fortified part of the English coastline. The invasion of Guernsey was a costly loss for Owain because it ended his campaign and limited his potential to launch further sea-borne operations into Wales itself. In the end, the repulse at Guernsey became a rallying call for the English, who grew more concerned about Owain’s potential to lead the Welsh rebellion.

Owain’s last campaign was his 1378 attempt to lead an invasion of Wales, with the help of the French. Owain was able to gather a force but never made it to Wales, as he was killed on the orders of King Edward III’s government in a pre-emptive assassination.

The English government had taken Owain’s raiding into their territory in 1372 as a personal affront and sent an agent to kill him, in the form of a Scottish spy called John Lamb. At the time, Owain was besieging Mortagne-sur-Gironde in Poitou. John Lamb gained Owain’s trust and was taken into service as his squire. In July of 1378, while out for a stroll with Lamb, Owain was stabbed and killed.

Owain’s death was a blow to the Welsh cause, as he was a good commander with both the experience and royal bloodline necessary to lead the Welsh.

Owain Lawgoch remains an iconic figure in Welsh history, being one of the most prominent exiled leaders of Welsh rebellion during this period. Owain differed from earlier leaders in that he was willing to make alliances with foreign powers, such as France and Spain. He became a symbol of Welsh nationalism and an inspiration to future leaders such as Owain Glyndŵr.

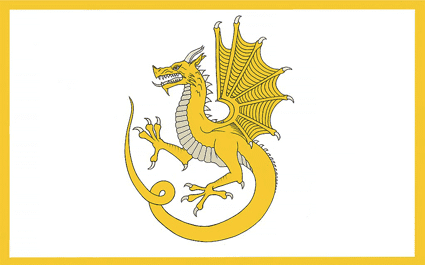

Owain Glyndŵr (Owen Glendower)

| Baron of Glyndyfrdwy, and Lord of Cynllaith Owain | |

|---|---|

| Reign | c. 1370-1400 |

| Predecessor | Lord Gruffydd Fychan II |

| Successor | Abolished |

| Prince of Wales | |

| Reign | 1400–1415 |

| Predecessor | Welsh: Dafydd ap Gruffydd (1282-1283) English: Henry of Monmouth (1399–1400) |

| Successor | Welsh: Vacant English: Edward of Westminster (1453–1471) |

| Born | Owain ap Gruffydd c. 1354 Sycharth, Wales |

| Died | 20 September 1415 (aged 60–61) |

| Burial | 21 September 1415 (unknown location) |

| Spouse | Margaret Hanmer |

The most significant rebellion in Welsh history, both in terms of its geographical reach and in its enduring symbolic legacy, is that led by Owain Glyndŵr (or Owen Glendower, in English). Glyndŵr was a Welsh nobleman born around 1359, believed to be descended from ancient Welsh royal dynasties. Starting in 1400, Glyndŵr began an armed revolt against English rule in Wales.

His goal was to establish a fully independent Welsh state with its own parliament and national church. Glyndŵr’s rebellion stands apart from previous uprisings due to its international scope (Glyndŵr forged alliances with France) and the size of the areas involved. In these respects, it was the most significant challenge to English power in Wales since the 13th century.

In 1401, Glyndŵr and his small force of Welsh infantry were victorious against a much larger English army at the Battle of Hyddgen. The battle was a pivotal moment in the Welsh rebellion, providing a substantial morale boost to the Welsh cause. The victory at Hyddgen proved to both Welsh nobles and commoners that the English could be defeated. Glyndŵr thus mobilized support for his rebellion across large swathes of central and northern Wales.

The battle also demonstrated the effectiveness of Welsh guerrilla tactics and the difficulties the English faced in suppressing the uprising with conventional military means. In the wake of Hyddgen, many regions in Wales declared their support for Glyndŵr and his vision of a free Wales, making it a truly national rebellion.

In 1402, Glyndŵr’s rebel forces defeated an English army twice its size at the Battle of Pilleth. The battle was significant as it further consolidated Glyndŵr’s position in Wales and enabled him to ally with the powerful Mortimer family through the marriage of his ally Sir Edmund Mortimer to Glyndŵr’s daughter. The victory at Pilleth also inspired further support for the Welsh cause among those who had been undecided or on the fence. In addition, the battle allowed Glyndŵr to gain a firm grip on the central and northern regions of Wales. Pilleth thus served to set up Glyndŵr’s dream of a unified Welsh government to displace the English administration.

The turning point in Glyndŵr’s rebellion came in 1405 at the Battle of Pwll Melyn, where an English force inflicted a heavy defeat on his troops. The battle was a crucial moment in the conflict as it resulted in the deaths of many of Glyndŵr’s key supporters, including his son Gruffudd.

As a result, the Welsh rebellion’s momentum was lost, and Glyndŵr was forced to retreat to the mountains. Pwll Melyn is a significant turning point, as after it, the Welsh rebellion gradually lost its way. Glyndŵr’s forces were significantly reduced in size and power, and he was never again able to launch large-scale attacks against English positions. Instead, the rebellion was reduced to small guerrilla units, which limited its effectiveness and appeal.

In the aftermath of Pwll Melyn, Glyndŵr was forced to adopt a more defensive posture, and the rebellion began to lose momentum. Glyndŵr’s defeat at Pwll Melyn had a significant impact on his ability to resist the English. With his forces depleted and the Welsh rebellion’s momentum lost, Glyndŵr was forced to take a more defensive approach and was unable to mount any significant attacks on English positions. As a result, Glyndŵr and his followers faded from view, with his last known appearance in 1415. Glyndŵr’s disappearance remains a mystery to this day, with no record of his capture or death.

In many ways, Glyndŵr’s final years are as shrouded in mystery as his death. He disappeared in 1415, and there is no record of his capture or death. This has led to speculation that he may have died in secret or lived out his days in hiding. Despite this, Glyndŵr’s final recorded years are of great interest and importance to historians and scholars.

He died, like so many before and after him, fighting for a free Wales, and, although he was not successful in his life, in his death, he became a myth, an icon, and a hero. The symbolic significance of the rebellion, even in its defeat, cannot be overstated. It left a lasting legacy of Welsh pride and nationalism, evident today.

The Legacy of the Welsh Rebellions

The narrative of the Welsh rebellions chronicles determination, resilience, and sacrifice. Successes ranging from Llywelyn the Great’s tactical victory at Aberconwy to Owain Glyndŵr’s significant victory at Pilleth showcase Welsh leaders’ ability to rally their forces and confront the English challenge. Defeats such as the capture of Castell y Bere by Dafydd ap Gruffudd or the critical losses of Owain Glyndŵr’s forces at Pwll Melyn were pivotal moments in the history of Welsh defiance. Every victory fueled hope, and every defeat served to shape future generations of leaders and warriors, ensuring that the struggle for Welsh autonomy persisted across centuries.

In the broader scope of history, the Welsh rebellions stand as a testament to the impact of failed struggles for independence. Despite the eventual loss, these efforts have indelibly shaped Welsh national identity and historical consciousness. The sacrifices made and the temporary autonomy gained became the stuff of national pride and are at the core of Welsh cultural memory.

The figures of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, Dafydd ap Gruffudd, and Owain Glyndŵr remain emblematic of the enduring Welsh spirit of resistance, their stories living on through literature, folklore, and nationalistic movements. While the Welsh rebellions did not secure lasting independence, they transformed it into a permanent ideal that continues to resonate in modern Wales, where the legacy of resistance is deeply ingrained in national identity.