The Time Ireland Invaded Canada: The 1866 Fenian Raids Explained

Yes, Ireland invaded Canada in 1866 (kind of). Here’s how: A loose coalition of Irish-American rebels known as the Fenian Brotherhood crossed the U.S. border into British Canada with rifles, combat experience, and an audacious aim. They intended to capture Canadian territory in order to extort Britain into granting Irish independence. The premise may sound like a novel, but it was very real (and, for a few days in June, a real risk of international crisis).

Fenians were mostly Irish who had fought for the Union in the American Civil War. Angry and anti-British, they took their aim north. Canada was weakly defended and still a British territory, making it an attractive target. The Fenian Raids that resulted are the only time in history that Ireland mounted a land invasion of Canada. The efforts were bold, but ill-conceived and chaotic. They failed, but had long-lasting implications for Canadian nationhood, and for the Irish independence movement.

Who Were the Fenians?

The Fenian Brotherhood was formed in the United States in 1858, a sister organization of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), founded by Irish nationalist John O’Mahony to provide financial and other support for a militant campaign in Ireland. The movement was strongest in the United States, where thousands of Irishmen had emigrated in the wake of the famine and subsequent repression in Ireland. Support for Irish independence was strong among Irish-Americans, many of whom considered leaving Ireland not as an act of surrender but as an opportunity to regroup and reassess.

The Irish-American community had been allowed to experience military conflict during the American Civil War, and tens of thousands of Irishmen had fought for the Union Army. The Civil War in America ended in 1865, leaving behind thousands of veterans armed with military training but no cause. The Fenian Brotherhood helped fill this void by giving these men a new direction: to continue the fight for Irish independence… not in Ireland, but against Britain itself.

The Fenians believed that the might of the British Empire could be forced into negotiations by military action in its colonial possessions. They considered a successful raid into British-ruled Canada and the subsequent occupation of various targets would be just the sort of embarrassment Britain would be forced to respond to. As one Fenian put it: “Canada is the hostage that will ransom Ireland.”

The ultimate aim was to force the British government to deal with the Irish Republican Brotherhood back in Ireland. Some Fenians believed that Britain would be plunged into an all out war over Canada; others felt even a limited campaign would be enough to send shockwaves around the world.

The tactics used by the Fenians were not universally popular within the wider Irish-American community; some considered them reckless and liable to cause an international diplomatic incident, while others felt they were the only option left after years of petitions and peaceful protests. Despite this, the Brotherhood began to raise money and resources for a militia, which it would lead into Canada, in what would be a brief but significant cross-border conflict.

The Political Context

The aftermath of the Civil War had left America militarized but divided. The nation focused on Reconstruction, but many of the Irish-American veterans who returned home looked not to America but to the unfinished revolution in Ireland. Their Civil War experience had created a new, battle-hardened generation of Irish-American activists—seasoned and determined to contribute to the cause of Irish freedom.

No. 1. Irish Volunteers, Colonel Benjamin Clinton Ferris, 9th Regiment;

No. 2. Napper Tandy Light Artillery, Captain John Fay, 70th Regiment;

No. 3. Montgomery Guard, Captain Thomas Murphy, 11th Regiment;

No. 4. Brigade Lancers, Captain Clancy, 11th Regiment:

No. 5. Irish Dragoons, Captain Kerrigan, 9th Regiment.

In Ireland and throughout the Irish diaspora, nationalist sentiment was swelling. In Ireland itself, resentment over evictions, famine, and political repression had inspired new waves of resistance. For Irish Americans, however, the struggle was more than an abstract conflict. Memories of family, friends, and communities back home shaped their worldview and commitment. In this context, attacking Canada was not just a tactical decision—it was a moral imperative.

American-British relations had not improved much during the 1860s. The British had officially remained neutral during the Civil War, but their shipbuilding industry had enabled the Confederacy, souring many in the Union. In this context, American federal officials were reluctant to take aggressive action against the Fenians. Though they did not officially support the raids, they were often slow to enforce laws or issue crackdowns, creating a gray area the Brotherhood exploited.

Federal ambiguity over Fenian raids worked in their favor. The Brotherhood’s members were overwhelmingly naturalized American citizens and veterans of the Civil War, making aggressive federal action politically unpalatable. As such, the Brotherhood was largely able to raise funds, ship weapons, and organize training openly in cities like Buffalo and New York, often hiding in plain sight as civic organizations or patriotic clubs.

British officials in Canada were also on edge. Intelligence gathering reported an increase in Fenian recruitment and arms stockpiling near the border. Canada’s defenses were scattered and underprepared, and local officials feared an imminent attack was likely. By early 1866, the tensions on the border were reaching a boiling point, and the Fenians were ready to strike.

Planning the Invasion

The Fenian Brotherhood’s attack on British Canada was as audacious as it was undisciplined. The leadership was divided between those who advocated a symbolic raid and those who envisioned a full-scale invasion. Several potential invasion sites along the U.S.-Canada border were identified, but a lack of coordination and insufficient resources hindered their development. Despite the internal disarray, the rank-and-file Fenians were enthusiastic. They believed that they could deal a decisive blow to the British Empire—or at least force a response from it through sheer boldness.

Canada was targeted not because it was the ultimate prize, but because it was vulnerable and had a British connection. It was close, unlike Ireland, and did not require an ocean voyage to reach. Its long and sparsely guarded border with the United States made it vulnerable, especially given the post-Civil War drawdowns of British forces. But more than that, Canada represented a part of the empire that the Fenians believed could be quickly seized and used as a means of leverage. It was, in their minds, a shortcut to Irish freedom.

The Fenians began mobilizing in the winter of 1865–66. In Buffalo, Cleveland, and New York, the Brotherhood held rallies, raised funds, and stockpiled weapons. Rifles, ammunition, and supplies were discreetly shipped to key border towns, and volunteer militias drilled in public parks or in private. Many of the men had fought in Union blue just months before, and they were eager to retake the field—this time under the green flag of Irish freedom.

The Brotherhood claimed to have tens of thousands of members ready and willing to fight, but in reality, far fewer were equipped or organized for military action. Nevertheless, their determination was unwavering. Letters and speeches from the period show a passionate belief that success in Canada would not only shake the British but also galvanize Irish nationalists at home. “We strike not at Canada,” wrote one Fenian, “but through Canada—at the heart of England’s pride and power.”

While some U.S. officials looked the other way as the preparations grew, others became increasingly alarmed. Border towns were abuzz with rumors of war, and British agents reported increasing unrest. But the Fenians pressed on, convinced that time and opportunity were on their side. By the end of the spring of 1866, the Brotherhood’s plans were well underway. The only question that remained was whether the dream of Irish freedom could withstand its first real test on Canadian soil.

The 1866 Raids Begin

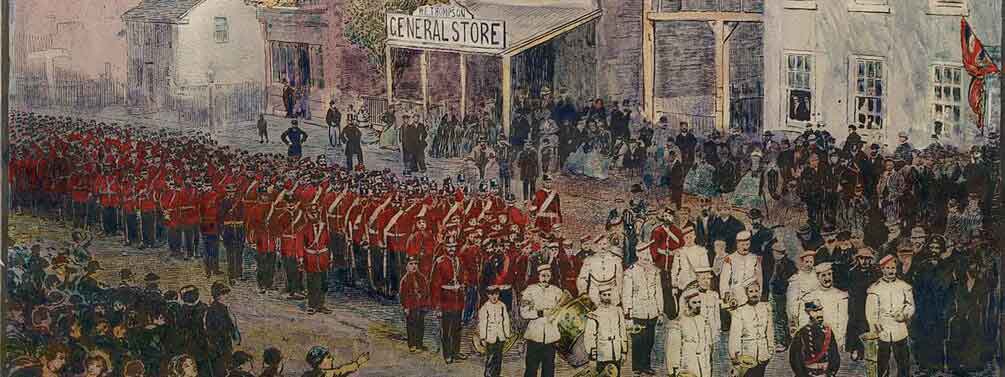

In the early morning hours of June 1, 1866, a ragtag army of approximately 800 Fenian insurgents crossed the Niagara River from Buffalo, New York, into Ontario. The Fenians, under the leadership of Colonel John O’Neill, a former Union cavalry officer, quickly overran the town of Fort Erie in a matter of hours. The crossing of the Niagara was rapid and virtually unchallenged, a symbolic first that heralded a new era of Fenian Raids and represented the first foray into Canada by Irish-American troops.

On the morning of June 1, O’Neill’s men advanced into the countryside, burning telegraph poles and confiscating supplies as they went. By mid-morning on 2 June, they had clashed with two Canadian militia units just outside the small village of Ridgeway. Several skirmishes broke out between the units, a conflict that would come to be known as the Battle of Ridgeway. In all, it was one of the rare times when an organized Canadian fighting force took the field on Canadian soil before Confederation. The Canadian troops, primarily composed of inexperienced militia, were poorly organized and woefully under-supplied with ammunition. Many others were armed with obsolete weapons.

For their part, the Fenians proved to be far more seasoned and cohesive on the battlefield. Fenian invader mobility outmatched the Canadian defense. Militia confusion and subsequent retreat resulted in an unequivocal tactical victory for O’Neill’s men. It was to be a great morale victory for the Brotherhood as a whole, as it offered a proud example of the Fenians being able to stand up to the might of imperial arms.

The ramifications of the conflict, however, were not all so encouraging. Reaction on both sides of the border was swift and at times mixed. In Canada, there was fear and outrage. Newspapers called for immediate improvements to border defense, and public opinion was galvanized into a call for greater national unity, helping to solidify public support for the Canadian Confederation the following year. In the United States, the government disavowed any involvement with the Brotherhood, but secretly rejoiced in the growing political excitement among Irish Americans. What had begun as a bold military adventure had turned into a diplomatic balancing act with potentially disastrous repercussions.

The Fenian Rapid Collapse

Despite their early success at Ridgeway, the Fenian raids quickly unraveled. A lack of centralized leadership and poor coordination among regional Fenian cells undermined any chance of a sustained offensive. Multiple invasion points had been proposed along the U.S.-Canada border, from Vermont to New York, but miscommunication and conflicting orders left many groups idle or disorganized. Some forces never mobilized at all, while others arrived too late to support the initial incursion into Ontario.

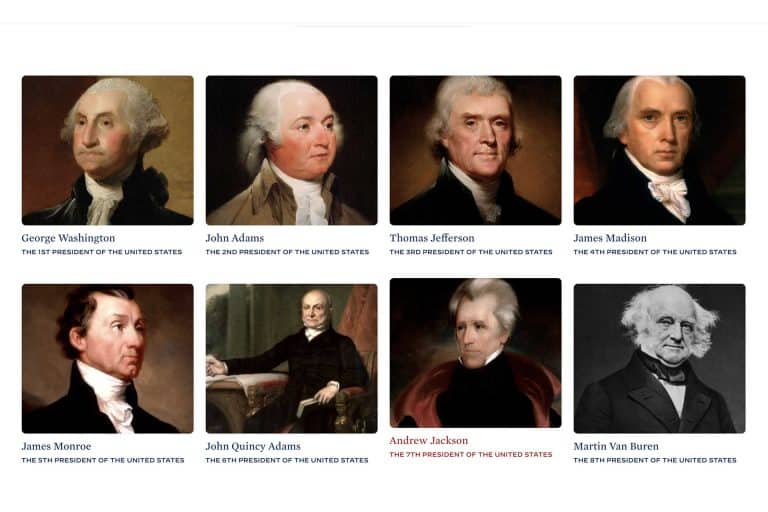

Meanwhile, the U.S. government, initially passive, shifted its stance as pressure mounted from British diplomats and Canadian officials. With the potential for international conflict growing, American authorities began arresting Fenian leaders, seizing weapons, and blockading further crossings. The same government that had turned a blind eye to the Brotherhood’s preparations now moved decisively to prevent escalation. President Andrew Johnson, eager to avoid diplomatic fallout, made it clear that the raids would not receive official support.

As federal agents tightened their grip, morale within the Fenian ranks faltered. Volunteer fighters, many of whom had expected a swift and symbolic victory, found themselves without supplies, reinforcements, or clear direction. Realizing they were now on their own, most Fenian units retreated across the border. Some surrendered outright; U.S. troops detained others upon re-entry. Within days, the Brotherhood’s bold campaign had collapsed under the weight of its disarray.

In total, hundreds of Fenians were arrested, although most were released within a few months. The Brotherhood’s leadership splintered as accusations flew and support waned. John O’Neill, who had led the Ridgeway victory, became a divisive figure—praised by some as a hero, blamed by others for strategic blunders. Without a unified vision or sustained public backing, the Brotherhood’s military momentum evaporated.

The raids had proven that the Fenians could mobilize quickly and fight effectively, but they also exposed deep flaws in their organization and strategy. What began as a defiant strike against imperial power ended in retreat, legal consequences, and fractured leadership. By the summer of 1866, the Fenian military threat to Canada had been extinguished, and the dream of forcing Britain’s hand through armed action on North American soil was slipping away.

Impact and Legacy

Although the Fenians’ success at Ridgeway was an early surprise, it did not take long for their plans to collapse. The decentralized nature of the Brotherhood and the poor coordination between the various regional Fenian groups undermined any chance of a large-scale Fenian invasion of Canada after Ridgeway.

The fact that several sites for the invasion of Canada had been chosen along the border between Vermont and New York, rather than sticking with just a single location, did not help coordination between the Fenians either, as miscommunication and contradictory orders left many Fenian groups waiting idly at one area or the other, or moving between the two without much of a clear plan. Some Fenian groups did not move at all, while others arrived too late to support the invasion of Ontario.

The United States government’s hands-off approach to the Brotherhood also began to change, as pressure from British diplomats and Canadian officials increased and the risk of a larger international conflict rose, American authorities began to arrest Fenian leaders, seize Fenian weapons, and blockade the border crossings on the Canadian-American border. The same government that was not doing anything about the Brotherhood building up an army along the Canadian-American border was now doing everything it could to ensure that the situation did not get out of hand. The threat of American diplomatic and legal action against the Brotherhood was enough to convince the headstrong President Andrew Johnson that he could not officially support the Fenian raids.

As U.S. federal agents began rounding up Fenian leaders and making arrests, morale in the Fenian ranks also began to wane. With volunteer Fenian fighters in the United States being left without food, supplies, reinforcements, or instructions, there was a realization that the Americans were no longer going to support the raids. They were instead on their own, forcing most of the Fenian units to retreat to the United States, with some groups simply surrendering to Canadian forces. In contrast, U.S. troops arrested others upon returning to the U.S. A bold move by the Brotherhood was over within days.

Hundreds of Fenians were arrested, and mutual accusations shattered the Fenian Brotherhood leadership. Most Fenians were released after a few months. The Brotherhood was no longer in a position to present a united front. John O’Neill, in particular, was a polarizing figure in the aftermath of the Fenian raids on Canada. While O’Neill had been at the helm of the Fenian forces that routed the Canadians at Ridgeway and many Fenians recognized him as a hero for doing so, he was also blamed by other Fenians for the failure of the Fenian raids on Canada. With no cohesive plan or political and public support, the Brotherhood lost its military momentum.

The Fenian raids had demonstrated that they could organize an army relatively quickly and fight capably in battle; however, the raids had also revealed significant flaws in the Fenian organizational and strategic approach. The Fenian raids had begun as an act of defiance against the still-influential British imperial power. They had ended in retreat, arrest, legal action, and internal strife among Fenian leaders. By the summer of 1866, the Fenian military threat to Canada was over, and Fenian hopes of forcing Britain’s hand through action on North American soil were in serious trouble.

A Forgotten Chapter with Lasting Echoes

It is hard to imagine a more unlikely event than the Fenian Raids of 1866, when Irish-American radicals used their experience in the US Civil War to invade Canada in the hope of securing the British withdrawal from Ireland. Even though they were only a temporary incursion, the fact that hundreds of idealists crossed the border with weapons in their hands, marching and encamping on British soil, is evidence of the international nature of the Irish nationalist struggle.

The Fenian raids have been largely forgotten by Canadians and by Irish people alike. Still, they stand out as a key moment in the history of the world’s first diaspora movement, and an extraordinary instance of the violent interaction between the First and Second British Empires, as the former empire used the resources of the latter to attack it, an attack which failed to liberate Ireland but which shook the mightiest empire the world had yet seen and brought forward the emergence of a new nation, Canada.

![[Video] Phrase Origins: Mad as a Hatter](https://historychronicler.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Screenshot-2025-09-30-at-8.00.59-PM-768x512.jpg)